Here, briefly, is the situation: The West’s public lands are under attack. National monuments are at perpetual risk of being shrunk or repealed; development threatens our wildest places; and powerful ranchers seek to neuter land-management agencies. Some conservatives yearn to transfer public lands out of federal jurisdiction altogether.

This is both our West and the West of Bernard DeVoto, the mid-20th-century historian and conservationist whom Wallace Stegner once dubbed “the nation’s environmental conscience.” Compared to conservation’s other luminaries, DeVoto — crankier than Stegner, less poetic than Rachel Carson, not quite as quotable as Aldo Leopold — has largely fallen into obscurity. Although his Western histories won a Pulitzer Prize and a National Book Award, his most widely read work today is The Hour: A Cocktail Manifesto, a tongue-in-cheek celebration of American whiskey. Yet, as journalist Nate Schweber demonstrates in his timely new biography, This America of Ours, DeVoto was a legend in his own time whose influence endures today — “as important to conservation as Theodore Roosevelt and Gifford Pinchot.”

DeVoto grew up in Ogden, Utah. A pugnacious outdoorsman, he escaped his domineering father by heading east to study literature. While teaching at Northwestern University in 1922, DeVoto fell for Avis MacVicar, a superlative student who “had a way of speaking like the first lines of novels.” DeVoto dreamed of writing the great American novel himself, but environmental journalism beckoned, especially after a visit to Utah in 1925, when the DeVotos narrowly escaped a flash flood triggered by clear-cutting, overgrazing and erosion in the Wasatch Mountains. Outraged, DeVoto began writing magazine stories, edited by his brilliant wife, exposing the rapacious cattle, timber and dam-building interests despoiling the “plundered province” of the West. By 1952, his renown was such that Adlai Stevenson consulted him on the natural resources plank of the Democratic national platform.

DeVoto’s enemies were as powerful as his allies. He attacked both Joseph McCarthy, the scurrilous prosecutor of the Red Scare, and Patrick McCarran, a shamelessly corrupt Nevada senator who wanted to seize federal lands and sell them off to private interests. DeVoto shrewdly connected their seemingly unrelated activities. Any conservationist who cared about public lands, he observed, soon found himself under FBI investigation, including DeVoto himself, who warned in 1949, “We are dividing into the hunted and the hunters.”

Schweber’s skillful reporting here equals that of his subject. Drawing upon letters, FBI files and his own interviews, he unearths the horrific saga of Roald Peterson, a Forest Service rangeland specialist and DeVoto ally who was baselessly accused of Communism and fired. Peterson’s family was shattered, and two of his children committed suicide. Although DeVoto longed to cover the case, Peterson, fearful of further retaliation, asked him not to, leaving the writer “haunted by a guilt that he had not done enough to stop a tragedy.”

Not that DeVoto often censored himself. Much of the pleasure of This America is watching him wield his megaphone. Our modern news landscape is so atomized and polarized that the media often appears powerless; when Facebook’s algorithms funnel readers into news silos, it’s difficult for any story to gain traction. (Consider all the investigative reporting on Donald Trump’s fake charities in 2016, for instance, and how little impact it had on the election.) DeVoto, by contrast, wrote at a time when a Harper’s columnist could kill legislation with a few clacks of his typewriter. When McCarthy delivers a 1952 election night speech “concentrated mainly on DeVoto,” it’s a reminder of just how much politicians once feared journalists.

DeVoto attained his influence with much help from his spouse. Avis DeVoto’s role in her husband’s career has been largely overlooked, owing in part to her own reticence; when she recruited Stegner to write DeVoto’s biography, she insisted that she didn’t want “publicity of any kind.” Schweber describes a power couple who were equals in intellect, if not fame. Bernard may have won the Pulitzer, but it’s Avis’ witty, irreverent correspondence that provides much of This America’s texture. (“The cattle-raisers are screaming blue murder over this drop in the market,” she wrote after a collapse in beef prices burned Bernard’s adversaries, “and I can’t think of when I’ve been more pleased.”) A shrewd talent scout, she discovered Julia Child; after Mastering the Art of French Cooking was published, Child wrote that Avis was worth “her weight in fresh truffles.”

Like many historians blessed with a surfeit of primary sources, Schweber occasionally overstuffs his biography. When the DeVoto family retraces the journey of Lewis and Clark, we learn that they ate potato pancakes, stayed in an art moderne hotel and visited a historic steamboat stop.

Bernard is reporting on a McCarran landgrab as they travel, yet his revelatory research sometimes vanishes beneath a blizzard of road trip play-by-play.

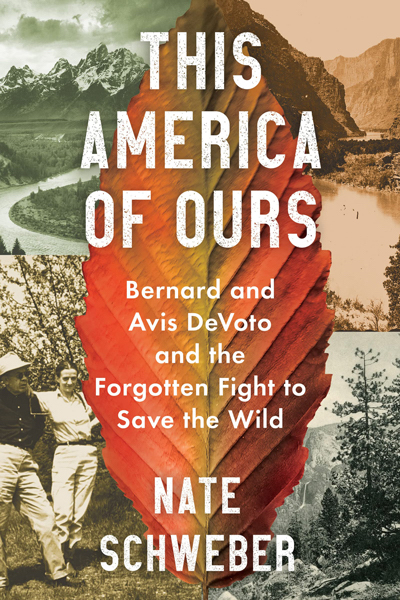

Bernard DeVoto. Photo: Wikipedia

This America works best when it situates the DeVotos in their broader context. Bernard and Avis spent much of their lives crusading against the proposed Echo Park Dam, an ill-conceived water-storage project that would have submerged Dinosaur National Monument and eroded protections for public lands. Although DeVoto didn’t live to see it, the anti-dam campaign he galvanized ultimately helped inspire the 1964 Wilderness Act. “Every national park with a canyon not stapled by a dam, a forest not pocked with clearcuts or mines, and grizzly bears or buffalo or peregrine falcons not replaced with cows and oil pumpjacks and powerlines,” Schweber writes, “remembers the DeVotos’ 1950s fight against the Echo Park Dam.”

If the couple’s legacy endures, so, too, do the forces they fought. In 2017, their younger son, Mark, sent a copy of “The West Against Itself,” one of his father’s most incisive essays, to Ryan Zinke, Donald Trump’s Interior secretary, whose gutting of Bears Ears National Monument would have delighted McCarran. There’s no indication that Zinke ever read it, but if he had, even he might have stopped short at these lines: “It is the forever recurrent lust to liquidate the West that is so large a part of Western history. … The future of the West hinges on whether it can defend itself against itself.”

This post was originally published at High Country News and appears here with permission. Top photo: Matthew Dillon/CC via Flickr

Discussion about this post