Rivers, like mountains, are places of the imagination as much as they are facts of geography and political history.

In the introduction to his 2014 book Congo: The Epic History of a People, Belgian historian David van Reybrouck acknowledges this duality — let’s call it the magical actuality of rivers — in relation to Central Africa’s greatest river.

The Congo, tells Van Reybrouck, has a resonance that far exceeds its 4 700km length. The basin where the river flows into the Atlantic Ocean is an enigma of colour: a yellowish, ochre, rusty broth, he writes, that stretches westward for 800km during the rainy months: “That is how a country begins: far before the coastline, thinned down with lots and lots of seawater.”

Curator Owen Martin was still living in Cape Town — a place of epic mountains but meh rivers — when he read Van Reybrouck’s widely admired book. He found the connections the author made between hydrology and history insightful and banked them for a possible exhibition about rivers.

It took river time and a change in address to ultimately realise that exhibition.

Martin lives in Oslo, Norway, where he is a curator at the Astrup Fearnley Museum.

Two years into his new role at the resourced private art museum with extensive holdings of blue-chip American and European artists, Martin has finally realised his dream exhibition. Its realisation is partly a story of revival.

Among South Africans, Martin is best known from his five-year tenure as the likeable chief curator of Cape Town’s Norval Foundation.

After joining Norval from Zeitz MOCAA in 2017, Martin excelled at organising solo exhibitions spotlighting major African talents, among them Kenyan painter Michael Armitage and Ghanaian installation artist Ibrahim Mahama.

But the departure of Norval CEO Elana Brundyn in 2022 saddled Martin, a Canadian who came into the orbit of art collector Jochen Zeitz in 2011, with new administrative duties. He often looked beleaguered. Early last year, Martin ditched Cape Town for a new job in Oslo.

Between Rivers is Martin’s first major thematic exhibition.

Group exhibitions are how aspiring curators signal their ambition. During his time at Norval, such statement exhibitions were the province of curators such as Karel Nel and Portia Malatjie. But now, on the cusp of turning 40, Martin is finally making his play.

Between Rivers is a thoughtful, literary-influenced exhibition that, while at times recondite is, ultimately, stimulating — even renewing this old hack’s sense of South African history.

The first notable thing perhaps is the title. Van Reybrouck may have suggested an idea to Martin, but it was the Kenyan author Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s 1965 novel The River Between that inspired his exhibition’s title.

The Norwegian geographer Terje Tvedt, whose non-fiction book The Nile (2021) is both a sweeping history and travel narrative of the world’s longest river, further expanded Martin’s thinking.

The guide introducing the exhibition is prefaced by a quote from a 2022 essay by Canadian poet and writer Lisa Robertson. “A flood is what flows says the etymology, where the flowing is in excess,” it reads. “But it is by flooding that a river constructs its form; form is the remnant of excess, the despair of content, the failure of escape.”

The epic floodplain of the Congo River is visual evidence of this particular river’s geometry. Differently put, the river becomes the sea, but the sea is also the memory of a river.

Between Rivers gathers works by 12 artists whose work is engaged in “representing a subject that is at once fixed and relentlessly in motion”, as Martin phrases it in the exhibition guide.

His line-up pushes against his employer’s masculine, Euro-American collecting focus, favouring instead a worldlier, gender-sensitive roster of participants.

To be sure, the exhibition includes major American artists such as Zoe Leonard and Senga Nengudi, as well as respected Europeans like Alex Ayed, Marjetica Potrc and Cato Løland — the only Norwegian on it. But Between Rivers also includes works by artists from Columbia, Egypt, India, Morocco, Pakistan, South Africa and Vietnam.

Water often mediates identity; it has the capacity to erase it, too. The Franco-Tunisian artist Alex Ayed has embraced the liberating potential of water. Last year, Ayed set off on a multi-year, round-the-world sailing expedition. His new aquatic identity was heralded with an exhibition.

“In contemporary societies, contemplation — of clouds, the wind, a bird flying overhead, other sensory observations — seems to be only for the dreamer, but in reality, it is what is most essential for anyone living at sea,” Ayed explained in a statement prefacing last year’s exhibition at Paris’s Louis Vuitton Foundation.

“These elements, which on land would be described as ‘poetic’, are vital for the sailor … [enabling them] to live in an environment that is as hostile as it is sublime.”

Martin’s exhibition probes this duality, juxtaposing works that explicitly invoke rivers as social entities with works that favour more “oblique strategies”, to borrow an expression from musician and artist Brian Eno.

The exhibition opens with excerpts from Zoe Leonard’s Al río / To the River (2016 to 2022), a photo essay depicting aspects of life along the Rio Grande. The river demarcates the US’s contentious border with Mexico, where it is known as Río Bravo.

Leonard’s black-and-white photos are repetitive and matter of fact. Six photos record pleasure seekers gathered at a manmade place along a stretch of the river not dissimilar to the industrialised rusticity of the Limpopo at Beit Bridge. A grid of 34 photographs shows a helicopter surveilling something or someone.

The exhibition shortly jettisons this social approach in favour of works that “harness the poetic and imaginative possibilities” of rivers.

The wood-and-rope structure at the centre of Slovenian artist Marjetica Potrc’s installation is a prompt to consider novel “Earth jurisprudence”, which argues for extending legal rights to natural entities such as rivers.

The House of Agreement Between Humans and Earth, as Potrc’s work is titled, was made in collaboration with Ray Woods, an Aboriginal elder, for the 23rd Biennale of Sydney in 2022. Earth jurisprudence has a strong foothold in Australia.

Potrc’s work is among a handful on the show with pre-approved status.

Moroccan artist Hicham Berrada’s Mesk-ellil (2019), seven tinted-glass terrariums housing growing examples of night-blooming jasmine, was shown at collector François Pinault’s private museum in Venice, Punta della Dogana, in 2019.

Ditto the Indian artist Reena Saini Kallat, whose trio of sound sculptures, Chorus I-III (2015 to 2019), appeared in the 15th Sharjah Biennial in the United Arab Emirates.

Kallat’s remarkable and joyous works revive the form of pre-radar listening devices used in earlier 20th-century military surveillance. Each emits a cacophony of birdcalls linked to avian species inhabiting tumultuous border zones: Israel-Palestine, Ireland-UK and Mexico-US.

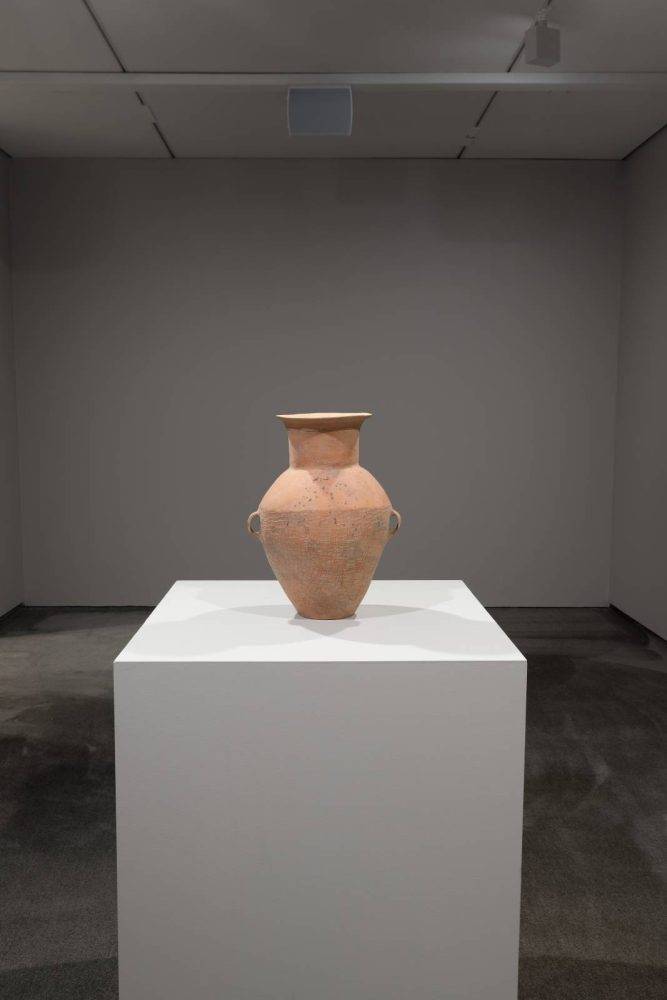

The invocation of sound as art material is also central to James Webb’s contribution to Between Rivers. “What were you made to contain?” asks voice artist Lesoko Seabe of a 4 000-year-old Neolithic clay vessel from the Upper Yellow River region of China installed on a plinth and shown alone in a carpeted room. More questions follow. “What experiences do your scars speak of?”

The questions, numbering 172, were drafted by Webb, a Cape Town artist now living in Stockholm, Sweden. Cumulatively, the questions invite the viewer-listener to consider the various possible social and cultural meanings and resonances of the object being confronted.

In June, Webb staged a similar work in Basel, Switzerland. An outdoor speaker installed on the historic Mittlere Brücke (Middle Bridge) over the Rhine played a series of probing questions voiced by Victoria Davies.

Webb’s work is one of two notable new commissions for Martin’s show. The other is a triangular tunnel built into an interior wall of the museum.

“Danger lurks in darkness,” says a character in Ngugi’s The River Between.

The Columbian artist Delcy Morelos flirts with this idea in her cinnamon-and-clove-scented grotto piece Profundis (2024). You smell the work before you see it, which is barely, its dark interior unlit.

The piece incorporates soil harvested from the Glomma, Norway’s longest river.

The river was once used to float felled trees to market.

There is an oblique South African connection — Norwegian timber was a staple for the enormous Dutch cargo ships of the 16th and 17th centuries, some of which plied the route around the Cape.

The sea is a recurrent cipher in Martin’s exhibition about rivers. It is most explicitly signalled in a sampling of Ayed’s tricksy practice. Martin has included four of Ayed’s painting-like things made from sailboat fabrics, as well as an unregistered emergency position-indicating radio beacon, an insect preserved in olive oil and a taxidermied seagull.

The abstract paintings, austere yet visually tactile, each compel. They are profitably shown together with the largest of Nengudi’s four water sculptures.

Part of a cohort of talented California artists to emerge in the later Sixties, Nengudi is the original slay queen — and also spirit mother of export-quality South African artists like Dineo Seshee Bopape and Turiya Magadlela.

Shunning the agit-prop Civil Rights art produced by her peers, Nengudi favoured object-related performance and bold sculptural experimentation. Her earliest resolved works involved trapping water dyed with food colouring in heat-sealed vinyl forms.

Started in the late Sixties and inspired by a year spent studying in Japan, Nengudi stopped making these ephemeral, and sometimes participatory, works after the introduction of the commercial waterbed in the early Seventies.

Although reconstructions of the lost originals, Nengudi’s “water compositions” are nevertheless the oldest works on show. They operate as a kind of ballast, transforming water — that key ingredient of rivers — into a magical actuality, present, trapped but still potent.

![Ep265: [Lean Series] 5 Ways You’re F*cking Up Your Fat Loss Ep265: [Lean Series] 5 Ways You’re F*cking Up Your Fat Loss](https://carrotsncake.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/IMG_3025-768x1024-1.jpg)

.png)

Discussion about this post