Future doctors are required to learn anatomy and much else. Lawyers must have a basic grasp of civil and criminal procedure and, in the United States, prove it by passing a bar exam. For professional artists, the path is less clear. Today, as the scholar Nicholas Houghton wrote in a 2016 paper on art school curriculums, “there are ever more things that could be taught without there being anything which has to be.” While particular skills — a mastery of perspective, say — may have been essential in some eras, in some places, artists now do anything and everything, from cooking food to social justice work to having specialists fabricate supersize sculptures for them and even, at least in the case of Sergio Muñoz Sarmiento, attending law school, as part of their practice.

Unsurprisingly, then, the academic side of the art world is just as varied. There are prestigious schools that dealers flock to in search of talent, and that offer M.F.A.s (at various price points) and even Ph.D.s to hone thinking and credential would-be teachers. There are also artist-run initiatives and a worldwide constellation of residencies that can serve as luxe getaways or back-to-nature boot camps. As with school programs, some come with generous stipends; others charge hefty fees. “There’s a whole industry around residencies,” says the artist and curator Michelle Grabner. She’s taught painting and drawing for years at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago while also helping to run an unorthodox residency at a place called the Poor Farm in rural Wisconsin that aims to see, she says, “How loose can it become before it is just a flophouse?” Every program “has different limitations,” she says, “but it’s a broad and beautiful playing field.”

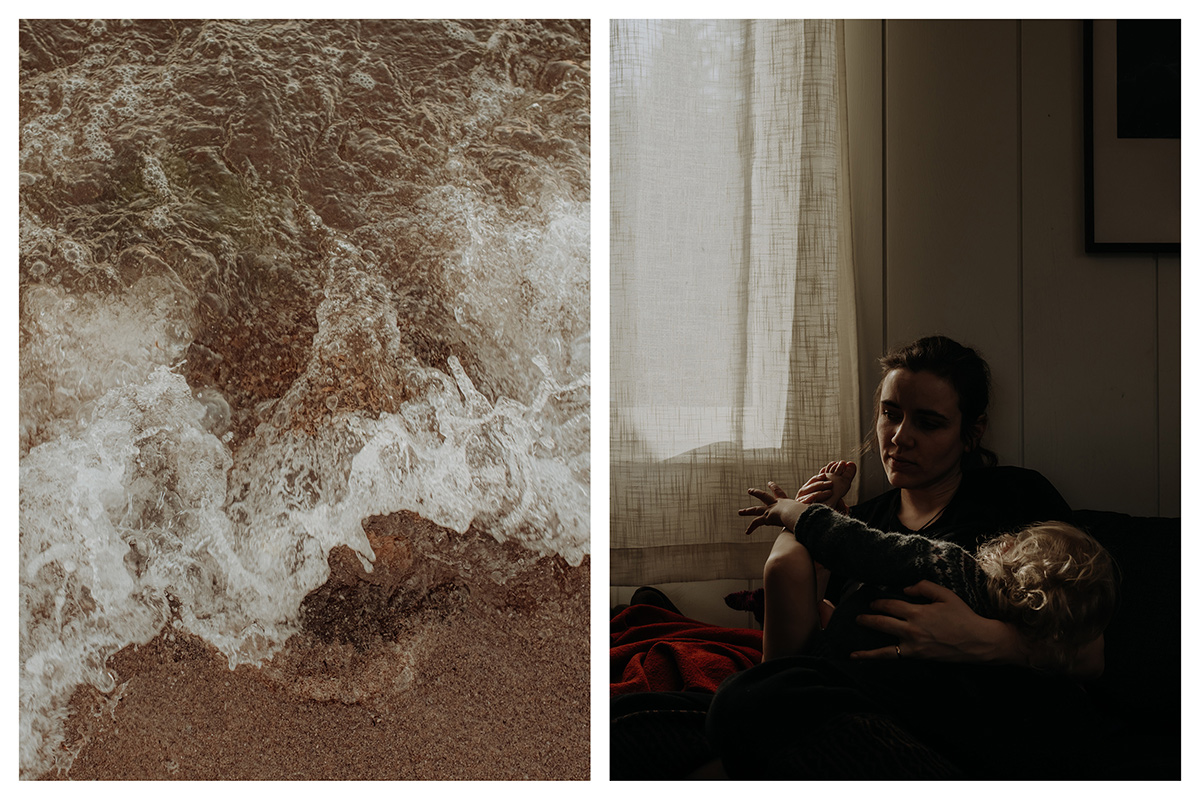

Below, T has compiled a brief overview of that playing field, highlighting some of the residencies and full-on art schools, both storied and recently founded, that are on the radar of New York art types, and for which — if an aspiring artist is in want of formal training (Jasper Johns, for one, has managed just fine with only a few semesters of college) or at least of some time to explore their practice — they might consider applying. The competition can be fierce, but the experiences can be transformative. Yashua Klos, who makes vivid collages that have graced many museum walls, attended the Skowhegan summer program in Maine in 2005 and, he says, “developed relationships there that have helped stabilize my career to this day.” The painter Heather Guertin, who was in residence at the Palazzo Monti in Brescia, Italy, in 2017, still recalls what she describes as the “heavenly 18th-century fresco on the ceiling” of her studio. “During my time there I was able to make a shift in my work from hard-edge forms to a more painterly expression,” Guertin says. “Without me even trying, all of the colors of the Renaissance made their way it into my paintings.”

Städelschule | Frankfurt

Frankfurt may not have the frenetic art scene of Berlin, but it is home to a deeply respected and highly exclusive art school. Of the hundreds who apply each year, the Städelschule accepts just a couple of dozen students. It traces its history back some 200 years (to a bequest left by an art-loving banker, Johann Friedrich Städel), but its curriculum has a contemporary and, to use the school’s own words, “emancipated form.” Over the course of 10 semesters spent in close dialogue with professors (sometimes in its famed Mensa cafeteria), students can take workshops in sound, cooking, life drawing and more — largely practical studies that are balanced with doses of art history and theory. It’s a method that seems to work. The school’s graduates include Danh Vo, Anne Imhof and Haegue Yang, who now teaches at the Städelschule (and serves as vice rector) alongside the curator Daniel Birnbaum and the art historian Isabelle Graw. Together, these and other marquee names associated with the institution form a rich network that wields power in countless kunsthalles and white cubes. It should also be noted that the per semester fee is a mere €375.50, or about $400 — low enough to make loan-burdened Americans weep.

Whitney Independent Study Program | New York

Started by New York’s Whitney Museum in 1968, the Independent Study Program (ISP) is a tripartite institution with tracks in critical studies, curatorial work and studio practice. Each year, the latter typically welcomes 15 artists, from undergraduates to M.F.A. holders, for nine months of serious (but grade-free) study with leading artists and scholars. At the ISP’s helm is Ron Clark, a former artist who helped establish the program. He’s made theory (Marxist, poststructuralist, feminist) the foundation of its curriculum; the alumni list includes Andrea Fraser, Gregg Bordowitz and LaToya Ruby Frazier. Certain cohorts are especially impressive in hindsight — 2002-03’s class included K8 Hardy, Alex Hubbard, Mai-Thu Perret and Ulrike Müller — and some participants return to lead the weekly seminar at the ISP’s heart. Tuition is $1,800, and assistance is available: all in all, a fairly affordable entree into the New York art world. There’s also a bonus incentive for future applicants. The family of Roy Lichtenstein (a former seminar leader) recently donated his Greenwich Village studio to the Whitney, which plans to make it the ISP’s headquarters in 2023, following a renovation by the Johnston Marklee firm.

Black Rock Senegal | Dakar, Senegal

Kehinde Wiley’s majestic portraits have become such a touchstone of contemporary art that its astonishing to remember he’s only 45. His works fill museum collections and, in 2018, he unveiled a portrait of President Obama sitting amid a sea of foliage. The next year, Wiley founded Black Rock Senegal, set in a palatial oceanfront venue in Dakar that includes living and working space for himself plus apartments and studios for three residents, who come for one to three months at a time. Eligibility isn’t limited to visual artists. (Alums include the writer-director Abbesi Akhamie and the musician turned painter and sculptor Curtis Talwst Santiago.) Wiley, who was born in Los Angeles and is now primarily based in New York, fell in love with Senegal on his first visit there in his late teens, right before he rocketed to fame, and with this program he aims to share the area with others. It is “also about being able to just spoil the artists and make them feel like they’re respected as thinkers and as part of the culture,” he told The New York Times in 2019. Considering that the compound, designed by the architect Abib Djenne, has a sauna, an infinity pool and a library, that meals are provided and that a language tutor is at the ready to teach English, French and Wolof, it’s a wonder residents ever agree to leave.

Cooper Union | New York

For more than 100 years, the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art offered undergraduates something extremely alluring: zero tuition. That ended in 2014, when the esteemed school of art, architecture and engineering began charging on account of financial difficulties, a move that outraged its faculty, student body and alums. Protests ensued. Still, with an 8 percent acceptance rate for the 2021-22 academic year, Cooper remains an attractive destination for its record of producing major talents (Avery Singer, Firelei Báez, Wangechi Mutu), its internationally renowned professors (Walid Raad, Lucy Raven, Coco Fusco) and its location in Manhattan’s East Village, a short stroll from numerous galleries. Half-tuition scholarships are provided these days, and — good news for parents of artsy youngsters who are already desperately socking away cash — the institution’s board said last year that it has been righting its balance sheet and is on track to do away with tuition once more by the end of the decade. The businessman, inventor and abolitionist Peter Cooper, who established the school in 1859 and believed that “education should be free as air and water,” would no doubt approve.

California Institute of the Arts | Santa Clarita, Calif.

Walt Disney died in 1966, four years before the multidisciplinary school he’d been working to build, following the 1961 merger of the Chouinard Art Institute and the Los Angeles Conservatory of Music, began welcoming students on a new campus just north of Los Angeles. Had he lived just a little longer, he would have seen CalArts, as the school is known, become a hotbed of avant-garde activity in the visual arts, with some early graduates quickly making their names in the buzzing New York art scene of the ’80s. Two of those names are David Salle (B.F.A., ’73; M.F.A., ’75) and Jack Goldstein (M.F.A., ’72), who, along with some of their associates, were christened the “CalArts Mafia.” And the school hasn’t stopped minting stars; recent alums include Kaari Upson (B.F.A., ’04; M.F.A., ’07) and Henry Taylor (B.F.A., ’95). The program combines hands-on learning and in-depth discourse: Michael Asher’s Post-Studio class, which ran for more than three decades, was known to stretch to 12 hours as students critiqued one another’s work. Today, the professors include critically lauded giants like Cauleen Smith, Sam Durant and Charles Gaines, and unlike in the ’70s, Los Angeles’s flourishing art world means that grads no longer need to head east after getting their degree.

Palazzo Monti | Brescia, Italy

Sure, you could head deep into the woods for your residency. That is a classic choice, promising few distractions. But if you are willing to be immersed in — and contend with — art history, Palazzo Monti might be a better one. It’s named for the 13th-century building appointed with 18th-century frescoes that it calls home in beautiful Brescia, a little over an hour east of Milan by car. Started in 2017 by Edoardo Monti, a collector and curator whose grandfather acquired the building in 1950, the initiative has so far hosted more than 170 artists, Somaya Critchlow and Kadar Brock among them. Up to three are there at a time, and they typically stay for a month. Each is asked to leave a work behind — hence the sturdy bookshelf by Davide Ronco and the floor-to-ceiling textile work by Bea Bonafini on site. The program makes some supplies available, and additional creative inspiration is on offer in the museum-rich city, and in nearby Padua, where Giotto’s Scrovegni Chapel frescoes, beloved by both John Ruskin and Marcel Proust, await.

Forge Project | Taghkanic, N.Y.

The youngest entry on this list, the Forge Project was started in 2021 by the philanthropist Becky Gochman and the erstwhile gallerist Zach Feuer to support Indigenous artists and pursue causes related to food access and land justice. Based in New York’s Hudson Valley (on unceded Muh-he-con-ne-ok land, as the organization notes), it acquires work by Indigenous artists that it loans to exhibitions, hosts programming and taps six people working in a wide variety of fields each year for its Forge Fellowship. Recipients get $25,000 in funding and stay for three weeks at Forge’s campus (with structures designed by Ai Weiwei), where they can conduct research and present their work, though there’s no requirement to complete any kind of project. “We recognize that what they might need most is time and space to think, to read, to spend time simply being on the land,” says Forge’s executive director and chief curator, Candice Hopkins (Carcross/Tagish First Nation). Only two cohorts have been named so far, but their members make for an impressive bunch. The 2021 group included Sky Hopinka (Ho-Chunk Nation/Pechanga Band of Luiseño Indians), who makes bewitching photographs and films and who became a juror for the 2022 edition, which featured Laura Ortman (White Mountain Apache), a multitasking musician who established the all-Native American Coast Orchestra group in 2008, and Sara Siestreem (Hanis Coos of the Confederated Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua and Siuslaw Indians), whose work includes printing and weaving. The community will grow again when the next group is announced in spring of 2023.

Skowhegan School of Painting & Sculpture | Maine

Some 350 acres — which are home to lakeside cottages, studios devoted to sculpture and fresco, a multimedia lab, and a more-than-14,000-volume library — are in store for the roughly 65 emerging artists selected for this intensive nine-week summer residency, which was created just after World War II. In 1946, Willard W. Cummings established the program on his family’s farm in Skowhegan, Maine, with his fellow artist Sidney Simon, whom he’d met in the Army’s War Art Unit, and two others. It’s been artist-run ever since. A board names five resident-faculty artists and five visiting-faculty artists each year, and they are joined by various visiting artists, all of whom offer lectures and studio visits. (Despite the traditional mediums in Skowhegan’s official title, these practitioners’ specialties run the gamut. This season’s faculty includes the inventive animator Kota Ezawa and Abigail DeVille, a venturesome installation artist and sculptor.) Temporary departures from the sylvan landscape for professional activities are prohibited, but the place has been known to have a hold on people. Attending in 1949, Alex Katz studied plein-air painting and, a few years later, bought a house in Maine that has been inspiring some of his most celebrated work ever since.

The Fabric Workshop and Museum Artists in Residence | Philadelphia

Artists looking to push their practice and create something strange and new have experts ready to assist them through the artist residency run by Philadelphia’s Fabric Workshop, which has specialized in producing and exhibiting work involving textiles and printing since its founding in 1977. The program is, alas, invitation-only, but its advisory committee welcomes artists at every point of their careers, generally for 18 to 24 months — an unusually long time for a residency — and an honorarium and production funds are included. The few lucky enough to be selected each year are able to work on ambitious projects that are eventually displayed at the museum. In 2013, Sarah Sze created faux boulders by printing images of rocks on Tyvek; in 1994, Chris Burden created 30 imposingly oversize Los Angeles Police Department uniforms, complete with a badge, baton and Beretta. Joining their ranks in the 2023-24 class will be Risa Puno, Borna Sammak and Jessica Campbell.

Pivô | São Paulo, Brazil

In the bustling São Paulo art scene, which has a long-running biennial and a major art fair, SP-Arte, the nonprofit arts organization Pivô is a standout player. Pivô’s space alone makes it notable: It occupies part of the Copan Building, a faded modernist giant of a residential structure designed by Oscar Niemeyer and completed in 1966. But it also has an exhibition program that has attracted sustained international attention (curators from abroad regularly swing by on visits to the city) and a well-connected residency called Pivô Research. During the residency’s first almost-decade in existence, north of 150 residents from Brazil and further afield have attended, Yná Kabe Rodríguez, Daniel Albuquerque and Matthew Lutz-Kinoy included. Up to nine artists take part in each of the three 12-week cycles Pivô hosts annually, and they receive studio space and a monthly stipend, meet with visiting curators and the art center’s curatorial team and develop new work.

The Studio Museum in Harlem’s Artists in Residence | New York

Every year, three artists of African or Afro-Latinx descent are selected for this lauded 11-month artists-in-residence (A.I.R.) program, which has been an integral component of the Studio Museum in Harlem since its founding in 1968. Some 150 artists have now participated and its list of alums — which includes David Hammons, Kerry James Marshall, Julie Mehretu and Titus Kaphar (all of whom went on to become MacArthur “genius” grant recipients), as well as Simone Leigh, who is representing the United States at the current Venice Biennale and recently took home the prestigious Golden Lion for creating the best work in the fair’s main show — “reads like a canon of a half-century of Black American art,” as the journalist Siddhartha Mitter put it in 2020. Beyond providing studios and mentorship, the Studio Museum gives $25,000 to each artist and puts on a group show of each class’s work that is always closely watched. Since the museum shuttered for construction in 2018, these exhibitions have been taking place at MoMA PS1 in Queens. But the Studio Museum’s David Adjaye-designed home is set to open in 2024 and will feature more than twice as much space for both exhibitions and the A.I.R. program.

The Poor Farm | Little Wolf, Wis.

The married artists Michelle Grabner and Brad Killam are apparently indefatigable. They maintain solo practices, teach in the academy (at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and the College of DuPage, respectively) and since 1999 have run a well-regarded exhibition space in a garage in suburban Oak Park, Illinois. (Naturally, it is called the Suburban.) Since 2008, they’ve also operated a multifarious arts center in what was once the Waupaca County Poor Farm, a home for the indigent built in 1876 in Little Wolf, Wisconsin. It presents exhibitions, is home to a publishing imprint, has its own beer (a pilsner by the artist John Riepenhoff with Milwaukee’s Company Brewing, proceeds from which benefit the center) — and contains 16 beds that allow it to host a residency called Living within the Play. Sometimes, whole university classes are in residence. At other times, it’s just random individuals or groups. (There is no official application; you just ask to come.) But while the premise is low-key, big things are afoot. This summer, the residency is setting up shop at the International Center for the Arts in Monte Castello di Vibio, Italy, north of Rome, and back at the farm, an exhibition called “Model Home,” with work by Mira Dayal, Félix González-Torres and Jonas Mekas, will open in August.

Discussion about this post