The UK government could approve 13 new oil and gas projects in the North Sea, with the fuel produced emitting 350m tonnes of CO2 equivalent (MtCO2e) if burned, Carbon Brief analysis shows.

The Labour government, which took power last month, has ruled out issuing new oil and gas licences for the North Sea.

However, it has not ruled out approving projects that already have a licence, but have not yet received consent to begin development.

A former senior official tells Carbon Brief that the government may now be “compelled” to greenlight them due to the risk of legal action from oil and gas companies.

Official documents show that up to 13 such licenced projects are likely to seek development consent from the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ), led by Ed Miliband, and the North Sea Transition Authority (NSTA). Many of these projects could seek such consent within months.

The projects could collectively produce 858m barrels of oil equivalent. If all of this fuel was burned, it would produce 350MtCO2e, according to Carbon Brief analysis.

This is equivalent to the annual emissions of 111 of the world’s lowest-emitting countries, which have a combined population of 649 million.

A wide range of scientific evidence shows that new fossil-fuel projects globally are “incompatible” with the world’s ambition of limiting global warming to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels.

Since the landmark Horse Hill judgment in June, DESNZ will likely need to consider the emissions produced from burning fossil fuels when deciding whether to grant development consent to new projects for the first time.

A spokesperson for DESNZ chose not to comment on the 13 projects, instead reaffirming to Carbon Brief that the department “will not issue new licences to explore new fields”, but will not revoke existing licences.

What is the government’s stance on North Sea oil and gas?

The Labour party achieved a landslide victory in last month’s UK general election, with a campaign that promised major changes to the country’s climate and energy policies.

In its manifesto, Labour said it “will not issue new licences” for oil and gas, but that it “will not revoke existing licences”, leaving uncertainty around whether it will grant development consent to new projects that already have a licence.

The process for new North Sea oil and gas projects moving from obtaining a licence to reaching first production is complex, leading to a lot of confused reporting – with journalists often incorrectly describing Labour’s policy to end new licences as a “ban on new drilling”.

Under the previous Conservative government, multiple oil and gas licensing rounds took place.

Licensing rounds are carried out by the North Sea Transition Authority (NSTA), a company owned by DESNZ that acts as the UK’s oil and gas regulator.

(It is often pointed out that the NSTA is in the awkward position of being responsible for both ensuring the oil and gas sector reaches net-zero and maximising the economic recovery of oil from the North Sea.)

The most recent oil and gas licensing round took place from October 2022 to January 2023, leading to 82 licences being awarded to companies.

All of the licences awarded were production licences. This type of licence enables a company to explore for and then drill to extract oil and gas.

However, before they can set up operations and start drilling, they must obtain development consent from the NSTA, DESNZ and the Health and Safety Executive (HSE), the UK’s national regulator for workplace health and safety.

The “field development roadmap” below gives a sense of the various stages involved for a North Sea oil and gas project looking to obtain development consent.

The role of DESNZ in granting development consent for new oil and gas projects is highlighted in green.

Specifically, DESNZ is responsible for considering the environmental impact of a new oil and gas project.

As part of the environmental impact assessment, companies are asked to prepare an environmental statement, giving information on how the project could negatively affect the environment and what they plan to mitigate this. This could include, for example, how drilling activity could harm whales and dolphins living in the North Sea.

Until recently, when it came to the climate impact of their projects, companies only had to give information on the emissions caused by their operations. For example, from the energy used on oil rigs.

They did not have to provide DESNZ with data on the emissions that would be caused by burning the oil and gas they produce, which account for the vast majority of the emissions from a fossil-fuel project.

However, in June, the Supreme Court issued a landmark judgment ruling that all fossil-fuel projects seeking approval in the UK should provide decisionmakers with information on the emissions caused from burning the oil and gas that they plan to produce.

Delivering the majority judgment, Lord Leggett stated that the end use of any fossil-fuel extraction was always combustion, necessitating decisionmakers to take into account these emissions:

“The combustion emissions are manifestly not outwith the control of the site operators. They are entirely within their control. If no oil is extracted, no combustion emissions will occur.”

Lawyers tell Carbon Brief that the judgment means that North Sea oil and gas companies seeking development consent will now need to provide DESNZ with data on the emissions from burning the fuel extracted by their projects.

After considering the environmental impact of a project, DESNZ can either grant consent, request further information or refuse consent, if it considers the potential environmental impacts of the new project to be too large.

This decision, ultimately, lies with the secretary of state, Ed Miliband.

As noted above, Labour has not been clear on its position on development consent for new oil and gas projects that already have a licence.

Although DESNZ technically has the power to refuse new oil and gas projects on climate grounds, it might be difficult to do so in practice, says Adam Bell, head of policy at the consultancy group Stonehaven and former head of energy at the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (which has now been split into DESNZ and two other departments). He tells Carbon Brief:

“To say no, the secretary of state would need to demonstrate that the relevant project would indeed have significant environmental impacts. What ‘significant’ in this context means is very much up for grabs and the regulations do extend the secretary of state scope to refuse a project on climate impact grounds.

“However, such a contention would be difficult to stand up in court unless the secretary of state could demonstrate that the project would have a greater impact on the climate than an imports counterfactual. This would be challenging.”

Because of this, the government might be forced to greenlight oil and gas projects seeking approval, Bell says:

“My expectation is that unless the government takes the position that any further extraction anywhere globally increases the risk of climate change – with consequent impacts on international relations – they will be compelled to consent the projects.”

Commenting on the chance of the Horse Hill judgment making a difference, he adds:

“My expectation is that how emissions [from burning oil and gas] are considered will be crucial; whether purely on territorial grounds or in the context of global emissions.

“One can make the case for projects on the former, and the framework for doing so is, ironically, [the] Paris [Agreement] and nationally determined contributions. On the latter, it becomes much harder to consent to projects.”

(See: “What does this mean for efforts to tackle climate change?”)

Back to top

How much new oil and gas could be approved under Labour?

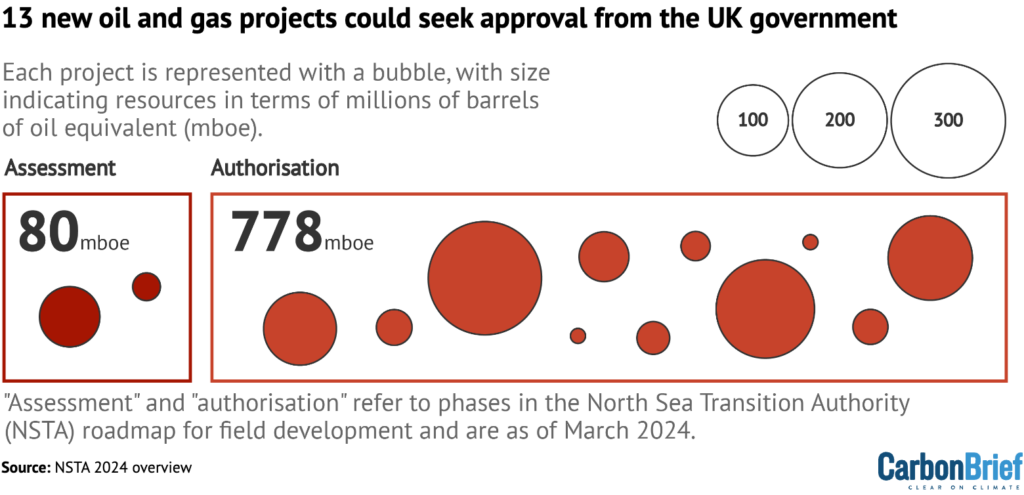

According to a 2024 overview from the NSTA, 13 new oil and gas projects are at a phase where they could soon be seeking development consent.

The NSTA says these projects would collectively produce 858m barrels of oil equivalent. When burned, this would produce around 350MtCO2e, Carbon Brief analysis shows.

The graphic below, which has been adapted from the NSTA’s overview, uses bubbles to indicate the relative size of the 13 projects that are likely to seek development consent, in terms of their oil and gas resources.

A spokesperson for the NSTA would not provide Carbon Brief with any further information on the projects represented in its overview, arguing this information is “commercially sensitive”.

However, Carbon Brief understands that some of the larger projects likely to seek development consent include the controversial Cambo oil project, the UK’s second-largest undeveloped oil and gas discovery in the North Sea, as well as the Buchan oil redevelopment project and the Avalon oilfield project.

Labour has previously publicly ruled out greenlighting the Cambo oil project – despite not ruling out approving other large oil and gas projects. (As noted above, it may be challenging for DESNZ to do this in practice.)

(Labour has also publicly pledged to stop the Rosebank oil and gas project, another large project that was approved for development by the previous Conservative government. The decision to approve Rosebank will face a legal challenge from environmental groups later this year.)

The NSTA spokesperson said that it is possible that not all of the 13 projects will “reach the stage” of seeking development consent. (A project with a licence may encounter economic or viability issues in its early stages.)

They added that “some may apply in the next few months”, while others will seek consent “over a longer time period”.

Back to top

What does this mean for efforts to tackle climate change?

There is a wide range of evidence to show that new fossil fuel projects globally could blow efforts to limit global temperature rise to 1.5C, the aspiration of the Paris Agreement.

A scientific review of all known feasible routes for keeping to 1.5C published in 2022 concluded that developing new oil and gas fields is “incompatible” with the target.

It followed on from a landmark road map to net-zero released by the International Energy Agency in 2021, which said there are “no new oil and gas fields approved for development in our [1.5C] pathway”.

(In 2023, the IEA updated its wording to say that “no new long lead time conventional oil and gas projects are approved for development” in its 1.5C pathway.)

The latest UN Emissions Gap Report in 2023 said that the coal, oil and gas extracted over the lifetime of producing and under-construction mines and fields as of 2018 “would emit more than 3.5 times the carbon budget available to limit warming to 1.5C with 50% probability, and almost the size of the budget available for 2C with 67% probability”.

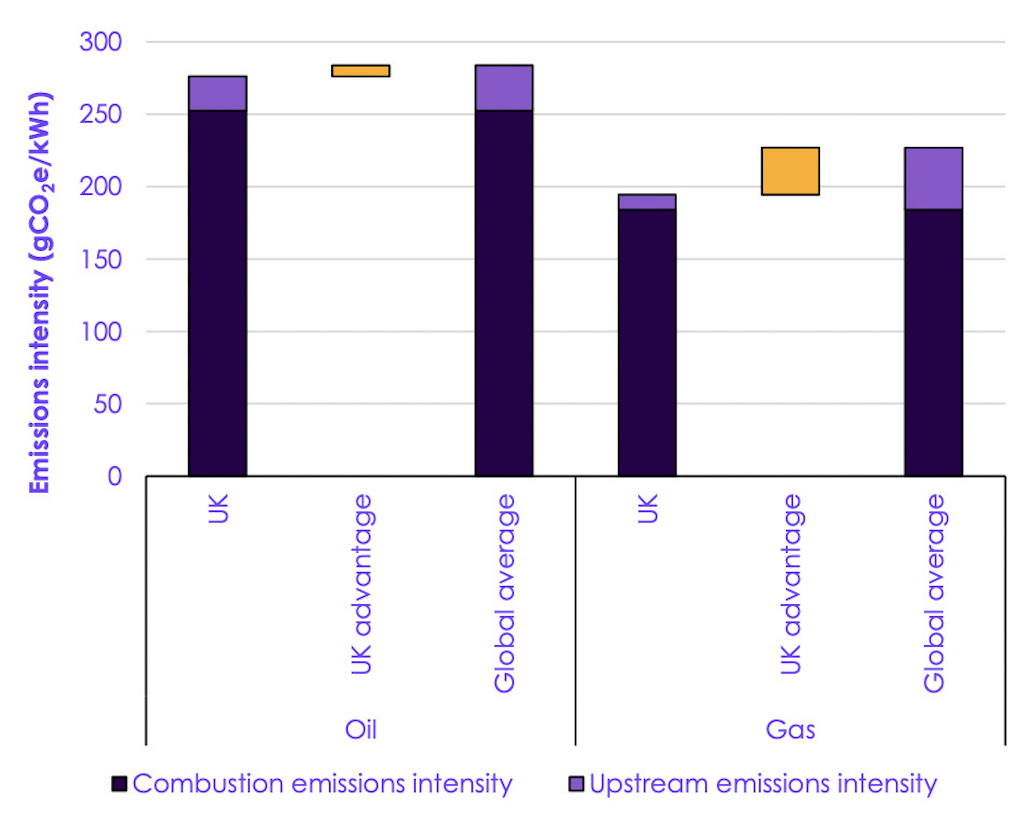

While the scientific case against new fossil fuel expansion is clear, North Sea advocates sometimes argue that the extraction of oil and gas in the UK has lower emissions than the global average and, therefore, offers an advantage.

In 2022, the UK’s climate advisers, the Climate Change Committee, published an analysis examining whether there is currently any climate benefit to using oil and gas produced in the UK, rather than that imported from overseas.

It found that the emissions intensity of oil and gas produced in the UK is lower than the global average, suggesting there may be a small “advantage” to domestic production.

But, although the UK has a climate “advantage” in terms of emissions during production when compared to the global average, it is not outperforming Norway, the country from which it currently sources most of its oil and gas imports.

An analysis published in 2022 found that, on average, UK production in the North Sea was nearly three times more emissions intensive than Norwegian production.

Furthermore, potential small climate “gains” from using domestic oil and gas over imports could be undermined because extracting more fossil fuels could impact global demand.

Namely, if the UK produces more oil and gas, it could contribute to falling prices and, thus, rising demand, fuelling more use and higher emissions.

Previous CCC analysis found that, even if every 100 units of new UK gas production only adds 14 units to global gas demand overall, the upstream emissions advantage would be wiped out by higher usage elsewhere.

Similarly, it concluded that the upstream emissions advantage for oil would be wiped out even if every 100 units of new oil production only added three units to global oil demand.

It is also worth noting that oil and gas produced in UK waters is sold to the global market and does not “belong” to the UK.

Around 80% of oil produced in UK waters is currently exported. Similarly, during the global energy crisis, UK gas exports soared.

The 13 projects looking to obtain development consent would produce 858m barrels of oil equivalent, the NSTA says. This is equal to around two years of UK oil and gas production at current levels.

However, the North Sea is already in decline. Oil production peaked in 1999, while gas production in the UK continental shelf peaked in 2000.

The journey to net-zero will see petrol and diesel cars replaced by electric cars, fossil-fuel boilers replaced by heat pumps and gas power stations replaced with low-carbon alternatives, such as renewables, nuclear and storage. All of this will see oil and gas demand plummet over the coming decades.

This means that new oil and gas will not do much to boost UK energy security – something noted by DESNZ. Referring specifically to oil and gas licences, a spokesperson tells Carbon Brief:

“We will not issue new licences to explore new fields because they will not take a penny off bills, cannot make us energy secure and will only accelerate the worsening climate crisis.”

Prime minister Keir Starmer has previously said that restoring the UK’s reputation as a climate leader is a key priority for his government.

Committing to stopping all new oil and gas projects, rather than just ending new licensing rounds, could give a boost to these efforts, says Tessa Khan, an environmental lawyer and executive director of Uplift, the North Sea oil and gas transition campaign group. She tells Carbon Brief:

“Signalling an end to new oil and gas exploration will be a significant step forward in restoring the UK’s reputation as a climate leader. However, to really bring the UK into alignment with climate science, it needs to go even further and reject any new oil and gas developments – not just licences.”

She adds that setting a clear plan for ending new oil and gas projects – rather than leaving uncertainty over new projects – could help the sector prepare for a just transition:

“Clarity about the future of the oil and gas sector will help to plan a responsible transition that protects the workers and communities that have ties to the industry. If the UK takes these steps, it can set a real example of climate leadership.”

Back to top

CO2 emissions calculations by Verner Viisainen and Simon Evans.

Sharelines from this story

Discussion about this post