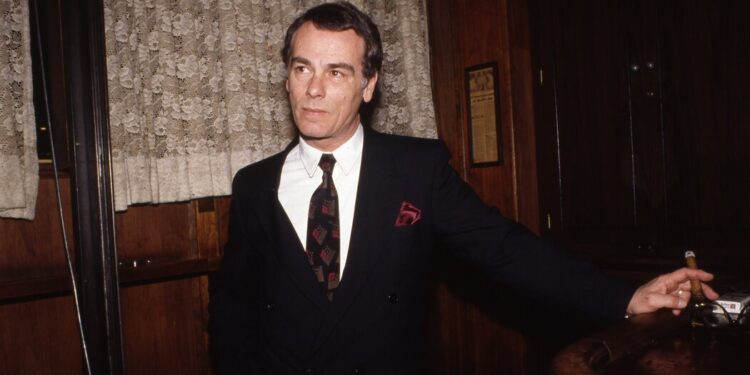

Dean Stockwell, who began his seven-decade acting career as a child in the 1940s and later had key roles in films including “A Long Day’s Journey Into Night” in 1962 and “Blue Velvet” in 1986, while also making his mark in television, most notably as the cigar-smoking Al Calavicci on the hit science fiction series “Quantum Leap,” died on Sunday. He was 85.

His death was confirmed by Jay Schwartz, a family spokesman, who did not say where Mr. Stockwell died or specify a cause.

Mr. Stockwell had a hot-and-cold relationship with acting that caused him to leave show business for years at a time. But he nonetheless amassed more than 200 film and television acting credits from 1945 to 2015, as well as occasional stage roles.

As a child he appeared alongside some of the biggest stars of the day, including Gene Kelly and Frank Sinatra in “Anchors Aweigh” in 1945, when he was not yet 10. But while many child stars don’t make the transition to adult careers, Mr. Stockwell was blessed with angular, rugged good looks as a young man and a distinguished maturity later, attributes that made him suitable for all sorts of roles.

Several times Mr. Stockwell lost interest in the profession that he had been all but born into, escaping to work on railroads and in real estate and, in the 1960s, to immerse himself in the counterculture. He also enjoyed several career revivals, notably in the 1980s, when he was cast in career-defining roles in movies like Wim Wenders’s “Paris, Texas,” David Lynch’s “Dune” and “Blue Velvet” (as the menacing and eccentric henchman of a drug dealer played by Dennis Hopper), and Jonathan Demme’s “Married to the Mob,” in which his performance as a mob boss earned him an Academy Award nomination for best supporting actor.

As the son of actors — his father, Harry Stockwell, and his mother, Elizabeth Veronica, appeared onstage and in films together, and Harry Stockwell provided the voice of Prince Charming in Walt Disney’s “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” — Mr. Stockwell had little semblance of a typical childhood before he began acting.

He first appeared on Broadway in 1943, at age 7, in “The Innocent Voyage.” (His older brother, the actor Guy Stockwell, who died in 2002, was also in the cast.) He was recruited by a Hollywood talent scout, and his movie career began in 1945, when he appeared in “The Valley of Decision,” with Gregory Peck and Greer Garson, and in “Anchors Aweigh.”

Mr. Stockwell was immediately praised for his skill, winning a special award at the Golden Globes for “Gentleman’s Agreement” in 1947. Reviewing the movie “Kim” in 1950, Bosley Crowther of The New York Times praised his performance as “delightfully sturdy and sound,” adding, “Little Dean shows a real tenderness.” Other Times reviews of his performances as a child called his work “touching,” “commendable” and “cozy.”

Robert Dean Stockwell was born on March 5, 1936, in Los Angeles. His parents divorced when he was 6, and he spent most of his childhood with his mother and brother. He would later say that he looked up to directors and leading actors on the set as father figures.

He would appear in 19 films before he turned 16, at which point he quit acting for the first time. Withdrawn as a child, he took little pleasure in acting, seeing it as an obligation foisted upon him by others, he said in an interview with Turner Classic Movies in 1995.

“If it had been up to me, I would have been out of it by the time I was 10,” he said.

After graduating from high school at 16 — as a child actor, he received three hours of schooling while working — Mr. Stockwell realized he had little training to do anything else. He flitted from one odd job to the next before reluctantly returning to acting in 1956, when he was 20.

One of his biggest roles in his 20s was alongside Jason Robards, Katharine Hepburn and Ralph Richardson in the 1962 film version of Eugene O’Neill’s “Long Day’s Journey Into Night,” in which he played the younger son, Edmund Tyrone. He, Mr. Robards and Mr. Richardson shared an acting award at the Cannes Film Festival.

Other notable roles in that period included “Compulsion” (1959), a fictionalized version of a well-known murder case, in which he and Bradford Dillman played the killers of a young boy; and “Sons and Lovers” (1960), based on the novel by D.H. Lawrence.

Later in the 1960s, Mr. Stockwell found comfort in the counterculture movement and the hippie ethos.

“My career was doing well, but I wasn’t getting anything out of it personally,” he told The Times in 1988. “What I was looking for I was finding in another place, which was in that revolution. The ’60s allowed me to live my childhood as an adult. That kind of freedom, imagination and creativity that arose all around was like a childhood to me.”

After a few years off, he returned to acting, only to learn that his time away had led Hollywood casting agents to forget him. For about a dozen frustrating years, he struggled to land roles, appearing in fringe films and performing in dinner theater.

“I even heard about a casting meeting where the producer said, ‘We need a Dean Stockwell type,’” he told The Times in 1988. “Meanwhile, I couldn’t even get arrested.”

He quit acting again in the early 1980s, moving to New Mexico to sell real estate. His next comeback would be his most successful, beginning a decade of his most critically acclaimed work.

In 1988, he was acclaimed, and Oscar-nominated, for his performance in “Married to the Mob.” The next year, he was cast in “Quantum Leap.”

That show, seen on NBC from 1989 to 1993, starred Scott Bakula as Sam Beckett, a scientist who, because of a botched time-travel experiment, spends his days and nights being thrown back in time to assume other people’s identities. Mr. Stockwell portrayed Adm. Al Calavicci, described by John J. O’Connor of The Times in a 1989 review as “Sam’s wiseguy colleague, who hangs around the edges of each episode, setting the scene and commenting on the action.” Mr. Stockwell, Mr. O’Connor wrote, was “Mr. Bakula’s indispensable co-star.”

Mr. Stockwell was nominated four times for an Emmy Award for best supporting actor in a drama series for his work on “Quantum Leap.” He never won an Emmy, but he did win a Golden Globe in 1990.

He is survived by his wife, Joy Stockwell, and two children, Austin and Sophie Stockwell.

In a 1987 interview with The Times, Mr. Stockwell said that his approach as an actor hadn’t changed since he was a child.

“I haven’t changed in the least,” he said. “My way of working is still the same as it was in the beginning: totally intuitive and instinctive.

“But as you live your life,” he added, “you compile so many millions of experiences and bits of information that you become a richer vessel as a person. You draw on more experience.”

Neil Genzlinger contributed reporting.

Discussion about this post