You are what you eat, the old saying goes, and that holds true for many animals that regularly ingest poison. For certain species that feed on toxic fare like plants and insects, not only do the poisonous meals do these creatures no harm, but the consumers actually co-opt the toxins. They become poisonous themselves for protection from parasites or predators.

Noah Whiteman, a University of California, Berkeley, evolutionary biologist and author of Most Delicious Poison, says the adaptations enabling this are favored by natural selection. Genetic mutations that help a species resist toxins can become widespread over time, and others may arise that help animals actually store the poisons and take advantage of them for their own defense. We’ve spotlighted some of the most remarkable of those adaptable species below.

Monarchs munch milkweed

A monarch butterfly rests on milkweed. Creative Touch Imaging Ltd. / NurPhoto via Getty Images

Monarch butterflies are beautiful backyard favorites—but they’re also toxic. Monarchs lay their eggs on milkweed plants, where caterpillars devour leaves containing poisonous cardiac glycosides compounds. The monarchs store these toxins in their own bodies to deter predators—and the insects’ appealing black and orange color signals this toxicity.

The monarchs evolved to digest the toxic plant through just a few key genetic mutations—ones that scientists have recently uncovered. Unfortunately for the butterflies, some of their predators, including black-headed grosbeaks and eastern deer mice, have also evolved mutations enabling them to devour the insects and tolerate the toxins.

“It looks like in this situation there might be an evolutionary arms race up the food chain,” says Simon Cornelis “Niels” Groen, an evolutionary systems biologist at the University of California, Riverside. The monarch’s ancestors evolved the ability to withstand toxins in milkweed. Later, under pressure from predators and parasites, the butterflies evolved the capacity to accumulate those toxins for protection. “Several predator and parasite species then in turn evolved mechanisms that overcome the toxicity of the butterflies,” he says. Some poison-resistant birds, he points out, may now actually use the telltale black and orange warning coloration to find the monarchs and eat them.

Poison frogs eat toxic insects

A strawberry poison frog rests on a leaf. Philippe Clement / Arterra / Universal Images Group via Getty Images/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c6/6c/c66cce9f-4605-415a-b7ea-09cd81ae3cfb/gettyimages-1371845688_web.jpg)

Poison frogs are famed for their brilliant colors and for the warning those colors convey to predators: Eating me is a bad idea! Predators that try to consume the amphibians will find the toxic taste unpleasant or worse, and they will later remember the bright-hued frogs are potential meals to be avoided.

In the rainforests of Central and South America, the frogs devour a particular diet to build up their poisonous defense. They eat bugs, including ants, beetles, termites and others, that contain toxins. The poison accumulates in the frogs’ skin. The poison is 200 times more potent than morphine in some species, and it is stored in skin glands and secreted when the frog is threatened. Tasting these toxic frogs can cause predators to become sick or even die.

In captivity, when these frogs are served a different diet including non-toxic zoo fare like crickets and fruit flies, they become less toxic, or not poisonous at all. Researchers at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute have experimented with poison-supplemented diets to make captive frogs toxic to predators, as they are in nature, so they can better survive reintroduction to the wild.

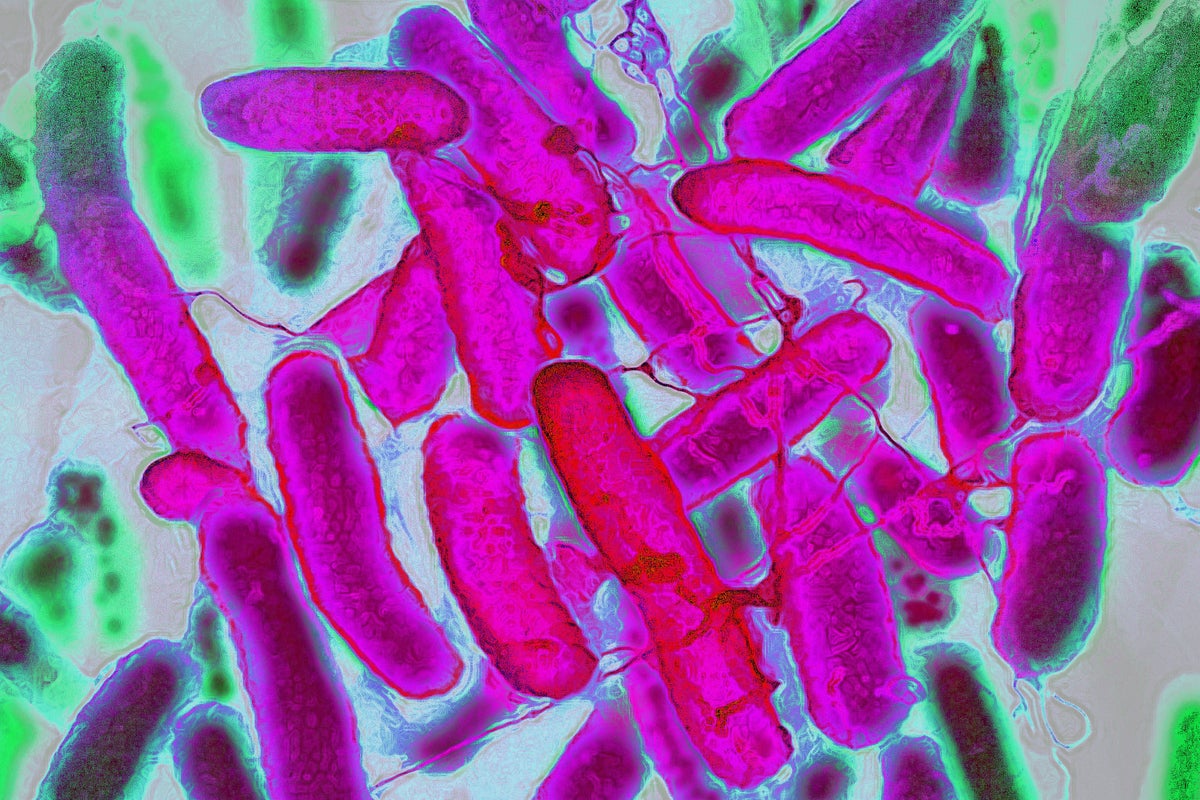

Pufferfish consume poisonous bacteria

A pufferfish swims over the seafloor. Ozge Elif Kizil / Anadolu Agency via Getty Images/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/91/88/91884224-5ebd-4593-838f-463a03a342ca/gettyimages-1183691473_web.jpg)

Pufferfish are famous as a Japanese delicacy known as fugu. If the fare is improperly prepared, it can quickly prove fatal to human diners, who may die within a few hours of ingesting the meal.

Pufferfish poison is known as tetrodotoxin, or TTX. It attacks nerve cells to cause paralysis, and sometimes death, by suffocation or heart failure. This potent toxin isn’t produced by the pufferfish but by bacteria living in the fish’s gut. The fish likely get the poison-producing microbes from a diet of algae and invertebrates. The fish have evolved a genetic mutation that safeguards their own nerve cells from TTX’s impacts. Meanwhile, the neurotoxin accumulates in the fish’s skin, and in organs like the liver, where it can paralyze or kill predators, including humans.

But this type of defense might not be the only reason the fish host poison-producing microbes. Some studies suggest that TTX may also serve as a stress reliever, which lowers levels of hormones like cortisol, making the fish less aggressive and promoting growth.

Birds may get toxic feathers from eating beetles

A regent whistler perches on a branch. David Tipling Photo Library / Alamy Stock Photo/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/9c/bc/9cbcbcb6-0ebf-4674-a0a0-897a0547f471/c8xepm_web.jpg)

Songbirds in the pristine rainforests of New Guinea, including the regent whistler and rufous-naped bellbird, have potent neurotoxins in their feathers like those found among poison dart frogs. Contact with the toxin batrachotoxin (BTX), 250 times more toxic than strychnine, can lead to muscle cramps, convulsions and even death by cardiac arrest in larger amounts. But the low dose in bird feathers causes tingling hands and watering eyes among humans, rather than lethal reactions.

This type of toxicity is rare, though not unknown, among the world’s birds. Kasun Harshana Bodawatta, who studies molecular ecology and evolution at the University of Copenhagen, was part of the team that discovered these toxic birds. Bodawatta says the source of the feathers’ toxins isn’t yet clear, but it may be a family of poisonous . “Given that not all individuals of toxic bird species carry BTX, we believe that the toxin enters bird’s body with diet,” he explains.

Bodawatta says the birds may benefit from BTX because it may reduce parasite pressures from ticks and lice, or deter mosquitoes and midges. And even though the birds don’t have it at lethal levels, the toxin still puts off one apex predator. “One thing we found out while doing our field work was that New Guinean people do not like eating these bird species,” he says. “They think they have a little “spicy” taste.”

Sea slugs nosh on stinging cells

A nudibranch crawls over the ocean floor. Andre Seale / VW PICS/Universal Images Group via Getty Images/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/10/8f/108f8fd5-8d3b-4b96-8506-407e5ccc4a7e/gettyimages-1288684641_web.jpg)

Nudibranchs are a family of photogenic sea slugs known for appearing in a diverse psychedelic array of colors and shapes. Many of these quirky-looking animals have an equally unusual diet—sea anemones. Those colorful invertebrates cling to rocks or coral and resemble underwater flowers. But they ambush passing fare, from plankton to fish, with their tentacles armed with nematocysts.

Nematocysts are stinging cells, like a tiny, toxic barbed spear, that are triggered when a predator brushes or touches the anemone. But nudibranchs are adapted to withstand this type of attack. Their mouths and throats boast a tough coating that allows them to swallow the tentacles, barbs and all, with no ill effects. Then they turn this weaponry to their own advantage.

Rather than digesting nematocysts, nudibranchs absorb the toxin-filled stinging cells to become part of their defensive array. The cells are transported through the body to the sea slug’s appendages, where they are stored in sacs until they are fired off as a defense if the slug is under attack.

Rattlebox moths down a toxic plant

A rattlebox moth at rest Laura Gaudette – https://www.inaturalist.org/photos/70374412 via CC By-SA 4.0/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8a/f5/8af5344c-2f81-442b-acd0-20795390e560/utetheisa_ornatrix_70374412_web.jpg)

As larvae, male rattlebox moths devour the toxic leaves of the rattlebox plant, acquiring chemicals that remain with them as adults and make them distasteful to spiders. But females don’t feed on the plant. Instead, they derive its protection in a very unexpected way. Each male’s sperm is laden with the plant’s toxic chemicals, called pyrrolizidine alkaloids, which after mating spread throughout the female’s body to protect both her, and her eggs, from predators. Females retain this protection for life—though that’s only about 30 days for an adult.

Spiders find the toxin-protected moths extremely distasteful—so much so that they turn them loose from their webs. Those without the protective poisons, such as females that have not mated, are readily eaten by the same spiders.

This poisonous sperm package is so valuable that females actually size up suitable mates based on cues about it. Females can sense a chemical derivative of the toxins, released into the air by courting males, which advertises how much of the protective poison the suitors have. The more poisonous the aura a given male exudes, the more suitable he seems.

Top Image Caption: Creative Touch Imaging Ltd. / NurPhoto via Getty Images; Philippe Clement / Arterra / Universal Images Group via Getty Images; David Tipling Photo Library / Alamy Stock Photo; Andre Seale / VW PICS/Universal Images Group via Getty Images; Laura Gaudette – https://www.inaturalist.org/photos/70374412 via CC By-SA 4.0

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/43/dc/43dc0f07-5eed-4577-9c92-63190e3c621a/toxicanimals-2024-v2.jpg)

Discussion about this post