Research from the Garvan Institute of Medical Research indicates that non-coding DNA, which comprises 98% of our genome and was previously considered “junk,” may play a crucial role in cancer diagnosis and treatment. The study found mutations in these regions that are linked to 12 different cancer types. These mutations occur in binding sites for the CTCF protein, which are vital for maintaining the genome’s 3D structure. Disruptions in these sites may contribute to cancer development. The findings suggest a potential universal approach to cancer treatment that targets these common mutations across various cancers.

Researchers at the Garvan Institute have utilized

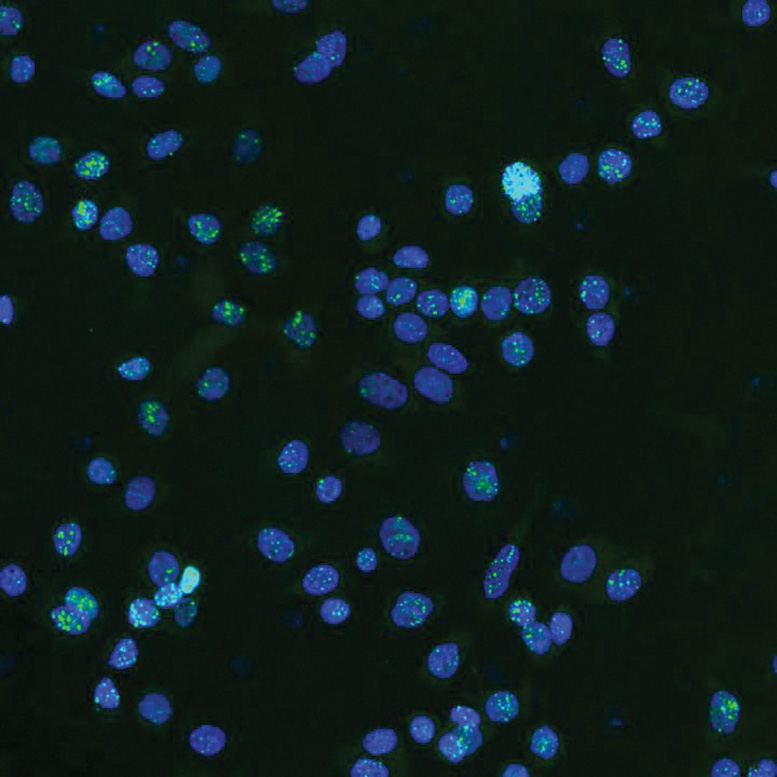

Visualized DNA damage (green) in human breast cancer cells (blue). Credit: Garvan Institute

Investigating DNA ‘anchors’ disrupted in cancer

The researchers focused on mutations affecting binding sites for a protein called CTCF, which helps fold long strands of DNA into specific shapes. In their previous work, they found that these binding sites bring distant parts of the DNA close together, forming 3D structures that control which genes are turned on or off.

“We had already identified a subset of CTCF binding sites that are ‘persistent’ – that is they act like anchors in the genome, present across different cell types,” says Dr Khoury. “We hypothesized that if these anchors become faulty, it could disrupt the normal 3D organization of the genome and contribute to cancer.”

To test this, the researchers developed a new sophisticated

Dr Amanda Khoury and Professor Susan Clark at the Garvan Institute of Medical Research in Sydney, Australia. Credit: Garvan Institute

“Using our machine learning tool, we identified persistent CTCF binding sites in 12 different cancer types,” says Dr Wenhan Chen, first author of the study. “Remarkably, we found that every cancer sample had at least one mutation in a persistent CTCF binding site.”

“This research confirmed that persistent CTCF binding sites are ‘mutational hotspots’ in cancers. We think these mutations give cancer cells a survival advantage, allowing them to proliferate and spread,” adds Dr Khoury.

Toward a universal cancer treatment approach

The findings could have broad implications for understanding and treating many types of cancer. “Most new cancer treatments have to be carefully targeted to specific mutations not always common amongst different tumor types, but because these CTCF anchors are mutated across multiple different cancer types, we’re opening up the possibility of developing approaches that could be effective for multiple cancers,” says Professor Susan Clark, Head of the Cancer Epigenetics Lab at Garvan and lead author of the study.

The researchers are now planning further large-scale experiments using CRISPR gene editing to investigate how these anchor mutations disrupt the 3D genome and potentially promote cancer growth.

“Now that we’ve discovered what we believe to be critical anchors of the genome and shown they are important to maintaining homeostasis of the genome architecture, it makes sense that these non-coding DNA mutations would disrupt this homeostasis in the cancer cell – a hypothesis we will test when we edit them out,” says Professor Clark. “Observing the downstream impact, we hope to identify key genes or gene pathways that are affected by the mutations, which could serve as markers for early cancer detection or targets for new treatments.”

“Finding these clues that were hidden in a vast amount of data is a powerful example of how artificial intelligence is boosting medical research,” she says. “This is a whole new frontier in the study of cancer, and we’re excited to explore it further.”

Reference: “Machine learning enables pan-cancer identification of mutational hotspots at persistent CTCF binding sites” by Wenhan Chen, Yi C Zeng, Joanna Achinger-Kawecka, Elyssa Campbell, Alicia K Jones, Alastair G Stewart, Amanda Khoury and Susan J Clark, 02 July 2024, Nucleic Acids Research.

DOI: 10.1093/nar/gkae530

This research was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Ideas grant and Investigator grant funding.

Discussion about this post