The extreme rainfall that hit Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iran in April and May this year was made twice as likely by El Niño, a new rapid attribution study shows.

The World Weather Attribution service finds that spring rainfall over the region has become 25% heavier over the past 40 years.

As climate models were unable to reproduce this trend, the authors were unable to assess the impact of rising global temperatures on the event. However, a study author tells Carbon Brief that she “would be extremely surprised if climate change is not at least part of this trend”.

In contrast, the authors were able to identify the influence of the strong El Niño event that has been underway in the Pacific Ocean since the autumn of 2023.

They find that such heavy rainfall would be expected once every 20 years in the absence of El Niño, but this frequency rises to once every 10 years when an event occurs.

Flash flooding

In the spring of 2024, a series of unseasonably early spring storms swept across large parts of central Asia, causing severe flooding which destroyed homes and crops, and killed thousands of people.

In Pakistan, the first spell of intense rainfall began on 12 April. The resulting flooding damaged more than 450 schools and 5,000 houses, and killed more than 100 people. Subsequent periods of heavy rainfall across the country caused further damage to buildings and crops, destroying huge fields of wheat that were ready for harvest.

The flooding “has resulted in significant economic losses for local farmers and communities, compounding the losses from the rain-related incidents”, the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs warned.

Afghanistan also suffered a series of deadly floods. After a dry winter, which made the soil less able to absorb rainfall, the country was hit by waves of intense rainfall throughout much of April and May,

About 70 people were killed in April after flash floods destroyed about 2,000 homes, three mosques and four schools. On 10 May, another period of intense rainfall hit the country – especially in the north-east, resulting in hundreds of fatalities and many more missing people. Around 9,100 livestock and 20,800 acres of agricultural land were destroyed.

Five days later, the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies warned that 25 out of 34 provinces in Afghanistan had been affected by flooding, adding that “thousands of displaced people have no homes to return to after their houses were swept away”. The organisation also warned:

“This latest disaster is happening within the context of what is already one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises, where communities are already barely able to cope.”

Meanwhile, the Guardian reported that “in a country with a health system already on its knees, some health facilities were rendered non-operational last week by the flooding”.

Similarly, intense rainfall and flooding killed multiple people in Iran. The

Iran International Newsroom blamed “government mismanagement and flawed urban planning” for “exacerbating” the intense rainfall.

The study authors decided to focus on April-May rainfall in a region centred on Afghanistan, bounded by Iran on the west and Pakistan on the east.

The map below shows the difference in April-May total rainfall between 2024 and the 1991-2020 average, where blue indicates that 2024 saw heavier than average rainfall, and red indicates lighter than average rainfall. The region analysed in this study – covering parts of Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iran – is outlined in red.

The region’s main winter rainfall season runs from November to early April, meaning that this year’s intense rainfall was unusually early, the study says.

Attribution

The spring flooding over Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iran was “incredibly deadly”, according to the. To determine how likely this period of intense rainfall was, the authors analysed a timeseries of observed rainfall data to put the event into its historical context.

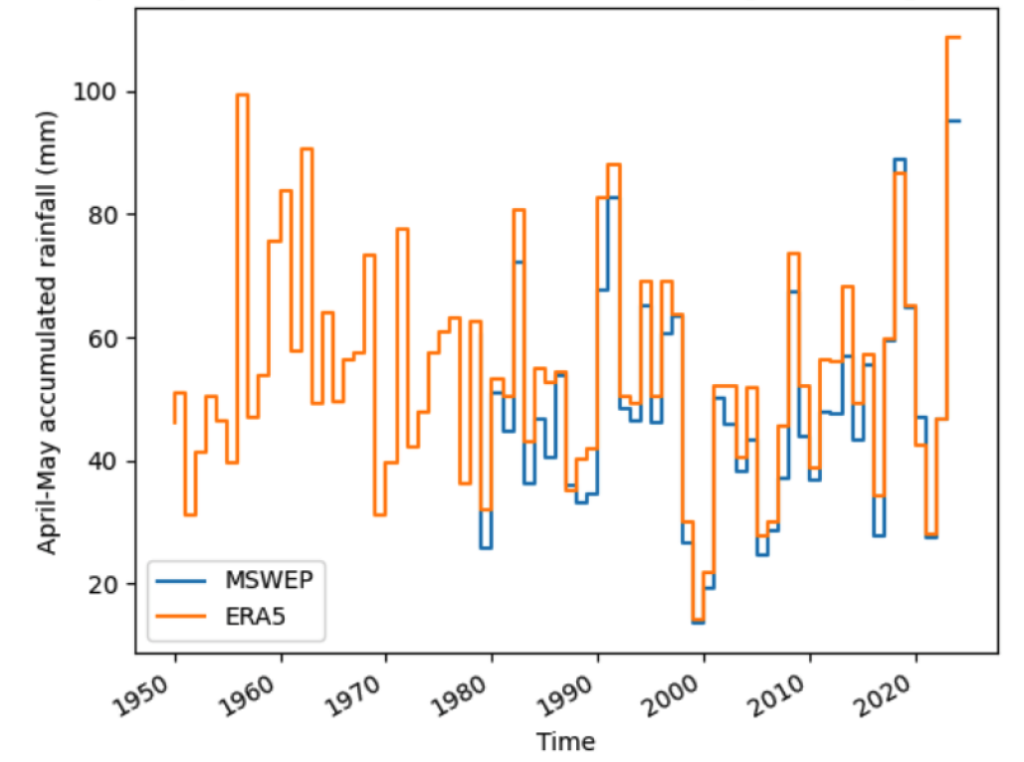

The graph below shows April-May rainfall from 1950 to the present day over the study region. The blue and orange lines indicate different datasets.

The observational data shows that April-May rainfall in the region has become, on average, 25% heavier over the past 40 years.

The authors conducted an attribution study to identify the “fingerprint” of climate change on the extreme rainfall trend. They used models to compare the world as it is today – which has already warmed by around 1.2C because of human activity – to a “counterfactual” world without climate change.

However, the climate models used in this analysis did not consistently reproduce the trends shown by observed data.

“We can’t formally attribute it because the models don’t reproduce these trends,” Dr Friederike Otto – senior lecturer in climate science at the Grantham Institute for Climate Change and the Environment at Imperial College London and co-author of the study – told Carbon Brief at a press briefing.

However, Otto – who is also a Carbon Brief contributing editor – explained that climate change is known to make individual storms more intense. “So I would be extremely surprised if climate change is not at least part of this trend,” she added.

The authors also investigate the impact of El Niño – a global weather phenomenon that originates in the Pacific Ocean – on rainfall in the region. The world has been experiencing El Niño conditions since around October 2023 and is now showing signs of ending.

Dr Mariam Zachariah, who is also study author from the Grantham Institute, told Carbon Brief that El Niño leads to warmer sea surface temperatures over the western Indian ocean, which are a “known driver” of extreme rainfall over the study region.

Using a series of statistical models, the authors determined that an El Niño during the winter (December-February) often leads to an increase in rainfall over the study period during April and May.

The 2024 spring rainfall over Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iran was not “particularly rare” in today’s climate, and could be expected to occur roughly once every 10 years if only El Niño years are considered, the authors find.

Under “neutral” conditions in the Pacific Ocean, similar periods of heavy rainfall are expected roughly once every 20 years, they add.

They conclude that El Niño doubled the likelihood of the extreme rainfall that hit Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iran in spring 2024.

(These findings are yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal. However, the methods used in the analysis have been published in previous attribution studies.)

Vulnerability

Afghanistan ranks fourth on the list of countries most at risk of a crisis, and eighth on the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative index of countries most vulnerable and least prepared to adapt to climate change.

However, the country has been absent from COP climate summits since the Taliban took over in 2021. No foreign government has formally recognised Taliban leadership and it does not have a seat at the UN General Assembly.

The Taliban’s takeover has impacted Afghanistan’s access to climate finance. The country’s climate plan estimates it needs $20.6bn over 2021-30. But around 32 large environmental programmes worth more than $800m were suspended when the Taliban took over, including a major rural solar installation project backed by the Green Climate Fund.

Nevertheless, the country is still receiving some climate finance. A recent freedom-of-information request by Carbon Brief shows that the UK government has opted to meet their £11.6bn climate finance target by “redirecting” or “relabelling” existing funds as “climate finance”, while failing to commit new money in sufficient volumes.

This includes reclassifying nearly £500m of aid for war-torn and impoverished countries, including Afghanistan, as “climate finance”.

And, in late April this year, the Taliban initiated its first discussions with the UN, donors and non-governmental organisations about the implications of climate change in Afghanistan, as confirmed by organisers.

However, in the meantime, Afghanistan remains highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change.

The authors say that many residents of Afghanistan – as well as Pakistan and Iran – are “highly vulnerable” to flash flooding, as many of them live on river basins that are highly vulnerable to flash floods.

Maja Vahlberg – a climate risk consultant from the Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Centre and author on the study – told Carbon Brief that “marginalised communities” were among the most severely impacted by the flooding.

The study adds that “displaced populations were particularly impacted, especially as limited essential infrastructure was destroyed and already vulnerable populations were exposed to more waterborne diseases”.

Vahlberg told Carbon Brief that, across the region, there is “limited” data sharing and flood risk management, meaning that flood early warning systems are “significantly less efficient” than they could be.

The study concludes that there are “ample opportunities to improve climate adaptation and resilience”, including “increasing the coverage of early warning systems, and improving flood risk management policy and planning”.

Sharelines from this story

.png)

Discussion about this post