As Australia seeks to reduce emissions, and as international tensions highlight the country’s reliance on volatile trade relationships, experts say the mining sector has a pivotal role to play in securing a self-sufficient, greener nation.

Key points:

- Australia holds the third largest amount of vanadium in the world, yet doesn’t produce any

- International tensions, a focus of renewable energy, and overpopulation are factors driving up demand

- Australia has an “enormous” opportunity to supply the world with the “new-economy mineral”

It is vanadium mining that has got industry experts excited.

The hard, metallic element is used in redox flow batteries that store grid-scale energy and are often attached to power plants or electrical grids.

Vanadium is also used with steel to produce lighter, stronger, and more resistant building materials.

Behind China and Russia, Australia holds the third-largest amount of vanadium in the world.

But until now there have never been plans to dig it out of the ground.

“With current geopolitical factors, some countries are realising that it’s not in their best interests to be sourcing such an important product from China and Russia,” said industry analyst of 30 years Professor Rick Valenta.

“Not only that, as countries are having to build more to accommodate rising populations, demand for metals like vanadium will surge.”

Australian-made metal for global renewables race

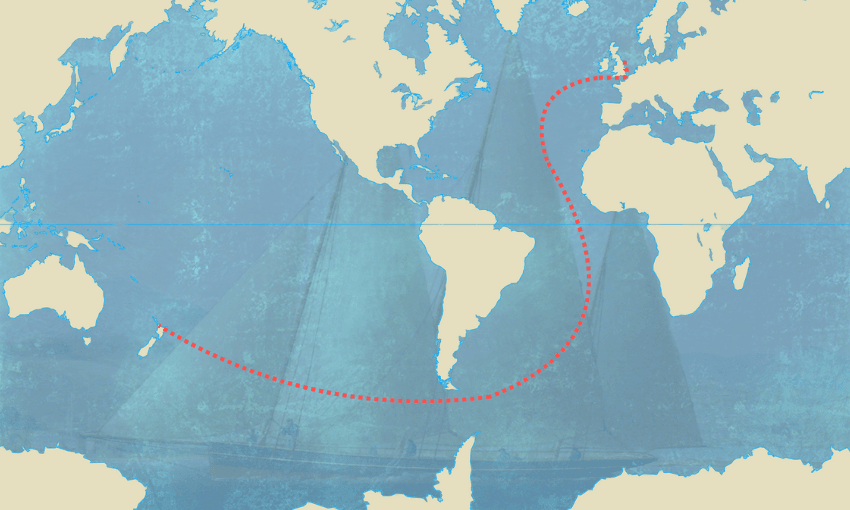

Currently, there are seven vanadium mines in pre-operation phases around the country — four in Western Australia, two in north-west Queensland, and one in the Northern Territory.

Many are predicted to start mining within the next year or two and, with two on-shore processing plants in proximity to the mines, proponents say jobs and capital will be retained in Australia.

“We see this area as an enormous opportunity, not only to be self-sufficient in Australia but compete on the world stage for vanadium as a critical, new-economy mineral,” said Jon Price, managing director of Horizon Metals.

The company’s Lilyvale project in Richmond, in Queensland’s North West Minerals Province, is set to begin operating in less than a year.

“We want a strong downstream flow of production here in Australia and we want battery manufacturers to be building here in Australia to get that self-sufficiency.”

In response to the launch of Horizon Metal’s Richmond mine and the nearby Julia Creek Multicom Resources project, the Queensland government committed $10 million to construct a processing plant in Townsville.

“Make no mistake, the resources revolution is coming,” said Queensland Minister for Trade and Investment, Cameron Dick, back in November when the plant was announced.

Not just renewables

While only a small percentage of vanadium is used for batteries at the moment, Professor Valenta said the global shift toward renewables would trigger a surge in demand.

“Only about 2 per cent of vanadium produced around the world is used for redox flow batteries,” he said.

“But they’re such appealing batteries, demand will increase.

“They can last for over 20 years, they don’t degrade over time, and they don’t catch on fire, which is a major problem for other large-scale batteries.”

The Queensland government projected demand for vanadium redox flow batteries would grow “exponentially over the next decade”.

But it is not just renewables that are driving the focus on vanadium.

As the global population climbs, so too does the demand for metals to expand the cities and vehicles that accommodate such growth.

Professor Valenta said 90 per cent of the vanadium that we consume goes into steel.

“As overpopulation becomes a global issue, that puts pressure on more traditional metal resources like iron, titanium, et cetera,” he said.

Professor Valenta said he was confident the increasing demand for vanadium, coupled with the fractured global political climate, would see international heads turn to Australia.

“And that’s where Australia has a great opportunity to show the world we can supply a safe, clean, competitive resource.”

Discussion about this post