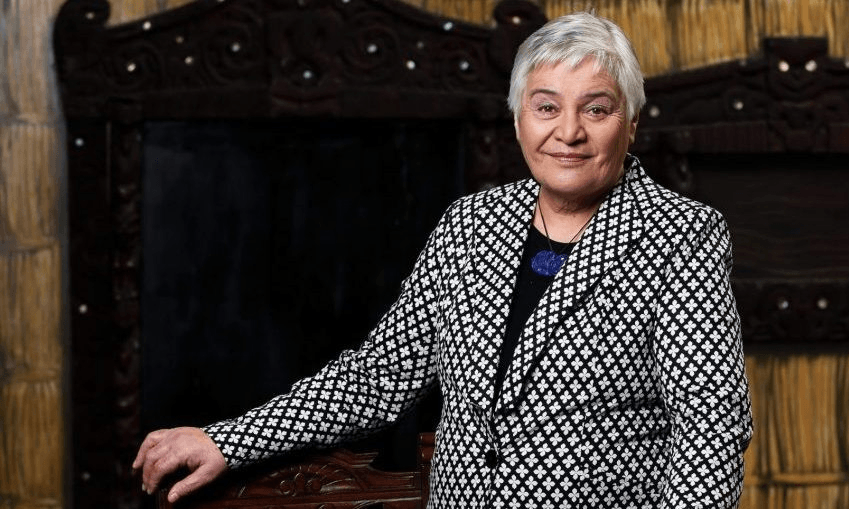

The co-founder of Te Pāti Māori and architect of Whānau Ora will be remembered as a skilled political tactician who dedicated her life to the wellbeing of Māori, writes Miriama Aoake.

Part of the hesitation of entering politics for any sane person is surely compromise. Compromise is essential in the Beehive, but the degree of severity and consequence varies. Does this compromise align with personal ethics, promises made to constituents, does it tow the party line? How does one perform, sell or leverage said compromise as a necessity, and will voters agree? Dame Tariana Turia (Whanganui, Ngā Wairiki Ngāti Apa, Taranaki, Ngāti Tūwharetoa) will be remembered as someone understood the art of compromise. An architect of Whānau Ora, Smokefree Aotearoa and Te Pāti Māori, Turia’s legacy is one that belies a waning art in politics: knowing when to compromise, and how to make it count.

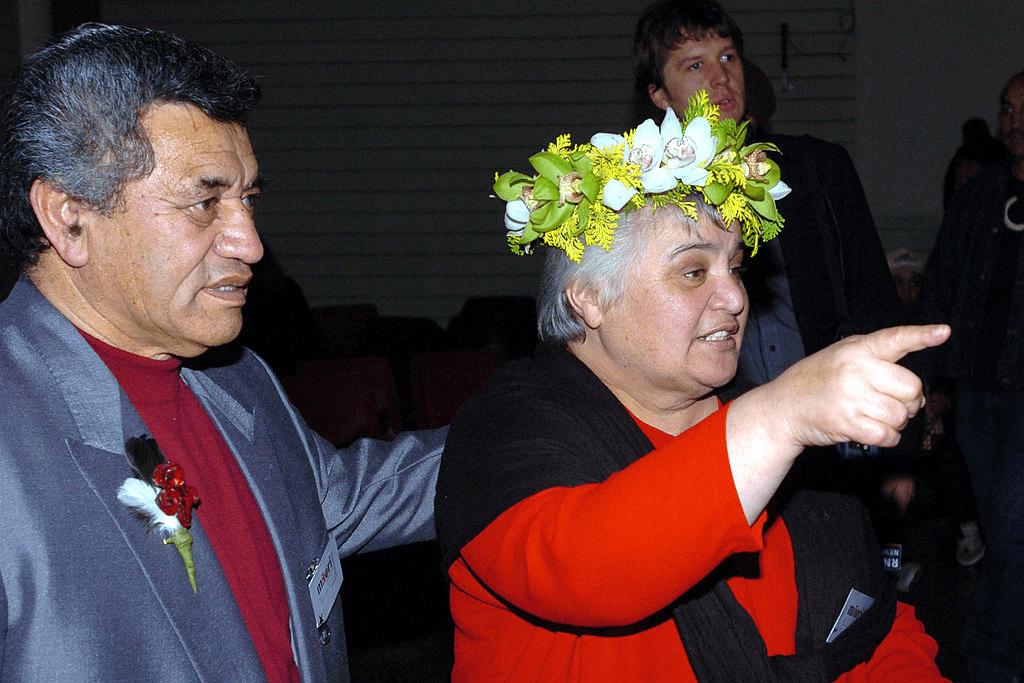

Tariana Turia’s life was service to the people. Prior to entering politics, Turia was a leader in the reclamation of Pākaitore (Moutoa Garden) in 1995, formerly a memorial to the suppression of mana whenua, in an occupation that endured for 79 days. This, she described, was a formidable time in her life, a time and space in which pakeke, kaumātua and rangatahi of Whānganui stood together in all that it means to be Māori. She had worked in Te Puni Kōkiri and established Te Oranganui Iwi Health Authority; she ran decolonisation workshops with whānau, for whānau.

She had the mandate of her people, through Pākaitore, to stand for election in 1996 as a list MP. In 2002, she would relinquish her position as a list MP, in order to contest (and win) the Te Tai Hauāuru seat. The following year would prove a catalyst for momentous change, both in the trajectory of Turia’s career and Crown-Māori relations.

To refresh, the Court of Appeal overturned a decision from the High Court that ruled the foreshore and seabed did not fall under the definition of customary land, and that Ngāti Apa could pursue a determination through the Māori Land Court. The government intervened before this pursuit could come to a fruition, and ruled that the foreshore and seabed belonged to the Crown. Turia recalled receiving only one email that asked her to vote with the Labour Party, and only because the alternative – being booted from parliament – was worse.

For Turia, there was no alternative. Despite the suffocating pressure bearing down from the Labour Party – the Crown – Turia voted against the bill and resigned. Helen Clark, then-prime minister, sacked her from her ministerial role. Her resignation triggered a by-election for the Te Tai Hauāuru seat and, having formed Te Pāti Māori alongside Tā Pita Sharples, spearheaded a new chapter for Māori politics. In the 2005 general election, the Māori Party contested in all seven Māori electorates, and won four of seven seats. Under incredible strain and pressure, Turia refused to compromise, to sell her people down the river.

Under the Labour government, Turia laid tracks through which her greatest contribution – Whānau Ora – would later be established. In 2002, Turia developed He Korowai Oranga, a distinct Māori health strategy that drew on previous policy attempts to deliver better health outcomes for Māori, by Māori. The primary objective, she stated, was to empower families to realise their health and wellbeing potential, by shifting the focus of delivery from the individual to the collective, the whānau.

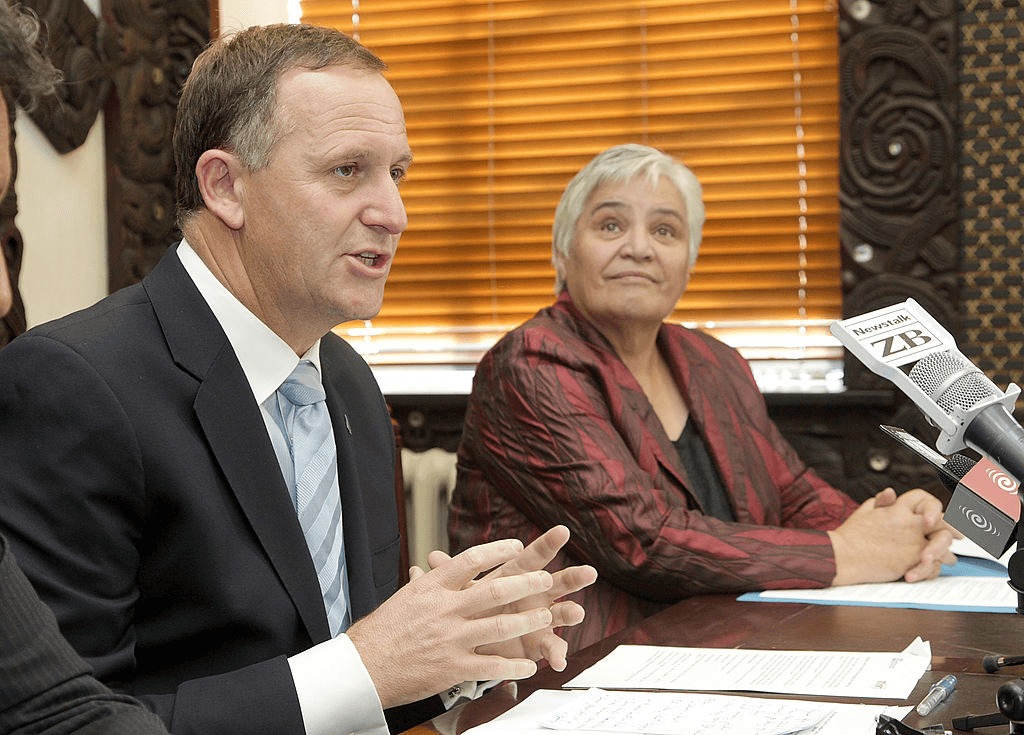

In tandem with the New Zealand Public Health and Disability Act 2001, which sought to explicitly integrate Te Tiriti o Waitangi into health policy and increase Māori participation in decision-making and service delivery, He Korowai Oranga stressed the need for self-determination. In 2008, the coalition agreement between Te Pāti Māori and the National Party helped to translate a campaign initiative – Whānau First – into a policy reality, Whānau Ora.

The Confidence and Supply Agreement reached in 2008 forced difficult conversations within the Māori Party. When National announced a hike in GST of 2.5% in 2010, Turia’s hand was forced. Hone Harawira refused to vote for the rise, and though Turia respected Harawira’s dissent, to the public, Te Pāti Māori looked divided. For her part, Turia was devastated.

In the same year however, Turia delivered on Whānau Ora. To the broader policy environment, this was a policy operationally difficult to define. At once, Whānau Ora encapsulates the desired outcome, the kaupapa and the mode of engagement. Put simply, it means family wellbeing. It is a strengths-based approach, aiming to foster collaborative relationships across state agencies to meet with, and deliver on, a whānau-actioned plan for better health outcomes.

Through Whānau Ora, Turia spearheaded a cross-sector shift from treating the individual to the collective, and empowering whānau to “become the authors of own our destiny”, as she Turia put it. It’s a contribution that may take generations to appropriately measure. While Turia was forced to compromise on GST, she made sure to deliver on Whānau Ora.

This year, we were meant to be smokefree. Tariana Turia adopted the plan through the Māori Affairs Select Committee in 2010. The plan prevented retail displays of tobacco products, reduced duty-free allowances, increased the excise tax and initiated plain packaging. Adult smoking rates dropped from 21% in 2006 to 15% in 2013. The Smokefree 2025 campaign was a path from which Turia would never stray, and her legacy on these issues is one that now passes to us all. It is a legacy that, at its core, is concerned with the wellbeing of the collective: a principle Dame Tariana Turia committed her life to. Her impact, her contributions and service to us all, is one we cannot afford to compromise.

Discussion about this post