This month, Sonja Bernhard is giving up the full-time nursing career she’s held for 14 years.

The St. Joseph’s Healthcare Hamilton nurse says chronic understaffing, limited resources, constant overtime and poor pay, fuelled by surging rates of the COVID-19 Omicron variant, led her to take a part-time role, which she’ll supplement with another job that pays $6 less per hour.

Despite knowing the profession needs her now more than ever, she says she simply cannot work under such “dangerous” conditions any longer.

“I’m tired, done, finished, mentally checked out. I am 100 per cent burnt out,” Bernhard says.

Advocates for the nursing sector are sounding the alarm of an impending “public health crisis” as burnt-out workers like Bernhard take a step back from the profession, or contemplate leaving the sector altogether, as surging rates of Omicron across the country stretch already limited staff to breaking point.

“When you add these things together, you get a recipe for a level of burnout which is well beyond anything that we’ve ever experienced. And it will manifest itself in people leaving in significant numbers,” says Michael Hurley, president of the Ontario Council of Hospital Unions.

“This is the public health crisis that we’re not talking about.”

Omicron pushes nurses to breaking point

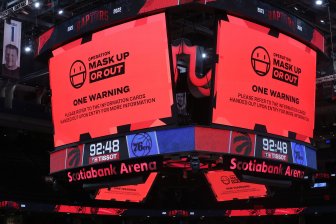

The warning comes as Ontario Premier Doug Ford this week announced several new COVID-19 public health measures, including moving schools online and enacting restaurant and gym closures and capacity limits as the province struggles to contain the spread of Omicron.

Two hospitals in the Greater Toronto Area are moving to a “code orange” to address an increase in COVID-19 patients and staffing shortages, which will see staff redeployed and some patients transferred to neighbouring hospitals to help free up capacity.

Read more:

GTA hospitals call ‘code orange’ to help address Omicron-fuelled COVID-19 surge

As of Wednesday, 2,081 Ontarians were in hospital with COVID-19 and 288 were in ICU.

The province reported another day of soaring positive cases, with 11,582 confirmed – the total is not a true representation of actual infections as testing across the province has been restricted to those in high-risk groups.

While Canada’s nursing shortage pre-dates the pandemic, workers and experts say the past two years have exacerbated issues that have repeatedly failed to be addressed, including an aging workforce, poor salaries and the pull of higher-paying international jobs.

In 2020, Ontario had the lowest nurse-per-capita ratio in Canada, with 665 registered nurses (RNs) for every 100,000 people. The Canadian average is 814.

A 2019 survey of nurses conducted by the Canadian Federation of Nurses Unions, with researchers from the University of Regina, revealed that 83 per cent of nurses felt that their institution’s core health-care staff was insufficient to meet patient needs.

Bernhard recalls the defining moment that made her realize she couldn’t continue working full-time anymore.

One of her close friends, a colleague, was assaulted at work.

While this alone wasn’t enough to force her hand — Bernhard says assaults and violent patients had been growing more common over the past two years — the lack of protection and mental health support offered to staff working in such environments meant this was the “straw that broke the camels back.”

Bernhard says nurses are routinely having to deal with aggressive patients, being assaulted, and being placed on wards where they have no training or experience, with little support.

The Ontario government‘s one per cent wage increase cap per year on public sector employees — also known as Bill 124 — rubbed further salt in the wound, Bernhard says.

As a full-time nurse, Bernhard made $31.26 per hour — which, at 40 hours per week, works out to about $65,000 per year.

In going part-time, Bernhard will work 24 hours per week and will supplement that income with a role as an instructor on a nursing program at a local college, making $25.64 an hour.

When asked whether the government would be making further investments into the nursing sector during the Omicron surge, an Ontario government spokesperson said they had already “acted swiftly” to introduce schemes such as pandemic pay.

They also said they “took swift action” to impose restrictions this week to “blunt transmission and prevent hospitals from becoming overwhelmed,” which included cancelling non-emergent and non-urgent surgeries.

In response to questions about Bill 124, the spokesperson said it was “inaccurate” to suggest that wages were capped at one per cent, because employees could still “receive salary increases for seniority, performance, or increased qualifications.”

“Our government is incredibly grateful for the contributions of Ontario’s health-care workers and the critical role they have played throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, providing patients with timely, safe and equitable access to high-quality care,” the spokesperson said.

Read more:

Burnt-out health-care workers fear Omicron surges in Canadian hospitals

But for Bernhard, gratitude is not enough. She says the provincial government must step in with pay raises and mental health resources to ensure more nurses don’t step back as she has.

“We are so done,” she said, noting that public shows of support peppered throughout the pandemic can’t overcome the weight of the situation.

“Don’t worry about banging the pots and pans and keep your pizza – and I don’t need the accolades. What I need is the government to show up.”

Nearly one in five job vacancies in Canada in the first quarter of 2021 was in health care and social assistance, according to Statistics Canada.

Weekly overtime also increased on average by 78 per cent from May 2019 to May 2020.

Another survey, in February 2021, reported that 70 per cent of health-care workers reported their mental health had worsened during the pandemic.

A whopping 96 per cent pointed to workplace demands as the cause of their worsening mental health.

Burn out crisis in hospitals looming

Todd Else, a nurse at a major trauma centre in Toronto also stepped back from his full-time position last year, after a period of prolonged stress — giving up a full-time position to take a casual contract. He has been nursing for 23 years.

“I’ve been doing this a long time. And I’ve seen things sort of get worse and worse,” he says.

“When you walk into the department, and you see all these patients lined in the hallways who should be upstairs in wards, not lying in a structure in the middle of a busy [emergency department], that makes your heart sink.”

Else lost his mother and father within six months of each other at the beginning of the pandemic. It was that emotional trauma, coupled with the lack of pay, respect and resources, that led him to take a step back about a year ago.

Todd Else, a nurse at a major trauma centre in Toronto, had to take a step back from full-time work due to stress.

“There was a lot of emotional hardship for me during that time. And added with the pressure of what the hospital was going through at the time, ramping up with all this COVID — there was a lot of fear, a lot of misinformation … the stress was incredible.”

Else said he was unable to see his mother just before she died because he was working.

He lives alone and recalls “very isolated moments” not being able to see extended family while being on the front lines of the pandemic.

Omicron FAQ: Everything you need to know about the COVID-19 variant

Those feelings worsened with a feeling of “dejection” and “powerlessness” at work.

“At my [hospital], there’s less and less of us that have been there for a long time,” he says.

“You can definitely sense there is a growing growing dissatisfaction in the workplace due to the pressures of not only COVID, but just the hospital overcapacity, in general, has burned a lot of people out.”

Else says the current wave of infections caused by the Omicron variant is generally requiring people to be hospitalized for less time, but hospitals are being clogged by people with mild symptoms or who have been exposed to COVID who are unable to get tested in the community.

This has been pushing staff and resources to breaking point, as well as allowing the variant to spread through patients in the emergency department.

“You’re seeing this breakdown of infection controls, because we just don’t have the space or the geography to separate people properly. It starts out in the waiting room.

“So you’re seeing patients that potentially have COVID that are not being isolated, because we just simply don’t have the room.”

Government solutions not enough so far

In November in Ontario, the government announced as part of its fall economic statement that it’s investing $342 million to add and upgrade the skills of more than 5,000 registered nurses and registered practical nurses and 8,000 personal support workers.

Another $57.6 million will go toward hiring 225 more nurse practitioners in long-term care, starting next year.

On Sept. 23, Quebec announced a $1-billion plan to fix the province’s nursing crisis — offering nurses a bonus of between $12,000 and $18,000 to stay in full-time jobs, encouraging part-timers to go full-time and attracting 4,300 nurses back into the profession.

Read more:

‘It doesn’t fix the problem’: Nurses pan Quebec’s bonus offer, say real issue is mandatory overtime

Other provinces across Canada, such as Manitoba and Saskatchewan, are ramping up calls for assistance to deal with critical nursing shortages.

Advocates for the sector fear a looming crisis lies ahead if investment is not funneled into the sector now.

“Nurses have been working extra shifts, they haven’t had vacations for two years running. They’re working extended hours, required overtime, weekends, all the time. And their physical and emotional resources are very, very limited,” Hurley says.

Hurley says health-care workers had been given little support to deal with rising stress and violence at work and health-care decisions had been made “on the fly.”

Hurley also hit out at Ford’s mention of “absenteeism” during a press conference this week, in which the premier said various sectors were being strained due to workers being sick or requiring mandatory isolation after a COVID-19 exposure or infection.

“These people are working so hard to try to keep the health-care system together. If they catch COVID at work, it’s because likely they weren’t given the kind of protective equipment that they need to work safely.

“That kind of terminology is an example of the kind of carelessness which with which we treat these [people] who … deserve so much more for the contribution that they’ve been making.”

An Ontario government spokesperson did not respond to questions about Ford’s choice of words and whether the premier might offer a comment to those who felt offended by them.

Hurley said it has led nurses to feeling “undervalued” and “exploited” and will result in people leaving the profession “in droves.”

Read more:

Winnipeg ER doctors pen letter to province, health authorities over senior nurses quitting

“It makes them feel, you know, massively discouraged, and … a lot of them want to quit. A lot of them will quit after this pandemic — they’re holding on for the sake of the general public.”

A 2021 survey of nurses conducted by the Registered Nurses Association of Ontario reported that 4.5 per cent of nurses in Ontario planned to retire now or immediately after the pandemic.

At least 13 per cent of nurses aged 26-35 reported being “very likely to leave the profession” once the pandemic dies down.

U.S. contracts offer higher pay

Some health-care workers in Canada are already looking overseas for work.

Rhiannon Phillips, a nurse at an Ontario hospital, says she is considering taking a travel nursing contract in the U.S. to bolster her income.

She had been off work on maternity leave for a year but said the thought of returning to the stress of her workplace prompted her to begin looking elsewhere.

“Everyone is just so tired. And it’s one thing to be tired, but it’s another thing to be tired and sh-t on.”

Read more:

‘Burnt out and pushed beyond their limits’: nurses struggle to work and care for own families

She says if she took a contract in upstate New York, she could commute and make between $4,000 and $5,000 per week. She says there is “no incentive” to stay and work in Canada.

“Like many other people, we got into debt over the pandemic. And if I can work the same amount of hours but get a month’s pay in a weeks’ time — why not?”

Linda Silas, president of the Canadian Federation of Nurses Unions, says governments are offering a “patchwork of options” to retain workers, such as Quebec’s bonus scheme, that “is not working.”

She says she has watched over the past two years as younger nurses retire, many around the age of 55, labelling it a “huge loss to our workforce.”

“The government needs to wake up and reach out to these nurses and say, ‘we need you and we will modify workplaces for you to stay.’”

‘We are approaching that worst-case scenario’

Canadian Medical Association president Dr. Katharine Smart says the accelerated loss of experienced health-care workers has a “huge impact” on the sector, and many may have continued working if conditions were different.

Smart says “retention of staff is critical” as Canada approaches its “worst-case scenario” of a critical health-care worker shortage, compounded by illness and burnout.

Read more:

‘You just felt chronically tired’: COVID-19 pandemic burning out Canadian nurses

“What’s really scary is we are approaching that worst-case scenario where we’re seeing a significant percentage of health-care workers who are unable to work right now because of their own illness, or because of burnout and just not being able to carry on.

“And that’s a setup for disaster when you have that mismatch between the volume of patients needing care and the health-care workers on the ground able to deliver it.”

Smart says she hopes Ontario’s recently announced restrictions will “blunt the exponential growth” of the Omicron wave and its impact on hospitals.

“Is it too little too late? I think it’s hard to know. I mean, certainly where we’re at is no surprise. We all knew this in early December,” she says.

Read more:

Ontario pauses non-urgent surgeries ahead of expected Omicron impact

“We need to see governments get serious about naming this problem and committing to solutions. And we haven’t really heard that – we’ve heard words use like ‘absenteeism’ rather than really saying what it is.”

Bernhard agrees the government desperately needs to step in. Otherwise, more nurses may throw in the towel completely.

“We will continue to hold the line, regardless of how tired we are. Regardless of vaccination status, regardless of your conspiracy theories, regardless of anything else, we will continue to care for everyone to the best of our ability … but the government needs to start holding the line for us,” she says.

“We will continue to show up. But it’s getting so hard. It’s just getting so hard.”

View link »

© 2022 Global News, a division of Corus Entertainment Inc.

Discussion about this post