Wildebeest – large African antelopes with distinctively curved horns – are famous for their great migrations on the grasslands of eastern and southern Africa. One hundred and fifty years ago, they migrated in huge numbers across the continent, in search of grazing and water and to find suitable areas for calving.

Migration is crucial to sustain their large populations. But their routes are being interrupted by roads, oil and gas pipelines, railway lines, fences, cities, livestock and farmland.

Today, the only remaining large migration is east Africa’s famous Serengeti-Mara migration. About 1.4 million wildebeest – accompanied by about 200,000 zebras, 400,000 gazelles and 12,000 eland – cover up to 3,000km every year in a cycle that follows seasonal rainfall patterns.

Even this migration is now threatened by plans for new roads and railways, uncontrolled and unplanned developments and exponential human population growth around the edges of the Serengeti-Mara ecosystem.

We’ve now found, in new research, that the disruption to the migratory route has genetic implications for the animals’ longer term survival.

Our results show that wildebeest populations that no longer migrate are less genetically healthy than those that continue to migrate.

Because their populations aren’t mixing with other wildebeest groups, they are more inbred and genetically isolated. We expect this to lead to lower survival, reduced fertility and other debilitating health effects.

It isn’t just the wildebeest that’s threatened when we prevent them from migrating, but many other species as well. Wildebeest grazing keeps vegetation healthy and distributes nutrients. The wildebeest also serve as prey for predators, carrion for scavengers and their dung supports millions of dung beatles.

If the migrations are lost, Kenya and Tanzania risk losing an enormous amount of tourism revenue that benefits governments and local communities.

Collapsing populations

Our study is the first time that the genetic effect of migration in wildebeest has been studied.

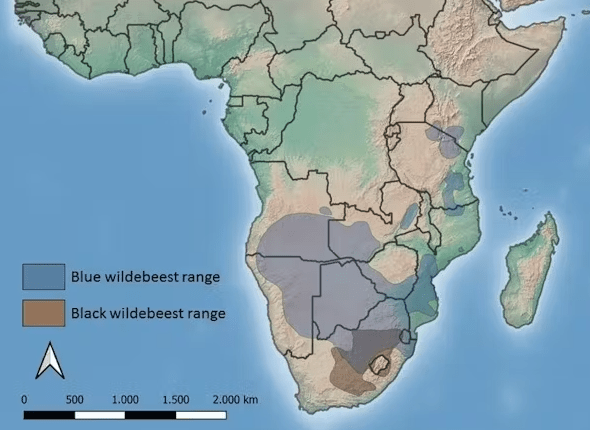

We analysed the genetic material of 121 blue wildebeest and 22 black wildebeest. We chose these 143 wildebeest from their entire range on the African continent, from South Africa to Kenya. This meant we were able to make a general genetic comparison between migratory and non-migratory populations.

Populations of migratory wildebeest showed greater genetic diversity. They had extensive random mating which reduced inbreeding levels compared to nearby populations whose migration patterns had been recently interrupted. This was found across multiple locations.

The conclusion is clear. There’s an overall negative genetic effect in wildebeest populations that have been prevented from migrating, regardless of where they live on the continent.

Reduced genetic diversity makes animals less healthy and therefore more vulnerable to illness and infertility. Populations with low genetic diversity are less able to evolve, or cope with changes to the environment. So, if climatic changes continue to intensify and there isn’t as much genetic variation to enable them to adapt, their survival could be threatened.

Already vulnerable

Large, non-migrating wildebeest populations are already vulnerable and their numbers shrink when they cannot migrate. This is because they don’t have enough food to eat, cannot access nutrient-rich calving grounds or don’t have enough drinking water in dry periods.

They also cannot escape their predators, become vulnerable to poaching and are vulnerable to disease outbreaks, like rinderpest.

While the total number of wildebeest across the continent remains fairly stable, many local migrating populations have experienced steep declines and several have even collapsed in recent decades.

We’ve seen this affect populations in parts of Kenya, Tanzania and Botswana.

For instance, the Mara-Loita migration collapsed by 76% from about 150,000 wildebeest in the 1970s to about 36,500 animals, all of which had become resident, by 2021.

And, in Botswana, fencing to protect cattle from coming into contact with migratory wild animals has seen the Kalahari wildebeest population decline by more than 94.2% from roughly 260,000 in the 1970s to fewer than 15,000 in the late 1980s.

These findings stress the critical need to preserve animal migration paths.

Putting things into perspective

Policymakers need to pay special attention to preserving the wildebeest’s old and natural migratory routes. There are certain steps that can be taken:

- protect highly variable arid and semi-arid lands inhabited by wildebeest

- protect critical drought refuges, such as swamps and woodlands

- regulate and strategically plan the expansion of permanent settlements, including urban centres, infrastructure, fences and cultivation in pastoral lands

- designate zones for wildlife and livestock grazing and settlements

- make and enforce clear rules and regulations governing land use, land sales, leases and development on crucial wildlife migration routes

- reintroduce locally endangered wildlife species, such as wildebeest, from outside ecosystems wherever possible.

By addressing these priorities, efforts to save and restore threatened ungulate mass migrations can be more focused, coordinated and effective, and contribute to the long-term conservation of these animals.

Joseph Ogutu is senior researcher and statistician at the University of Hohenheim. This article was first published by The Conversation.

Discussion about this post