| Dear Readers: Before we begin today, we wanted to share an offer from our friend Taegan Goddard, who runs Political Wire. Crystal Ball readers can get 20% off a site membership using this link. We highly recommend the site as a place to catch up on the latest political news.

Today’s Crystal Ball features the latest edition of Notes on the State of Politics, with a couple of shorter items: Kyle Kondik argues that his home state of Ohio shouldn’t be looked at as a key presidential battleground despite what amounted to a big Democratic victory in a recent statewide ballot issue, and Carah Ong Whaley sounds an alarm about the threat that a newly-emerging campaign tool, Generative AI, poses amidst a campaign landscape already littered with disinformation. — The Editors |

Don’t expect Ohio to be a 2024 battleground

In the aftermath of Ohio voters strongly rejecting an effort by state Republicans to make it harder for voters to amend the state constitution, there has been a little bit of buzz about Ohio potentially returning to the 2024 presidential battlefield. Back in 2016, I wrote a book about Ohio’s longstanding bellwether status titled The Bellwether. For decades prior to that election, no state voted more often for the presidential winner, and no state more consistently reflected the national popular vote than Ohio. But the 2016 election saw a national political realignment that pushed much of the Industrial North toward the Republicans. This had the effect of ending Ohio’s bellwether reputation — and the Issue 1 vote does not change that.

In a piece for Politico Magazine published earlier this week, I argued that Ohio should not be looked at as a key battleground in 2024. For starters, the Issue 1 vote is inherently different than an actual partisan election, because Democratic issue positions can be more popular than Democratic candidates, as I wrote in the piece:

“In 2018, we saw a similar phenomenon when Missouri voters approved a minimum wage ballot issue by 25 points in the same election that they backed now-Republican Sen. Josh Hawley over then-Democratic incumbent Claire McCaskill by 6 points. Just last year, Kentuckians voted with the pro-abortion rights side, declining by about 5 points to specify that the Kentucky Constitution does not contain abortion rights protections. In the same election, they reelected Republican Sen. Rand Paul by 24 points. Be careful about extrapolating trends from an off-year ballot issue vote in Ohio to next year’s general election.”

As we noted in the Crystal Ball when analyzing the Issue 1 vote, the Democratic position performed relatively well compared to recent partisan results in many of the so-called “collar counties” that surround the state’s three big urban counties, Cuyahoga (Cleveland), Franklin (Columbus), and Hamilton (Cincinnati). But the partisan results, where Democrats did much worse, are more germane to future partisan elections, and there just aren’t many positive indicators for Democrats in those places compared to some other collar counties in other states (defined as suburban/exurban counties that share a county border with a major urban county). Quoting again from the Politico column:

“Amid the larger, pro-Republican trends in the Industrial North, there has been some pro-Democratic movement in the region’s collar counties — movement that was vital in Joe Biden’s efforts to reclaim some of these states in 2020. For instance, some of the still-red Milwaukee collar counties — Waukesha and Ozaukee, two of the state’s three so-called WOW counties — both saw their GOP presidential margins drop double-digits from 2012 to 2020. In Michigan, the Detroit satellites of Oakland and Washtenaw counties got bluer, and in southeast Pennsylvania, the Democratic margin in Philadelphia’s northwest neighbor, Montgomery County, nearly doubled. Overall, the trade-offs were still good for Trump in this region, but his erosion from Mitt Romney’s performance in some key suburban places contributed to his narrow losses in the old ‘Blue Wall’ in 2020.

“In Ohio, however, it’s much harder to find examples of Democratic growth in these kinds of suburban/exurban collar counties: 12 of the 15 that touch Cuyahoga, Franklin or Hamilton got redder from 2012 to 2020.”

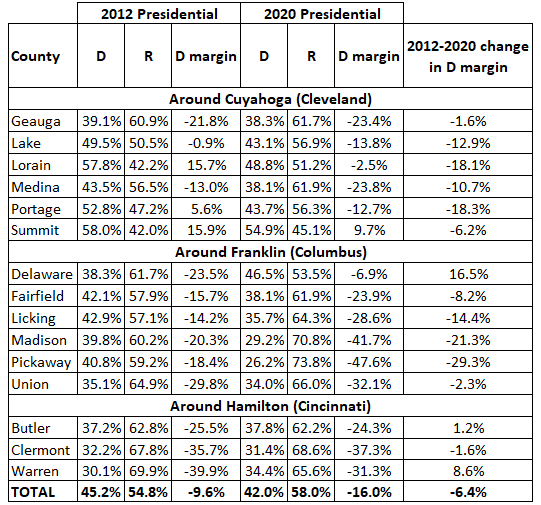

Table 1 lays out these 15 collar counties in Ohio, which together made up a little more than a quarter of the total two-party vote in Ohio in 2020:

Table 1 and Map 1: 2012 vs. 2020 in Ohio “collar counties”

Note: Table and map use the two-party presidential vote from 2012 and 2020

Source: Dave Leip’s Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections

As the table makes clear, most of these counties became more Republican from 2012 to 2020. The exceptions were Delaware just north of Columbus, as well as Butler and Warren, which are north of Cincinnati. But as the table shows, even though there has been an erosion in GOP support in these places — particularly in Delaware, which is Ohio’s most educated county based on four-year college attainment — these counties are still Republican (and the two around Cincinnati are really Republican). It is true that these collar counties shifted less toward Republicans, collectively, than the state did from 2012 to 2020 (6.4 points in margin compared to 11.0 statewide), but the Democrats really need to make up ground in these places to offset bigger losses in the areas further away from the urban centers.

Coming up in November, Ohio voters are going to weigh in on a ballot issue that would embed strong abortion rights protections into the state constitution as well as a ballot initiative (that is not a constitutional amendment) that would legalize recreational marijuana. We can imagine both passing and, in the aftermath, more chatter about whether Ohio, the longtime bellwether, was once again moving to the center of American presidential politics. But we don’t really buy it, as the actual partisan trends — the trends that show enduring strength for Republicans statewide — are just more important than ballot issue results in assessing the 2024 battleground.

How generative AI tools can make campaign messages even more deceptive

Winter is coming. We are rapidly moving from “alternative facts” to artificial ones in politics, campaigns, and elections.

In July, a campaign ad from Never Back Down, a group that supports Gov. Ron DeSantis (R-FL) in the 2024 presidential race, attacked former President Trump. The ad featured a soundbite of what sounds like former President Trump’s voice. But it wasn’t. Generative Artificial Intelligence (Gen AI) is a tool that is used by humans, but it poses several dangers to elections and to democracy. Leading into the 2024 election, we are already seeing the use of “deepfakes,” computer-created manipulation of a person’s voice or likeness using machine learning to create content that appears real. We spoke with UVA Today about the challenges deepfakes pose to free elections and democracy, and we are sharing some key points that we made in the piece:

Candidate comments out of context, and doctored photos and video footage, have already been used for decades in campaigns. What Gen AI tools do is dramatically increase the ability and scale to spread false information and propaganda, leaving us numb and questioning everything we see and hear at a time when elections are already facing a crisis of public confidence. Such tools also open up the ability to spread mis-, dis-, and malinformation to any person in the world with a digital device. On top of that, depending on how Gen AI tools have been trained, they can amplify, reinforce, and perpetuate existing biases, with impacts on decision-making and outcomes.

One of the biggest challenges is that political consultants, campaigns, candidates, and even members of the general public are forging ahead in using the technology without fully understanding how it works, nor, more importantly, all of the potential harms it can cause.

For some voters, exposure to certain messages might suppress turnout. For others, even worse, it could stoke anger and political violence. It’s worth noting here it’s not just the United States having elections in 2024 — there are some 65 elections across 54 countries slated for 2024. So, the potential harms extend globally. I am especially concerned about the use of AI for voter manipulation, not just through deepfakes, but through the ability of Gen AI to be microtargeting on steroids through text message and email campaigns. Indeed, Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI, stated in testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee that spreading one-on-one interactive disinformation was one of his greatest concerns about the technology.

With significant changeover in leadership at social media companies, especially at X (formerly Twitter), policy and technical teams may not be fully prepared to detect, assess, and prevent the proliferation of mis-, dis-, and malinformation across platforms. This is particularly troubling given that malinformation online and organizing online can spill over into political violence in the real world. Think Charlottesville 2017 or Jan. 6, 2021 at the U.S. Capitol, but much, much worse.

In the United States, Congress and the White House are deliberating how to balance the harms and advantages of Gen AI, but more needs to be done now to address the harms as we head into the 2024 elections. Seven leading tech companies — Amazon, Anthropic, Google, Inflection, Meta, Microsoft, and OpenAI — recently signed a voluntary commitment with the Biden administration to manage risks created by AI. Among the commitments, companies promised to develop “robust technical mechanisms to ensure that users know when content is AI generated, such as a watermarking system.” This is a much-needed step, but questions remain about whether those companies (and others) can uphold their commitments and whether users just could work around technical mechanisms.

In order to combat the challenges posed by AI-generated political messages, the lowest-hanging fruit would be to require candidates, campaigns and PACs, issue groups, etc. to report the use of Gen AI, in the same way they are required to report campaign expenditures or lobbying activities. Candidates and campaigns should also be required to clearly label not just videos, but also emails and text messages microtargeting different demographic groups. Ideally, there would also be a repository for election materials and messages so we can research and have a better understanding of who is sending what to whom, and the impacts of Gen AI’s use.

While we wait on a much-needed regulatory regime, the Federal Election Commission is also debating what powers it may have. The FEC has opened up public comment on whether it should amend regulations to include deceptively Artificial Intelligence in campaign ads. Comments will be accepted until Oct. 16, 2023.

The Center for Politics will be tracking the developments related to the use of AI in campaigns and elections. If you have a tip or suggestion, email me at clo3s@virginia.edu.

Learn more about AI on the following episodes of our Politics Is Everything podcast: A Regulatory Regime for AI? ft. Congresswoman Yvette Clarke; Neverending Cat and Mouse: Are Online Companies Prepared for 2024 Elections? ft. Katie Harbath; Saving Democracy from & with AI ft. Nathan Sanders; and How Congress Is Addressing the Harmful Effects of AI ft. Anna Lenhart.

Read more in the UVA Today article by Bryan McKenzie: “Is That Real? Deepfakes Could Post Danger to Free Elections”

Discussion about this post