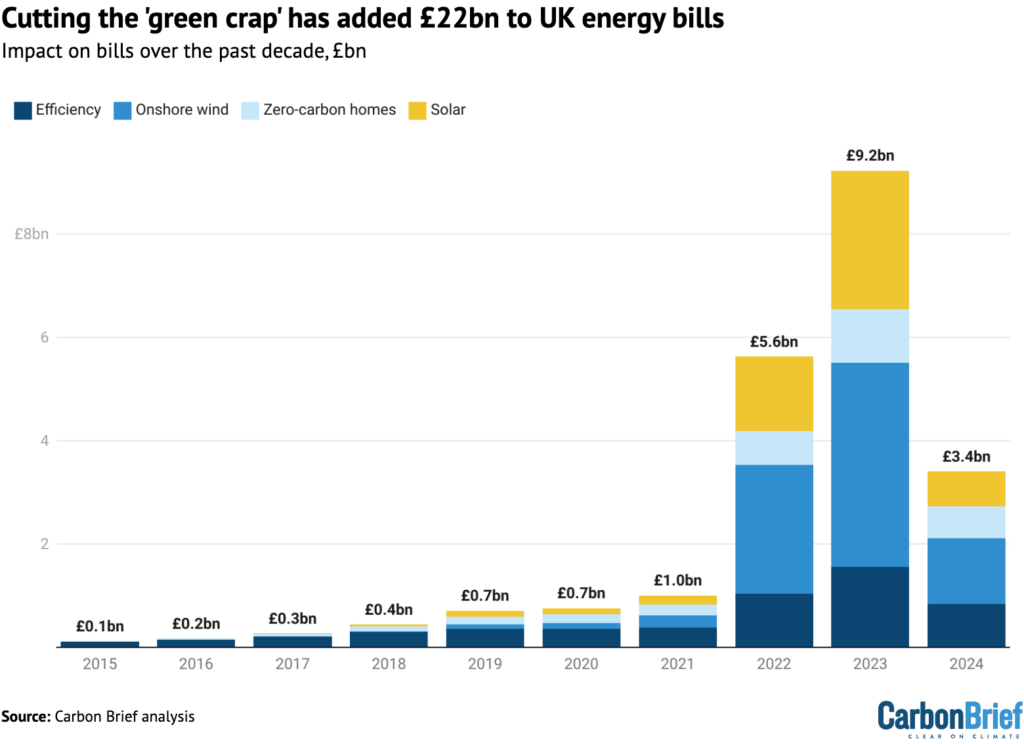

The UK’s energy bills were £22bn higher over the past decade than they would have been if Conservative governments had not cut “green crap” climate policies.

In 2013, then-prime minister David Cameron was infamously reported to have asked colleagues to “get rid of the green crap”, referring to climate policies supporting better home insulation.

His government later scrapped a “zero-carbon homes” (ZCH) standard for new-build homes, ended support for solar power and blocked the expansion of onshore wind.

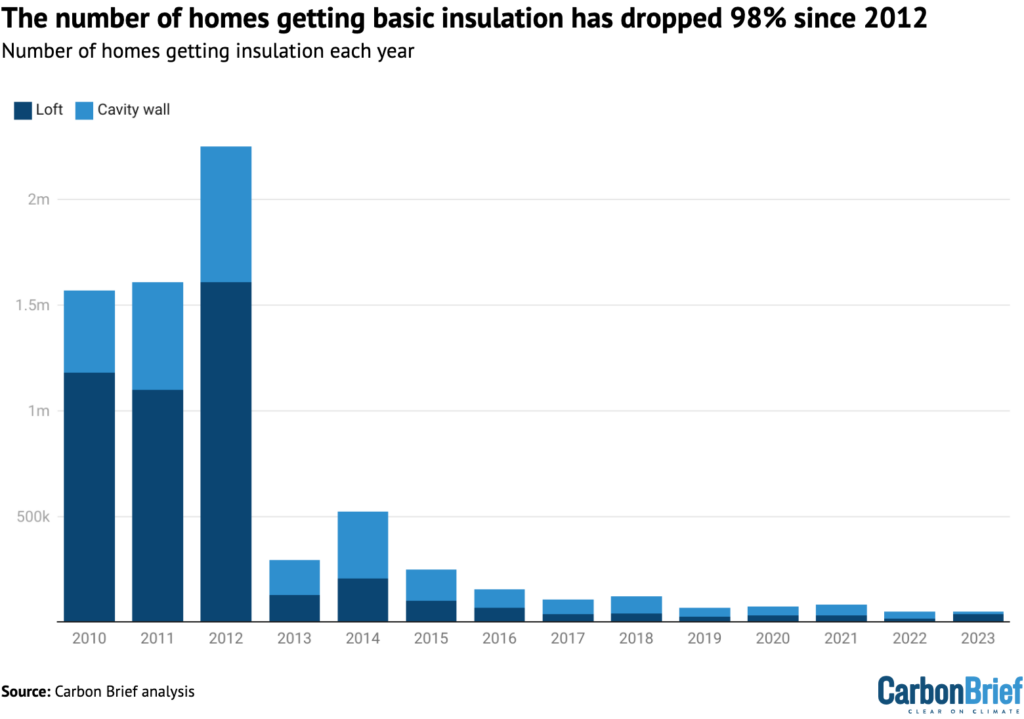

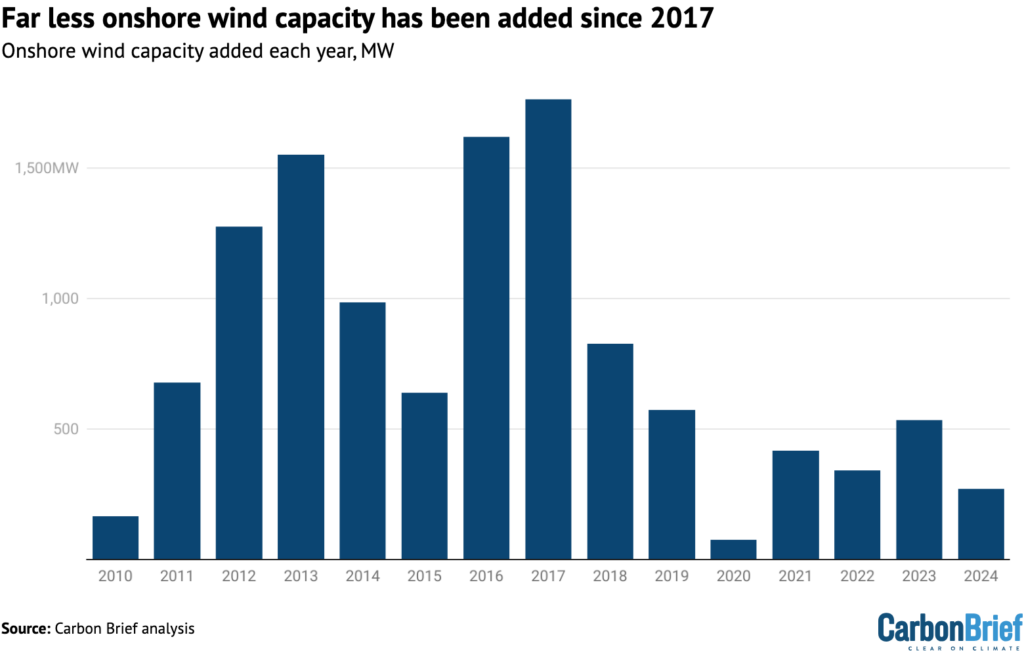

The number of homes getting insulated each year is now 98% below 2012 levels, while the growth of onshore wind and solar remains far below previous peaks.

Carbon Brief’s new analysis updates figures published in January 2022, showing that the “green crap” rollbacks left UK billpayers more exposed to record gas prices during the energy crisis.

The £22bn added to energy bills since 2015 as a result of the rollbacks includes £9bn due to not having built more cheap onshore wind, £5bn due to poorly insulated homes, £5bn due to low solar deployment and another £3bn because new homes were less efficient than the ZCH standard.

In total, the UK’s gas demand is 99 terawatt hours (TWh, 14%) higher than it would have been if climate measures had been added at earlier rates, the analysis shows. This means the UK’s net gas imports are 31% higher than they would have been with more “green crap” in place.

‘Green crap’ cuts

In November 2013, a Sun frontpage reported then-prime minister David Cameron’s “solution to soaring energy price[s]” with the headline: “Get rid of the green crap.”

Cameron’s government, in coalition with the Liberal Democrats, went on to make a series of changes, including cutting spending on energy-efficiency improvements and introducing the “green deal” efficiency scheme, later described by the National Audit Office as a “fail[ure]”.

The number of homes getting their lofts or cavity walls insulated each year plummeted almost immediately – by 92% and 74% in 2013, respectively – and has never recovered.

As of the latest figures for 2023, the number of homes getting these basic insulation measures each year is 98% lower than in 2012, as shown in the figure below.

If measures had continued to be added at the rate seen in 2012, an extra 7.9m lofts and 5.1m cavity walls would have been insulated by this year, leaving virtually no homes in the UK untreated.

In 2015, the Conservative administration then ended subsidies for onshore wind and introduced planning reforms in England that, together, were widely viewed as a “ban” on the technology.

Following a grace period for projects then already in the pipeline, the capacity of onshore windfarms being completed in the UK each year dropped dramatically after 2017, as shown below.

If onshore wind deployment had continued at the same rate as in 2017 then there would have been an extra 9.3 gigawatts (GW) of capacity by the end of this year.

Similarly, if solar deployment had continued at 2014 levels – which was well below the record rate in 2015 – then there would have been an extra 15GW in place by the end of this year.

Finally, the Conservative government in 2015 also scrapped the zero-carbon homes standard, which had been due to come into force the following year. As a result, around 1.6m new homes have been built since then with lower energy-efficiency standards – and higher energy bills.

Higher bills

The impact on bills depends on the cost of electricity and gas under the domestic price cap. The cap surged in 2022 after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and its decision to restrict gas flows to Europe.

While the price cap has fallen, it remains well above pre-crisis levels.

These changes are reflected in the figure below, which shows how much higher energy bills are as a result of having installed less insulation and fewer wind or solar parks.

Looking back over the past decade, getting rid of the “green crap” has added £22bn to UK bills, of which £19bn (84%) has come since the global energy crisis triggered by Russia.

In terms of gas demand, the UK’s less-well insulated homes now burn an extra 22TWh of gas each year, compared with what they would have needed if more “green crap” had been installed.

Similarly, the UK needs to burn an extra 77TWh of gas per year to generate electricity that would otherwise have come from additional onshore wind and solar capacity.

The estimated extra gas needed in 2024 – some 99TWh – is around 14% of the UK’s annual gas demand. Moreover, the additional demand due to getting rid of “green crap” means the UK’s net gas imports are 31% higher than they would have been, at 315TWh instead of 216TWh.

Methodology

Carbon Brief’s analysis of the impact of having got rid of the “green crap” is based on a series of assumptions about what would have happened if those policy measures had remained in place.

It aggregates the impact in terms of kilowatt hours (kWh) of gas that would have been saved by homes across the UK, relative to current domestic demand, as well as the amount and price of electricity that would have been generated from extra onshore wind or solar parks.

The analysis assumes loft and cavity wall insulation would have been added at the rate seen in 2012. Under this assumption, all remaining uninsulated lofts – and most cavity walls – would have been insulated by this year.

The analysis assumes that homes insulating their lofts or cavity walls would have reduced their gas usage from typical levels, by 6% or 12% respectively, based on analysis from University College London for the Climate Change Committee (CCC).

This gives similar figures, in terms of kilowatt hours (kWh) of gas saved, to the National Energy Efficiency Data-Framework (NEED), which reports the actual impact of home improvements in a sample of thousands of properties.

The analysis for the ZCH standard is based on figures for the actual energy use and floor area of new homes from the Home Builders Federation. This is compared with the recommended energy use per square metre under the standard, if it had been introduced.

Figures for energy use per home are combined with Office for National Statistics (ONS) figures on the number of homes built since 2016, when the standard was due to have come into effect.

The estimate for onshore wind assumes new capacity would have continued to be added at the same rate as in 2017, when 1.8GW was built. In total, this would have meant an extra 9.3GW being built by the end of 2024.

This capacity is assumed to have generated electricity at a load factor of 31% and cost of £46 per megawatt hour (MWh) in 2012 prices, based on a 2017 report from consultancy Baringa. The cost was converted to current prices using the Treasury GDP deflator.

(This is a conservative assumption for load factors. The UK fleet-wide onshore wind load factor is 26%, but newer wind turbines are larger and have higher load factors. The Department of Energy and Net Zero assumes new onshore windfarms have a load factor of 49%.)

The estimate for solar assumes new capacity would have continued to be added at the same rate as in 2014, when 2.6GW was built. This is below the peak year in 2015, when 4.1GW was added.

This would have meant an extra 15GW being built by the end of 2024. This capacity is assumed to have generated electricity at a load factor of 10% and at the same cost as onshore wind.

The energy savings and cheaper electricity that would have occurred with the “green crap” in place is converted to bill impacts in each year, based on the current and previous price cap levels, unit costs and implied wholesale electricity prices.

Sharelines from this story

Discussion about this post