The Diplomat author Mercy Kuo regularly engages subject-matter experts, policy practitioners, and strategic thinkers across the globe for their diverse insights into U.S. Asia policy. This conversation with Dr. April Herlevi – senior research scientist in the Indo-Pacific Security Affairs Program at the Center for Naval Analyses – is the 375th in “The Trans-Pacific View Insight Series.”

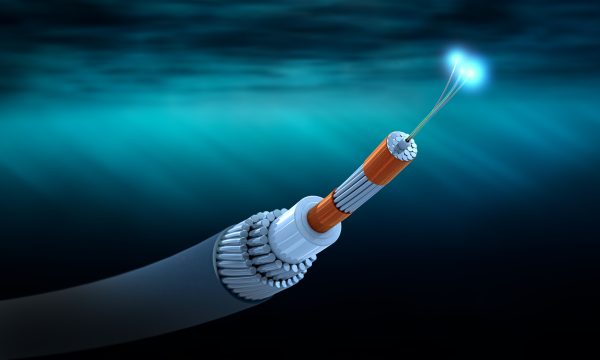

Explain U.S. security concerns over China’s involvement in laying fiber optic cables underwater connecting Asia to the United States.

First, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has passed a series of laws that impose rules on digital networks, which are of growing concern to foreign companies and individuals. The most prominent examples are the Cybersecurity Law, Data Security Law, Counter-Espionage Law, National Intelligence Law, and Cryptography Law. These laws come into play if cable lines have landing points in China, allowing the PRC government access to data, encryption keys, and other proprietary information.

Second, there are concerns about intelligence services gaining access to data transmitted through those cables. In a statement about the Pacific Light Cable Network, the U.S. Department of Justice noted concerns about PRC intelligence and “the PRC government’s sustained efforts to acquire the sensitive personal data of millions of U.S. persons.”

Third, there are privacy concerns. Views on privacy protection are diverging in Asia, Europe, and America. The European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation helps individuals control their personal data from both governments and corporations. U.S. laws protect individuals from government access, but private corporations have extensive access. China’s laws provide some protections from corporations, but also provide for government access to personal data. These vastly different approaches make it more difficult to protect privacy as data flows between continents.

Examine the competitive commercial stakes between Chinese (China Mobile, China Unicom, China Telecom, and Huawei/HMN Tech) and U.S. (Amazon, Google, Meta) industry players in securing subsea internet infrastructure.

The commercial competition is complex and moving quickly. According to the Financial Times, France, Japan, and the U.S. continue to build infrastructure and supply equipment for subsea cables. PRC firms control a smaller share of the current subsea internet infrastructure. Of the undersea cable projects with PRC involvement, Huawei was involved in about 45 percent of projects, based on data from the Australian Strategic Policy Institute’s Mapping China’s Tech Giants database. The other 55 percent of PRC cable projects were split among China Unicom, China Telecom, and China Mobile.

Mergers, acquisitions, and subsidiaries complicate the picture. For example, in 2020, Hengtong Group purchased Huawei Marine Networks, rebranding it as HMN Technologies. Hengtong Group is China’s largest cable manufacturing firm and owns over 70 different subsidiaries. In 2021, the U.S. Department of Commerce added the firm to the U.S. Entity List for supporting “military modernization for the People’s Liberation Army.” This prohibits Hengtong Group from receiving at least some items subject to Export Administration Regulations without a license.

As for the U.S. industry players, I leave that to experts on the U.S. tech sector.

Analyze the geopolitical risks of competing national interests in this domain.

The geopolitical risks differ between large economies, such as the China and the United States, and smaller economies with less access to the internet’s infrastructure. Despite impressive strides in satellite communications, the vast majority of internet traffic still flows through undersea cables that are vital to a country’s economic development, employment prospects, and education and health systems. Internet access dictates how a country can engage globally.

For countries that do not have the capacity to build their own networks, there are concerns about bandwidth allocation. For example, who has the authority to control or restrict the bandwidth within specific cables? Who conducts the repair and maintenance of the cable in the event of a natural disaster or other disruption?

In 2006, earthquakes off the coast of Taiwan caused internet outages in Taiwan, South Korea, and Southeast Asia. The repairs took nearly 50 days. In 2021, a volcanic eruption and subsequent earthquakes severed undersea cables connecting Tonga. The country was without high-speed internet for over three weeks, relying almost entirely on mobile phone networks during a major natural disaster. Access to high-speed internet has increasingly become a necessary public good for all. But the firms that build, control, and repair subsea network cables are private, so the risk of increasing disparities in access remains.

What is the potential impact of these risks on the health of the global internet and digital governance?

The risks differ for governments, companies, and individuals. For governments, the risks center on who controls the rules for digital sovereignty, data access, and the standards for how information is shared. In May, the White House released its U.S. Government National Standards Strategy for Critical and Emerging Technology, calling for the U.S. public and private sector to renew its commitment to setting technology standards.

For companies, profit is the main risk. Both U.S. and Chinese companies have invested in undersea cables to increase bandwidth capacity and expand their markets. For individuals, many digital governance issues exist including access, reliability, transparency, privacy, and the role of artificial intelligence. Questions remain about who owns your data.

Assess the U.S. government’s response to underwater internet infrastructure competition for market share and geopolitical influence.

I think U.S. government initiatives to safeguard internet infrastructure have been successful. France, Japan, and the U.S. continue to provide much of the equipment for subsea cables and the United States and its partners are providing infrastructure to improve connectivity, such as the East Micronesia Cable in the North Pacific. But the more important competition is taking place between content providers. Companies in both the U.S. and China are investing in undersea cables because of their own bandwidth needs and to increase market share, and this raises privacy questions for individuals.

Media scholar Aynne Kokas has described the “U.S. tech sector as one defined by exploitative practices.” In the Chinese market, national champions must work within the PRC government’s model of cyber sovereignty, which includes controls on internet access and content. Different data ecosystems are emerging. Yet, those differences have not stopped the flow of data globally – at least not yet – so more work will need to be done to ensure internet infrastructure is trusted and secure.

Discussion about this post