| Dear Readers: As we look ahead to next week’s New Hampshire primary, we are pleased to feature a piece from our friend Dante Scala of the University of New Hampshire, who identifies the key places to watch in next week’s Republican contest. We also spoke with Dante about New Hampshire in the latest edition of our Politics is Everything podcast, which will be available wherever you get your podcasts.

— The Editors |

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— Polls suggest that, at the very least, New Hampshire should be more competitive than the blowout won by Donald Trump in Iowa. If New Hampshire is close, it wouldn’t be unusual in the Granite State’s first-in-the-nation GOP primary.

— While we typically look at counties to analyze trends, New Hampshire provides data at the city/town level, and there is a smattering of key places to watch.

— In order to win, Nikki Haley will have to greatly build on John Kasich’s 2016 showing in some key places.

A New Hampshire roadmap

The winnowing of the GOP presidential field both before (Chris Christie) and after (Vivek Ramaswamy) Donald Trump’s big victory in Iowa reduces the field of notable Republican presidential contenders to just three: Trump, along with Nikki Haley and Ron DeSantis. Unlike Iowa, New Hampshire may produce a close finish. This would not be unusual for the Granite State: 3 of the last 6 competitive presidential primaries have been decided by fewer than 10 percentage points (Bernie Sanders edged out Pete Buttigieg in the 2020 Democratic primary, while both Hillary Clinton and John McCain won close victories in 2008). In the event that exit poll analysts declare the Granite State “too close to call,” what information should the savvy election observer seek as returns come in?

Just 4 of New Hampshire’s 10 counties—Hillsborough and Rockingham, on the Massachusetts border; Merrimack, which contains the state capital of Concord; and Strafford, home of the University of New Hampshire—will likely comprise 75% of the primary electorate. But aggregate, county-level results won’t be available until the wee hours of the morning, if not the day or two afterward. For in-the-moment analysis, psephologists have to zoom in on New Hampshire’s cities and towns in order to piece together a picture of the final results. The following is a guide to which New England hamlets will offer the best clues to the ultimate outcome on Tuesday, Jan. 23.

One factor that distinguishes this contest from previous ones is the degree to which voters already have sorted themselves along ideological lines. In the latest New Hampshire survey from Suffolk University, Trump enjoys the support of two-thirds of conservatives while a majority of moderates back Haley. This divergence speaks to Trump’s dominance of the Republican Party: As political scientists Daniel Hopkins and Hans Noel have demonstrated, voters define a person’s degree of conservatism these days, at least in part, by how they view the former president.

All of this should make it somewhat easier to identify key municipalities in New Hampshire that will offer solid clues to the primary’s outcome, based on previous elections here. The 2016 Republican primary, which Trump won with 35% of the vote, is such a proxy for next week’s contest. Although Trump’s range of outcomes across counties was modest (from a low of 29% in Grafton to a high of 39% in Rockingham), there were a handful of municipalities where he performed especially well or poorly (at least 5 percentage points better or worse than his statewide vote percentage). As a proxy for the strength of moderates in a municipality, I use the performance of 2016 second-place finisher John Kasich. The former Ohio governor, who preached the virtues of bipartisanship during his campaign, won 16% of the vote statewide, but almost doubled that support among moderates, according to exit polls.

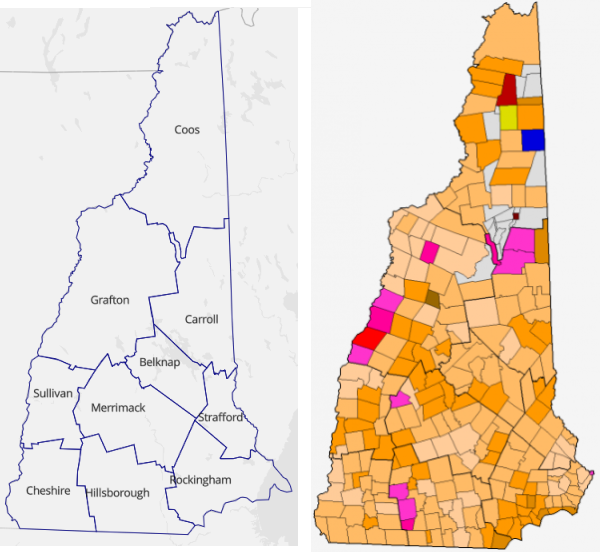

With these two proxies in mind, let’s take a tour of the Granite State. Readers can use Map 1 as something of a guide: The left map shows the counties in the state, and the right map shows the 2016 results by city/town. Trump carried all 10 counties, but Kasich did win a smattering of places across the state at the city/town level. We’ll call out important towns and cities on the map in the text, when possible to do so.

Map 1: NH counties plus 2016 GOP primary results by town

Notes: On the city/town map on the right, 2016 Donald Trump wins are in shades of orange/brown and John Kasich wins are in shades of pink/red, with darker shades representing higher vote shares. Blue represents a tie (Trump got a single vote and Jeb Bush got a single vote in sparsely-populated Cambridge Township) and Ted Cruz (yellow) won a single, tiny township, Millsfield. Light grey means no votes were cast.

Source: Dave’s Redistricting App for county map, Dave Leip’s Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections for 2016 presidential primary map

Hillsborough County

Hillsborough, which contains the state’s two largest cities, Manchester and Nashua, represented nearly 30% of the primary vote in 2016. Both Trump and Kasich performed about as well in Hillsborough as they did statewide. But both also had particular pockets of strength. The eventual winner performed especially well in towns along the Massachusetts border, such as Pelham (52%), Hudson (43%) and New Ipswich (40%), some of which are in darker shades of Trump orange/brown along the southern border on the map; and rural towns in the county’s northwest corner, including Windsor (45%), Hillsborough (43%), and Deering (42%). Kasich, in contrast, was especially popular in towns west of Manchester along Route 101, which runs across the state’s southern tier. Expect Haley to do especially well in “Kasich towns” such as Sharon (32%, double his statewide percentage), Peterborough (23%), and Hancock (22%)—those three, running from south to north in the order listed above, are the three Kasich-shaded towns in the southern part of Map 1.

The town of Bedford could prove pivotal to the primary’s outcome. For one, its residents cast some 7,000 votes in 2016, the third-most in the county, behind only Manchester and Nashua. Just as importantly, Bedford is full of well-off, well-educated residents who were repelled by the Trump presidency. In 2016, Trump performed 7 points worse here than statewide. And in the 2020 general election, Joe Biden carried the town, historically one of the most Republican in the state. If Haley is to have a chance to pull off an upset, she has to win Bedford and upscale towns like it decisively. If Trump carries it, take it as a sign that a significant number of college-educated Republicans have joined his working-class base.

Rockingham County

Rockingham County, which sits in the southeastern corner of the state along the Massachusetts border, will almost match adjoining Hillsborough in turnout. In the 2016 primary, one out of four voters came from Rockingham. Eight years ago, Trump performed best here, carrying 39% of the vote. More than half of the voters in Seabrook, a working-class town that juts out toward the Atlantic Ocean, cast ballots for him, his second-best performance in the state. Trump’s greatest strength, however, was closer to Interstate 93 in the western half of the county, which contains both large, well-developed areas as well as smaller exurbs. In town after town there, Trump carried 40% or more of Republican voters. If Trump’s current poll numbers hold on primary day, expect him to win a majority in places such as Danville, Plaistow, Salem, Sandown, Raymond, Atkinson, Derry, Fremont, and Windham (note the darker Trump shades in the state’s southeastern corner). Conversely, if there is a Haley upset in the wind, expect her to hold her own here and keep Trump’s margins of victory narrow.

Republican Gov. Chris Sununu, Haley’s chief ally, lives on the other side of the county in Newfields, not far from the Seacoast. (Former state House Speaker Doug Scamman, another Haley endorser, owns a farm in nearby Stratham.) The eastern half of Rockingham, known for its old wealth and moderate Republican politics, contained some of Kasich’s best areas in 2016, such as Stratham, Greenland, the city of Portsmouth, Rye, Exeter, and New Castle (the little speck of Kasich pink along the eastern border in that part of the state). Haley should be able to establish a beachhead in Rockingham—but that will not be enough if Trump has a strong night on the western side of the county.

Strafford and Merrimack counties

North of Rockingham is Strafford County, home of the state’s University of New Hampshire. One of 12 Republican primary voters came from this county in 2016. Towns in the orbit of the state university—Durham, Lee, Madbury, and the city of Dover—which lean strongly Democratic in general elections, will be test cases for whether Democratic-leaning independents have elected to crash the GOP primary and cast votes for Haley (or in their minds, against Trump). Trump should be on firmer ground further north in the county, in small towns such as Farmington and Milton. Rochester and Somersworth, two small working-class cities, will be bellwethers to watch.

A similar dynamic between center and periphery should play out to the west of Strafford in neighboring Merrimack County, which contained 12% of Republican primary voters in 2016. Eight years ago, Kasich performed especially well in the state capital of Concord and towns in its environs, such as Bow and Hopkinton. Further away from the capital, Trump did especially well in small towns such as Allenstown and Northfield, as well as the city of Franklin. (Bear in mind, cities in New Hampshire are sometimes small entities; just 1,500 voters cast Republican ballots in Franklin in 2016.)

Northern and western New Hampshire

The remainder of the Republican primary vote—about 25%—is scattered across 6 other counties to the north and west. They are largely rural, but they are also a reminder that not all rural is equally friendly toward Trump. On the Vermont border in the Connecticut River Valley, Trump posted a strong performance (37%) in Sullivan County, in such areas as Newport and the city of Claremont. But north and south along the valley, Trump’s performance declined in counties containing institutions of higher learning. This trend was especially pronounced in Grafton County, home of Dartmouth College and Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center. Kasich’s best countywide performance was in Grafton (21%), especially so in the college town of Hanover and its environs (Lyme, Orford, and the city of Lebanon). These are the four Kasich-won municipalities along the state’s western border with Vermont, running Orford, Lyme, Hanover, and Lebanon from north to south.

Conclusion

A couple of weeks ago, Haley made what some saw as a gaffe when she suggested that New Hampshire would “correct” whatever Iowa did. As impolitic as that may have been, there is some truth to it. The last three non-incumbent Republican nominees—John McCain in 2008, Mitt Romney in 2012, and Donald Trump himself in 2016—all failed to win Iowa but then captured New Hampshire on the way to the nomination. This does also sometimes work the other way, though: The two non-incumbent winners before them, Bob Dole in 1996 and George W. Bush in 2000, won Iowa before stubbing their toes in New Hampshire. Clearly, winning both early-state contests is not a requirement to be the GOP nominee.

Eight years ago, New Hampshire persuaded me that Trump’s support was solid when I saw how well he performed across divisions of class and socioeconomic status in the Granite State. Next week’s primary results, coupled with those of the Iowa caucus, will tell us a lot about how seriously to take Haley’s challenge to the former president. For Kasich in 2016, New Hampshire turned out to be a cul-de-sac. His message of bipartisanship found a niche here among moderates and liberals in places like Hanover and Durham, but failed to resonate among mainstream conservatives, in New Hampshire and elsewhere. Ominously, Haley’s best performance in Iowa was in Johnson County, home of the University of Iowa. Next Tuesday may tell us whether she is a Dartmouth College professor’s ideal of a good Republican, or if she has laid the groundwork of a broader base of support in her party.

| Dante J. Scala, a professor of political science at the University of New Hampshire, has been watching presidential primaries since 2000. He has written two books on New Hampshire and the presidential nomination process: Stormy Weather (2003), and with Henry Olsen, The Four Faces of the Republican Party (2015). |

Discussion about this post