This composite image shows an infrared view of Saturn’s moon Titan from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft, acquired during the mission’s “T-114” flyby on November 13, 2015. New research on Titan’s seas using Cassini’s radar data shows varied surface compositions and slight roughness differences, highlighting complex environmental interactions on Saturn’s moon. Credit: NASA

Researchers from Cornell University have utilized bistatic radar data from

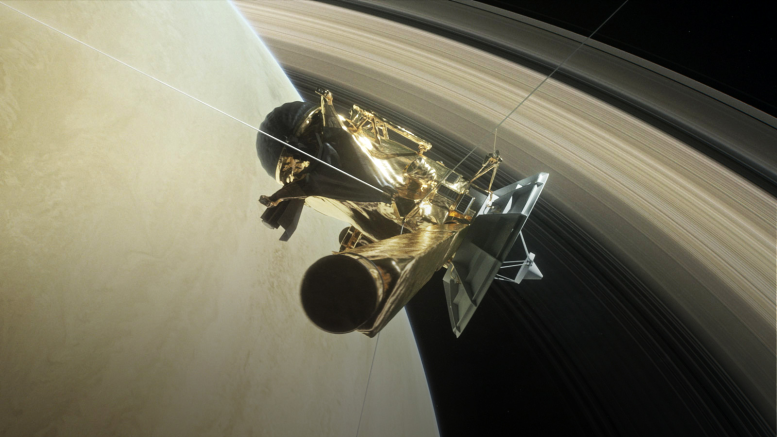

Artist’s depiction of NASA’s Cassini during its 2017 “grand finale,” in which the spacecraft dove between Saturn and its rings multiple times before purposefully crashing into the planet’s atmosphere. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Bistatic Radar Experiments

A bistatic radar experiment involves aiming a radio beam from the spacecraft at the target – in this case Titan – where it is reflected toward the receiving antenna on Earth. This surface reflection is polarized – meaning that it provides information collected from two independent perspectives, as opposed to the one provided by monostatic radar data, where the reflected signal returns to the spacecraft.

“The main difference,” Poggiali said, “is that the bistatic information is a more complete dataset and is sensitive to both the composition of the reflecting surface and to its roughness.”

Findings From Titan’s Polar Seas

The current work used four bistatic radar observations, collected by Cassini during four flybys in 2014 – on May 17, June 18, October 24, and in 2016 – on November 14. For each, surface reflections were observed as the spacecraft neared its closest approach to Titan (ingress), and again as it moved away (egress). The team analyzed data from the egress observations of Titan’s three large polar seas: Kraken Mare, Ligeia Mare, and Punga Mare.

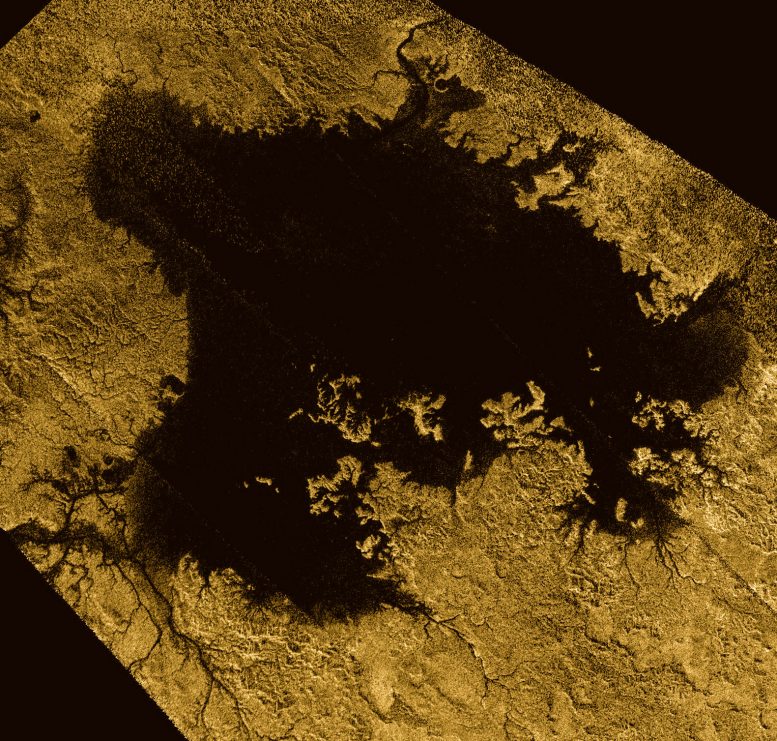

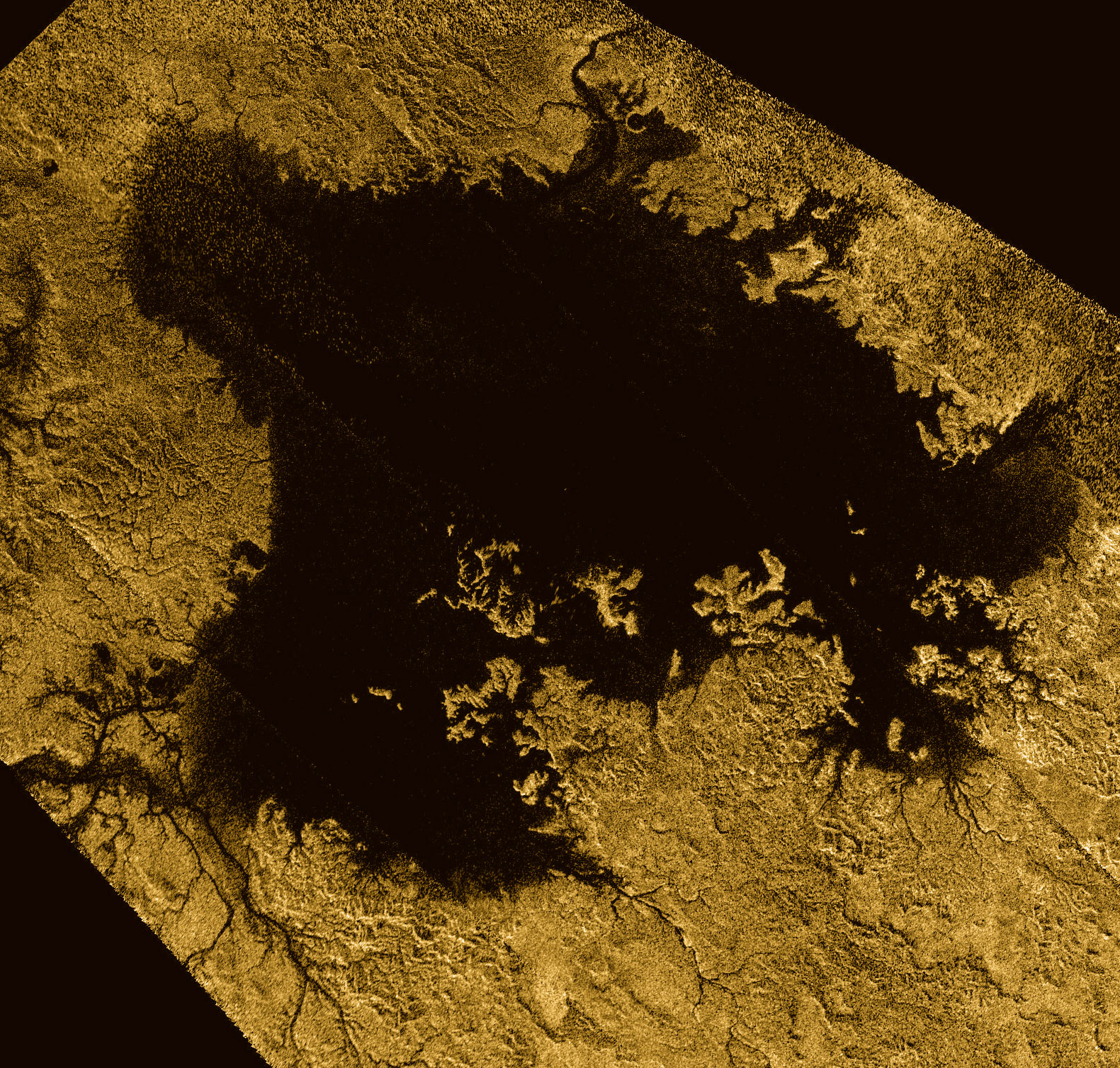

Ligeia Mare, shown in here in data obtained by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft, is the second largest known body of liquid on Saturn’s moon Titan. It is filled with liquid hydrocarbons, such as ethane and methane, and is one of the many seas and lakes that bejewel Titan’s north polar region. Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech/ASI/Cornell

Surface Composition and Dynamics

Their analysis found differences in the composition of the hydrocarbon seas’ surface layers, dependent on latitude and location (near rivers and estuaries, for example). Specifically, the southernmost portion of Kraken Mare shows the highest dielectric constant – a measure of a material’s ability to reflect a radio signal. For example, water on Earth is very reflective, with a dielectric constant of around 80; the ethane and methane seas of Titan measure around 1.7.

The researchers also determined that all three seas were mostly calm at the time of the flybys, with surface waves no larger than 3.3 millimeters. A slightly higher level of roughness – up to 5.2 mm – was detected near coastal areas, estuaries, and interbasin straits, possible indications of tidal currents.

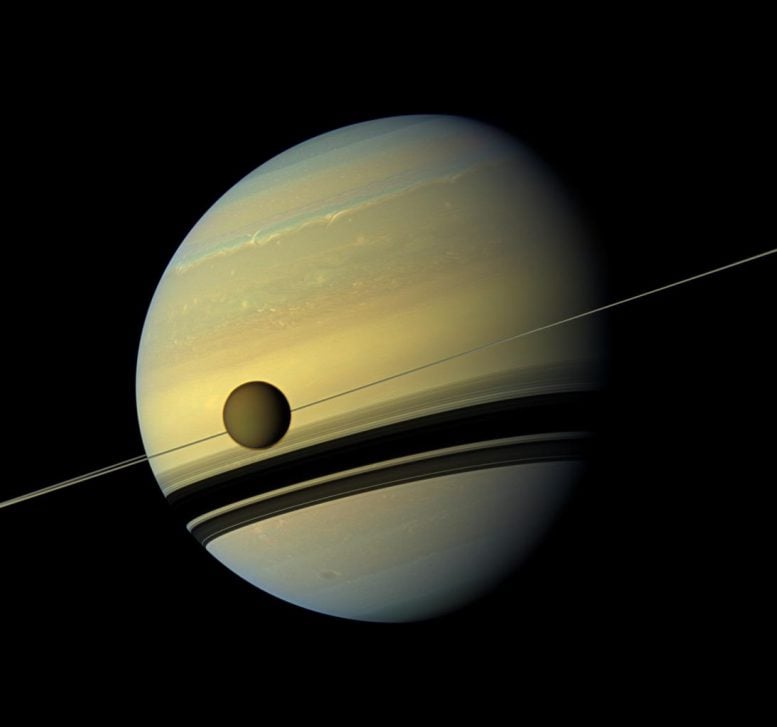

Larger than the planet Mercury, Huge moon Titan is seen here as it orbits Saturn. Below Titan are the shadows cast by Saturn’s rings. This natural color view was created by combining six images captured by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft on May 6, 2012. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

Implications and Future Research

“We also have indications that the rivers feeding the seas are pure methane,” Poggiali said, “until they flow into the open liquid seas, which are more ethane-rich. It’s like on Earth, when fresh-water rivers flow into and mix with the salty water of the oceans.”

“This fits nicely with meteorological models for Titan,” said co-author and professor of astronomy Philip Nicholson, “which predict that the ‘rain’ that falls from its skies is likely to be almost pure methane, but with trace amounts of ethane and other hydrocarbons.”

Poggiali said more work is already underway on the data Cassini generated during its 13-year examination of Titan. “There is a mine of data that still waits to be fully analyzed in ways that should yield more discoveries,” he said. “This is only the first step.”

Reference: “Surface properties of the seas of Titan as revealed by Cassini mission bistatic radar experiments” by Valerio Poggiali, Giancorrado Brighi, Alexander G. Hayes, Phil D. Nicholson, Shannon MacKenzie, Daniel E. Lalich, Léa E. Bonnefoy, Kamal Oudrhiri, Ralph D. Lorenz, Jason M. Soderblom, Paolo Tortora and Marco Zannoni, 16 July 2024, Nature Communications.

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-49837-2

Other contributors to this work are from the Università di Bologna; the Observatoire de Paris;

Discussion about this post