By: John Elliott

Rahul Gandhi has stepped up his Congress Party’s claim to lead Opposition parties in next year’s general election by saying that the campaign “has to be structured around the Congress” which has “the ideological spine” and “foundational ideology” needed to defeat Narendra Modi’s ruling Bharatiya Janata government.

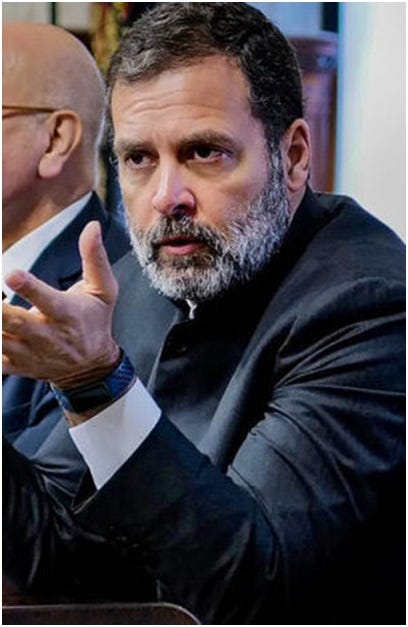

Regional parties such as north India’s BSP and RJD don’t have “the necessary ideology” to tackle the BJP and its hardline mother organization, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), Gandhi told me in London on March 6 at the end of a week-long speaking tour.

This is controversial because, while Opposition unity is essential to challenge the BJP, regional parties in states like Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, West Bengal, and Tamil Nadu are not prepared, so far at least, to allow what they regard as the elitist Congress to be in the lead. Some of the parties’ leaders have their own political ambitions to become prime minister, and they do not see either Congress as a party, or the Gandhi dynasty, as vote-winners.

The regional parties would also argue, to varying degrees, that they do share the Congress’s ideology of non-violence, democracy, free speech, and openness. Gandhi’s point is that Congress would pull this together nationally.

It is not yet clear whether Gandhi himself wants to lead the campaign and be prime minister, or whether he would nominate someone else, as his mother Sonia Gandhi did in 2004 when she passed the PM’s post to Manmohan Singh.

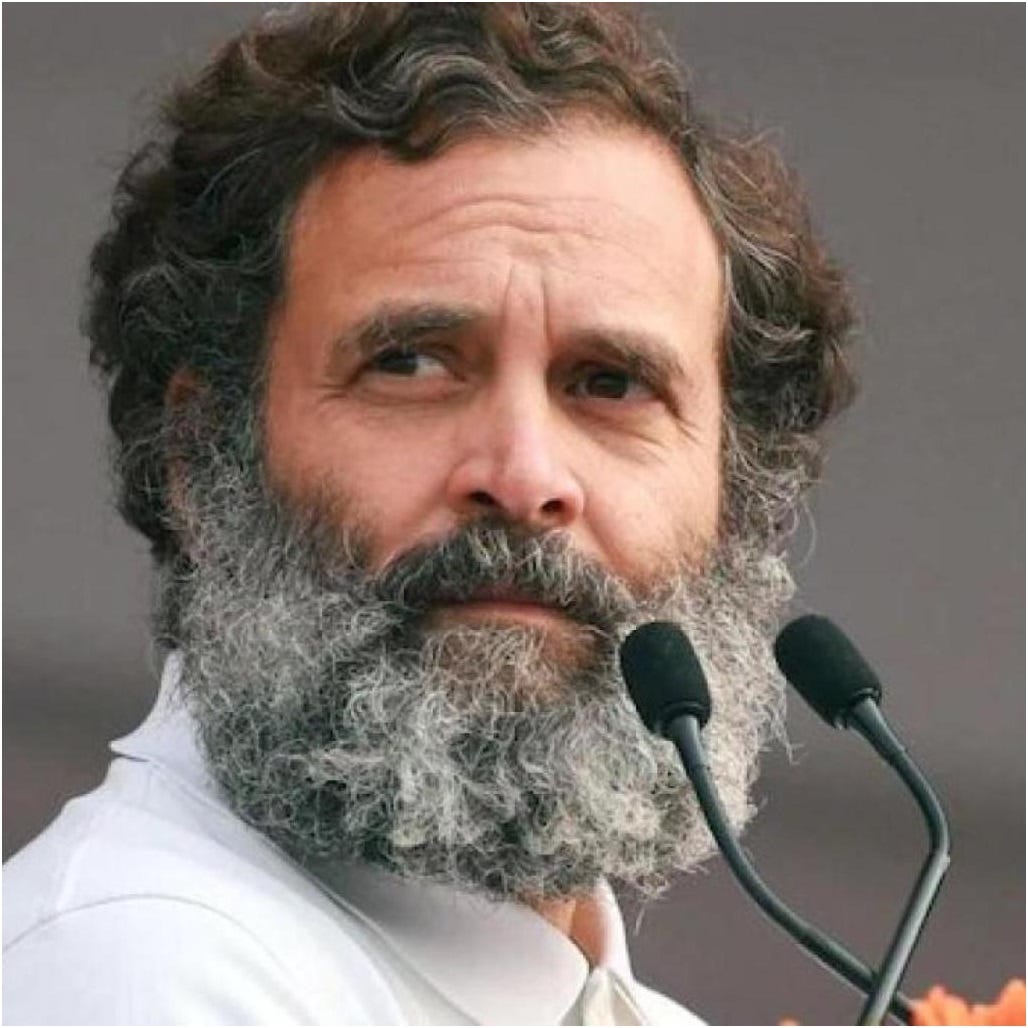

Gandhi didn’t answer when I asked him about his ambitions. But he is showing all the signs of building up his personal image, even though he resigned as Congress president in 2019 after the party suffered a series of election failures under his leadership.

Starting last September, he led a mammoth 4,000-km 146-day “yatra” (journey) from Tamil Nadu in the south of India to Kashmir in the north. When it began, Congress was preparing for a non-Gandhi president to succeed his mother and, in December, a veteran politician, Mallikarjun Kharge, was elected.

At age 80, Kharge has been active in politics for 50 years but is no challenge to the Gandhi dynasty. That leaves Gandhi, age 52, free to step in at some stage if he reverses what he has said for the past four years about the dynasty not holding the top post.

The yatra looked odd when it began, almost like the last gasp of an unwilling and unsuccessful politician trying to regain some public credibility. Over the weeks, however, that changed as politicians from Congress and other parties, along with social activists, local leaders, and others, joined the crowds of thousands who followed Gandhi day by day. They included two notable economists – Raghuram Rajan, former governor of the Reserve Bank of India, and Jean Dreze, a leading social scientist, both critics of the Modi government who were publicly showing their support for Congress.

The yatra has been the peg for most of the speeches that began in Gandhi’s old university city of Cambridge last week and continued in London where he has addressed the Indian diaspora, Indian journalists, parliamentarians (in a House of Commons committee room), and Chatham House policy institute.

Gandhi said the main purpose of the 4,000km journey was to listen to people because their views were not being heard in Delhi. In his speeches in the UK, he turned that into an attack on the Modi government, saying the yatra was necessary because “the structures of our democracy are under brutal attack – media, institutional frameworks, judiciary, Parliament.” It was not possible to air views and have debates – something he could do in London and Cambridge.

When I asked Gandhi what he has learned most from his march, he said that “above everything else,” it was the failure of the country’s “economic model” to manage prices and produce jobs. “People pay for their children’s education, and nothing comes of it because of a lack of jobs – it’s a waste of money,” he said, airing a widespread problem.

That and other attacks led to furious responses from the Modi government that blamed Gandhi for breaking diplomatic convention by defaming India while abroad. Gandhi replied that Modi had done the same by claiming in speeches abroad that nothing had been achieved in India’s development when the Congress was in power for decades.

But while his attacks on the government were clear, Gandhi has not successfully mapped out how a new government would solve the economic problems that dominated the yatra. In several speeches, he put forward a complicated idea that democratic economies such as the US and India had lost their production and manufacturing prowess to non-democratic “coercive” China, so a new model was required.

“We need new thinking about how you produce in a democratic environment compared to a coercive environment,” he told students in Cambridge and academics in London.

“We need small and medium industries and reimagined production, manufacturing in a modern way, in a decentralized and technological way,” he said without spelling out what he was envisaging for a country that has never been regarded as having a manufacturing economy.

Leaders of states, hearing these remarks, will surely conclude that they will do better selling their own regional economic successes in the general election rather than relying on a Congress lead and model.

In 2018 when Gandhi made his first major UK visit as Congress president, he talked about the need to build an election platform based on opposition to five developments that had emerged under the Modi government. They were growing country-wide violence, attacks on basic freedoms, a lack of concern for minorities and the weak, the imposition of “a very rigid, hate-filled angry ideology”, and attempts to “capture and destroy” institutions.

Following his yatra, he is now also majoring in people’s economic problems, which are always uppermost in voters’ minds at elections, along with the need for Congress to have a leading role.

He has referred to the Congress role a couple of times in the past, but not so specifically as he did to me after he left his final London speaking engagement and talked about the campaign being “structured” around the Congress’s “ideological spine” and “foundational ideology.”

There appears however to be widespread acceptance of Modi’s Hindu nationalism and authoritarian government, with Muslims having to accept that India is primarily a Hindu country, which is the reverse of Congress ideology.

If that is correct, voters seem likely to go for the party or coalition that offers a positive view of the future with jobs and tolerable price rises. Presumably, Rajan and Dreze are working on that, and helping Gandhi develop his thoughts into sound economic policies to attach to Congress’s spine and ideology. That is what is needed if the party is to have any chance of gaining the leading Opposition role that Gandhi advocates.

John Elliott is Asia Sentinel’s South Asia correspondent. He blogs at Riding the Elephant.

Discussion about this post