When bureaucrats get big promotions, they tend to receive congratulations from their friends, but after Christopher Miller landed the biggest job of his life, his wife and some of his colleagues were horrified.

It was November 9, 2020, the day President Donald Trump fired his secretary of defense, Mark Esper. It was widely assumed that Trump would install an acolyte who would do whatever was needed to help the defeated president stay in power. Esper, just days before, had confided to a journalist, “Who’s going to come in behind me? It’s going to be a real yes man. And then God help us.”

Trump appointed Miller, an unknown whose rise was so far-fetched that the secretary of the Army, Ryan McCarthy, had to Google his new boss to figure out who he was. Wikipedia was useless because at the time, Miller didn’t merit an entry.

After retiring from the Army as a Special Forces colonel in 2014, Miller moved from one mid-level job to another in Washington, D.C., a nobody in a city of somebodies. Things began to pick up after Trump’s election, and by August 2020, he was promoted to director of the National Counterterrorism Center. Just three months later, he was summoned to the Oval Office and put in charge of the world’s most powerful military.

“I’m at work on a Monday morning, and the phone rings, and they’re like, ‘Get your ass down here,’” Miller said in an interview, referring to the moment he was called to the White House. “I was like, ‘Oh, shit.’”

Miller knew his name was circulating in the White House, but the announcement came abruptly and was not greeted with warmth by his life partner. “Yeah, my wife is like, ‘The only thing we have is our name and you’re ruining it,’” Miller recalled. “She’s like, ‘You’re an idiot. I think this is the stupidest thing that’s ever happened.’ And I’m like, ‘Yes dear, I know that.’”

Photo: Department of Defense

As improbable Washington stories go, Miller’s blink-and-it’s-over journey from Beltway nothingness to what his detractors regard as a semi-witting participant in a plot to overthrow the constitutional order — well, it’s quite something. Miller was in charge of the Pentagon on January 6, 2021, and is accused of delaying the deployment of National Guard troops so the mob that beat its way into the Capitol might succeed in creating more than a pause in the Senate’s count of Electoral College votes. At a combative oversight hearing a few months later, Democratic members of Congress derided Miller as “AWOL,” “disgusting,” and “ridiculous,” to which he responded, “Thank you for your thoughts.”

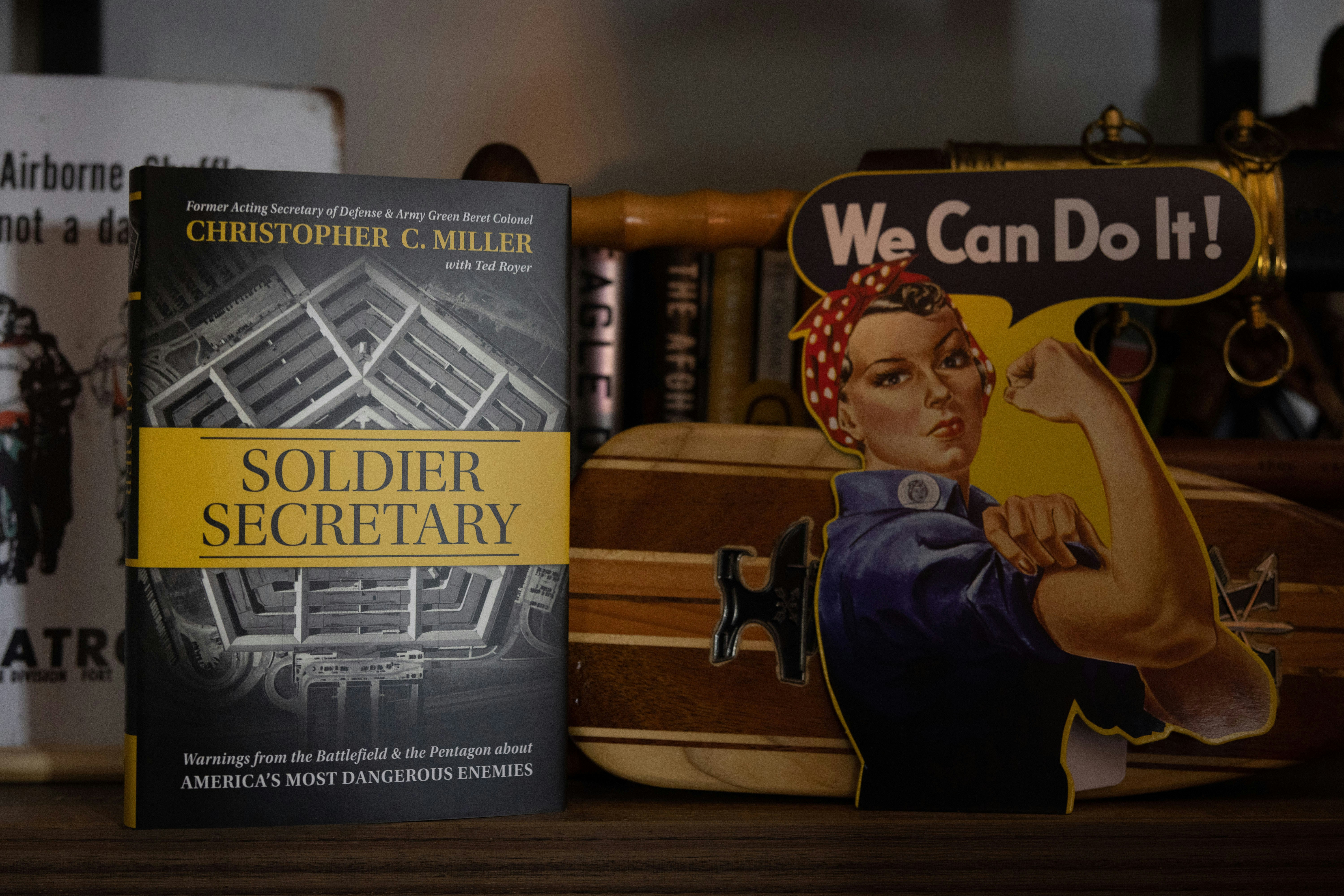

As is customary, Miller has written a memoir of his extremely brief time in power, “Soldier Secretary,” published last month by Center Street, whose other authors include Newt Gingrich and Betsy DeVos. It’s a typical Washington book in many ways — revealing at times, suspect at others. For instance, Miller describes House Speaker Nancy Pelosi as suffering a “total nuclear meltdown” during a phone call with him on January 6, but there is no evidence for that characterization. His book sticks closely to the Beltway norm of having a principal character who displays calmness and reason while others go nuts; the principal character is the author.

His rhetoric is a profane blend of MAGA and Noam Chomsky.

But just as Miller’s journey to the top is atypical, so too is his obscenity-flecked memoir, because the retired soldier emerges as a scorched-earth critic of the institution he served for more than three decades and presided over for 73 days. He wants to fire most of the generals at the Pentagon, slash defense spending by half, shut down the military academies, break up the military-industrial complex, and he describes the invasion of Iraq as an unjust war based on lies. His rhetoric is a profane blend of MAGA and Noam Chomsky.

“Today, there are virtually no brakes on the American war machine,” Miller writes. “Military leaders are always predisposed to see war as a solution, because when you’re a hammer, all the world’s a nail. The establishments of both major political parties are overwhelmingly dominated by interventionists and internationalists who believe that America can and should police the world. Even the press — once so skeptical of war during the Vietnam era — is today little more than a brood of bloodthirsty vampires cheering on American missile strikes and urging greater involvement in conflicts America has no business fighting.”

I was as surprised as everyone else when I heard the news about Miller’s appointment, but it’s not because I had to Google him. I knew who he was. We first met in Afghanistan in 2001, when he was a leader of the Special Forces unit that chased the Taliban out of their final stronghold, and I was reporting on that for the New York Times Magazine. I got to know him and wrote an article in 2002 about his Afghan combat and his preparations for the Iraq invasion the following year. With the publication of his memoir, Miller is now making the media rounds, so we got together again.

After more than two decades of the forever wars, Miller is pissed off in the way a lot of former soldiers are pissed off — and, I have to say, in the way a lot of former war reporters are pissed off too. It’s hard to have been a participant in those calamities and not feel betrayed in some fashion, as pundits attempt to whitewash the disaster and promotions are announced for officials who masterminded it. Miller’s evolution from Special Forces operator to Trump Cabinet member is a forever wars parable that helps us understand the moral injury festering in our political corpus.

Photo: Alyssa Schukar for The Intercept

A Historic Error

Miller’s 9/11 journey got into literal high gear when he roared into Kandahar in a Toyota pickup with blown-out windows. It was December 2001, he was a 36-year-old major in the 3rd Battalion of the 5th Special Forces Group, and this was his first combat deployment.

I spotted Miller at the entrance to a compound on the outskirts of the city. Until a few days earlier, it had been the residence of Mullah Mohammed Omar, the spiritual leader of the Taliban who, after Osama bin Laden, was the most hunted man in the country. The scene was surreal because the compound was now the temporary home of Hamid Karzai, the soon-to-be leader of Afghanistan, whose security was guaranteed by Miller’s soldiers. These just-arrived Americans were dressed half in camouflage, half in fleece jackets, and they sported the types of accessories that ordinary GIs were prohibited from having, such as beards and long hair. Mixed among them were Afghan fighters with AK-47s who had fought with the Taliban not long ago but switched loyalties, which is an accepted practice in Afghanistan when your team is losing.

I struck up a conversation with Miller, a tall officer with bushy red hair and a wicked-looking assault weapon slung over his shoulder. Most of his soldiers were silent and grim — they weren’t happy about the journalists who had shown up — but Miller, who recognized my name because he had read my memoir on the Bosnian war, was friendly and answered a few questions. I asked if he had been to Bosnia, and he gave me a vague special operator laugh and said, “I’ve been everywhere, man.” As it turned out, he’d worked undercover in Bosnia in the late 1990s alongside CIA operatives tracking Serb war criminals.

I stayed in Kandahar for a while longer, as did Miller. We were both spending time around the city’s U.S.-installed warlord, Gul Agha Shirzai, whom Miller describes in his book as “a self-serving piece of shit,” which is totally accurate. After we both returned to America, I got Miller to invite me to spend a few days at his battalion’s headquarters at Fort Campbell, Kentucky. We talked for hours about what happened in Afghanistan, about the soldiers he lost, about the Al Qaeda fighters he helped kill, and about the next war on the horizon (this was a year before the illegal invasion of Iraq). Miller was as friendly and transparent as I could hope for from a Special Forces officer. His favorite word was “knucklehead,” which he sometimes used to describe himself.

Miller didn’t know it at the time, but he was at the cusp of a profound disenchantment with the country’s military and political leaders, a disillusionment he shared with a lot of soldiers, thanks to the deceptions and errors embedded in the wars they fought. Miller is exceptional only in his Cabinet-level end point. While it’s important to remember that the vast bulk of these veterans are law-abiding, a small but influential group have been radicalized to violence rather than government service.

Veterans are one of the key subjects in historian Kathleen Belew’s lauded book about right-wing extremism, titled “Bring the War Home.” American history teaches us a consistent lesson: There will almost always be blowback at home from wars fought elsewhere. Of 968 people indicted after the storming of the Capitol, 131 have military backgrounds, according to the Program on Extremism at George Washington University. Due to the respect military service generates among civilians in right-wing movements, veterans composed a disproportionately large number of the ringleaders on January 6, including Oath Keepers founder Stewart Rhodes, who was convicted of seditious conspiracy last year.

Soon after we met in 2001, Miller noticed omens of dysfunction in the American war machine. It began, he wrote in his book, with a visit to the airport that U.S. Marines seized outside Kandahar a few days after the Special Forces sped into town in their four-wheel-drive vehicles. Miller and one of his sergeants had to pick up supplies at the airport, and they saw Marines putting up a big tent. The sergeant told Miller, “Sir, it’s time for us to get the fuck out of here.” Miller asked why, and the sergeant replied, “They’re building the PX. It’s time for the Green Berets to leave.”

“We should have kept it to about 500 people, just let that be the special operations theater.”

He meant the military was settling in for the long haul. Sprawling bases would be constructed with Burger King and Pizza Hut outlets, staffed by workers flown in from Nepal, Kenya, and other countries. There would be more than 100,000 U.S. troops in Afghanistan at the peak of President Barack Obama’s surge, and hundreds of billions of dollars spent in the country, yielding decades of full employment for generals and executives in the weapons industry. Miller had a front-row seat at this carnival. “We should have kept it to about 500 people, just let that be the special operations theater,” he told me. In other words, quickly arrange a power-sharing deal between Karzai and the Taliban rather than try to eliminate the Taliban and leave a small number of special operators to find and kill Osama bin Laden and the remnants of Al Qaeda.

I don’t think Miller sensed all this when he saw that tent going up; nobody knew what was going to happen that early in the game. And remember, you can’t trust Beltway memoirs; they’re a racket of myth construction. But locating the exact moment of Miller’s awareness is less important than the fact he eventually recognized, as most of us did, a historic error that he blamed on his leadership. “As soon as we went conventional, that war was lost,” Miller said. “That’s what I’ll take to my grave. As soon as we brought in the Army generals and all their big ideas — war was over at that point.”

Christopher Miller in old photos from his time in Afghanistan, left, and Iraq, right.Photos: Alyssa Schukar for The Intercept

The Betrayal

Like many veterans, Miller participated in not just the Afghanistan disaster, but also the one in Iraq. There he had an even stronger sense of betrayal.

As the invasion neared, Miller was responsible for operational planning for his Special Forces battalion, and he put together a blueprint for seizing an airfield southwest of Baghdad as an advance position for the capture of Iraq’s capital. He thought the buildup was a bluff to coerce Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein into giving up the weapons of mass destruction that the Bush administration insisted he possessed (though he did not). In Miller’s telling, it wasn’t until he was geared up in an MH-53 helicopter at night, heading deep into Iraq, that he knew it was on. The future acting defense secretary turned to a soldier next to him and said, “We’re really doing this. I can’t believe we’re fucking doing this.” According to Miller, the soldier replied, “Me neither.”

Miller and I were sitting in a café at the public library in Westport, Connecticut — he lives in northern Virginia and was visiting this wealthy suburb for a fundraiser for a play about the Special Forces. He was dressed in khaki pants and a casual shirt, and his shag of red hair from 20 years ago was gone; it had thinned out to a distinguished-looking silver. He is 57 years old now and looks no different from any other close-to-senior citizen killing time at a library (same goes for me, I should confess). He sipped his coffee and continued, “Invading a sovereign country is a big deal, you know. We typically don’t do that except in extenuating circumstances. I thought it was all coercive diplomacy. Then when it goes down, you’re like, ‘Damn.’” As he writes in his book, “I had been an active participant in an unjust war. We invaded a sovereign nation, killed and maimed a lot of Iraqis and lost some of the greatest American patriots to ever live — all for a god-damned lie.”

“You can mess up a piece of paperwork and get run out of the Army. But you can lose a damn war and nobody is held accountable.”

If your nation calls on you to send your comrades to their deaths in battle, you expect it will be for a good reason; soldiers have a lot more at stake than Beltway hawks for whom a bad day consists of getting bumped from their hit on CNN or Fox. That’s why Miller describes himself as “white-hot” angry toward the leaders who lied or dissembled and suffered no consequences; many have profited in retirement, thanks to amply compensated speaking gigs and board seats. “You can mess up a piece of paperwork and get run out of the Army,” Miller told me. “But you can lose a damn war and nobody is held accountable.”

If that line came from a pundit, it would be a platitude. But Miller described to me the case of a soldier he knew well who was forced out of the military for not having the paperwork for a machine gun he left in Afghanistan for troops replacing his unit. The soldier was trying to help other soldiers who didn’t have all the weapons they needed. It didn’t matter; he was gone, and Miller couldn’t stop it.

Miller trembled a bit as he narrated this story. Maybe he was on the verge of tears; I couldn’t be sure. There’s a saying in journalism that if your mother says she loves you, check it out. Never trust a source, especially one selling a book and an image of himself. As these things always are, our conversation was a bit of a performance by each of us, both trying to get out of the other as much as we could. Miller’s intentions were hard to pin down, but his anger was not. I had seen some of what he had seen.

In 2014, after three decades in the Army and more than a dozen deployments to Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Kuwait, Bosnia, and elsewhere, Miller retired. He had a lot of baggage to deal with. As he writes, “For years I had been cramming unpleasant memories into a box and storing them on a shelf deep in the recesses of my psyche, knowing that someday I’d have to unpack each one.”

He set a goal: Complete a marathon in less than three hours. His long practice runs of 15-25 miles were, as he put it, therapy sessions to work through the wreckage of the wars he fought and “a simmering sense of betrayal that every veteran today must feel — the recognition that so many sacrifices were ultimately made in the service of a lie, as in Iraq, or to further a delusion.” After running that marathon, he entered a 50-mile race on the Appalachian Trail and finished in less than eight hours, ranking second in his age group.

There were no epiphanies at the end. Physical exhaustion would not eliminate his bitterness about Iraq and Afghanistan. “It still makes my blood boil,” he writes, “and it probably will until the day I die.”

Photo: Staff Sgt. Jack Sanders/DoD

More Juice

While Miller describes himself as falling “ass-backwards” into the job of acting secretary of defense, you don’t rise to the top by mistake in Washington, and people who run ultramarathons don’t tend to be lily pads just floating along. Miller has a gosh-darn way of talking, and even his detractors describe him as affable, but he’s a special operator, and you shouldn’t forget that. After retiring from the military, he made a series of canny moves to join the National Security Council, at the White House and pair up with a key figure in Trump’s orbit, Kash Patel.

Patel became Washington famous in the first years of the Trump era because, as an aide to Rep. Devin Nunes, he played a behind-the-scenes role in the GOP effort to undermine special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation of Russian interference in the 2016 election. In early 2019, Patel was rewarded with a job on the NSC, reportedly on direct orders from Trump. Miller had joined the NSC the previous year as senior director for counterterrorism and transnational threats, and Patel became his deputy. Miller claims that initially, he was wary.

“I got online and Wikipedia’d him, and I’m like, ‘Oh my God, this is the crazy guy,” he told me with a laugh.

What happened next could be a how-to guide for Beltway strivers.

“I just had convening authority,” Miller recalled of his time at the NSC. “I’m like, ‘That’s bullshit.’ So I went to the Pentagon and took a job as a political appointee because I needed to have money and people.”

It was early 2020 when he became deputy assistant secretary of defense for special operations and combating terrorism. This gave him greater influence over the hunt for ISIS and Al Qaeda terrorists, which had been his obsession at the NSC. Yet it wasn’t enough. As Miller describes it, “Now I had people, now I had money, but still not being very successful. … I still need more juice.”

Kash Patel, former chief of staff to then-Acting Secretary of Defense Christopher Miller, departs from a deposition meeting on Capitol Hill with the House select committee investigating the January 6 attack, on Dec. 9, 2021, in Washington, D.C.

Photo: Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images)

One of his friends in the administration made a suggestion: Why don’t you shoot for a Senate-confirmed position?

“I was like, ‘That gives me more wasta, right?’” Miller said, using an Arabic word for clout. “And I’m like, ‘Shit yeah.’”

Trump nominated him to head the National Counterterrorism Center, and on August 6, the Senate confirmed him in a unanimous voice vote.

“So now I’ve got more fucking throw weight,” Miller continued. “Patel’s working in the National Security Council with the president. We’re starting to grind down the resistors.” The resistance, he said, was against a heightened effort he and Patel advocated to finish off the remaining leaders of Al Qaeda and rescue a handful of remaining American hostages.

Miller was invited for a talk with Johnny McEntee, the head of the White House Presidential Personnel Office. In the twilight of the Trump era, McEntee was one of the president’s most loyal confidantes; though just 29 years old at the time, he was described, in a magazine article, as the “deputy president.” Miller knew through the grapevine that he might be in line for Esper’s job because the administration had just a few Senate-confirmed officials with national security credentials. McEntee was sizing him up.

“I’m like, ‘Oh shit,’ because I didn’t want the job,” Miller told me.

This was part of Miller’s “ass-backwards” shtick. Why grind as hard as he did to stop short of the biggest prize of all? I pushed back, and he acknowledged that while the job might “suck really, really badly,” it could be worthwhile even if Trump lost the election. “I had a work list,” Miller said. “I thought, ‘I can get a lot of shit done.’” His main tasks, he told me, included stabilizing the Pentagon after Esper’s ouster; withdrawing the remaining U.S. forces from Iraq, Afghanistan, and Somalia; and elevating special operations forces in the Department of Defense’s hierarchy.

Just before the election, he heard the shuffle was imminent.

“The word comes down: They’re getting rid of Esper, win or lose,” Miller said. “It’s payback time.”

On Monday morning, six days after Trump lost the election, Miller’s phone rang. Come to the White House, now.

Photo: Dustin Satloff/Getty Images

Murderer’s Row

Miller suffered a literal misstep his first day on the job: Walking into the Pentagon, he tripped and nearly fell on the steps in front of the mammoth building. That prompted laughs online, but the bigger issue was the entourage that surrounded him as he took charge of the nearly 3 million soldiers and civilians in the Department of Defense.

He was accompanied by a murderer’s row of Trump loyalists. Patel was his chief of staff. Ezra Cohen, a controversial analyst, got a top intelligence post. Douglas Macgregor, a Fox News pundit, became a special assistant. Anthony Tata, a retired general who called Obama a “terrorist leader,” was appointed policy chief. Gen. Mark Milley, chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, was reportedly so alarmed that he told Patel and Cohen, “Life looks really shitty from behind bars. … And if you guys do anything that’s illegal, I don’t mind having you in prison.”

Miller, when I asked about his advisers, waved off the concerns and said, “Complete misappreciation of those people.”

Cutting the U.S. footprint overseas was one of his top priorities, the residue of his long journey through the forever wars. It was a big part of his support for Trump, who was far more critical of those wars than most politicians. In the 2016 primaries, Trump distanced himself from other Republicans by accusing the George W. Bush administration of manufacturing evidence to justify the Iraq invasion. “They lied,” Trump declared at a debate in South Carolina, drawing boos from the Republican audience. “They said there were weapons of mass destruction. There were none, and they knew there were none.” This was an occasion on which Trump’s political interests — trying to embarrass front-runner Jeb Bush, the brother of the former president — aligned with something that was actually true.

Once he got to the White House, though, Trump didn’t make a lot of changes. Since 9/11, the generals who oversaw America’s wars had resisted when civilian leaders said it was time to scale back. And Trump actually quickened the tempo of some military operations by offering greater support to the disastrous Saudi-led war in Yemen and taking an especially hawkish position on Iran. But he was stymied on Iraq and Afghanistan, not just by active-duty generals at the Pentagon, but also by the retired ones he appointed to such key posts as national security adviser, chief of staff, and secretary of defense. They were all gone by the final act of his presidency.

By the time Miller left the Pentagon when President Joe Biden was sworn in, U.S. forces in Afghanistan and Iraq had been cut to 2,500 troops in each country (from about 4,000 in Afghanistan and 3,000 in Iraq). The approximately 700 soldiers based in Somalia were withdrawn. But that would not be Miller’s most memorable legacy.

The Phantom Meltdown

It was mid-afternoon on January 6, 2021. A pro-Trump mob had bashed its way through police barricades and invaded the Capitol. Ashli Babbitt had been shot dead. The rioters who occupied the Senate chamber included a half-naked shaman wearing a horned helmet and carrying a spear. Where was the National Guard?

Miller was the one to know, which is why he was on the phone with Nancy Pelosi at 3:44 p.m.

“I was sitting at my desk in the Pentagon holding a phone six inches away from my ear, trying my best to make sense of the incoherent shrieking blasting out of the receiver,” he writes on the first page of his book. “House Speaker Nancy Pelosi was on the line, and she was in a state of total nuclear meltdown. To be fair, the other members of congressional leadership on the call weren’t exactly composed either. Every time Pelosi paused to catch her breath, Senator Mitch McConnell, Senator Chuck Schumer, and Congressman Steny Hoyer took turns hyperventilating into the phone.”

That passage in Miller’s five-page introduction got a bit of attention on social media when it was first excerpted in January, and not all of it was positive. Wonkette described Miller’s account as “verifiably false” and pointed its readers to a video released by the January 6 committee showing Pelosi and other congressional leaders speaking in urgent but calm voices with Miller. They asked him to send troops immediately and demanded to know why it was taking so long. Pelosi is intense but not melting down; McConnell, Schumer, and Hoyer are not hyperventilating.

When I met Miller in Westport, I asked if he was aware of this discrepancy. He became slightly agitated.

“The one they show is a different call,” he replied. “The one used [by] the January 6 committee is a later phone call where they’re much calmer. The first call was frantic. Like literally losing their shit. … So that’s bullshit, dude.”

He told me to look into it.

The January 6 committee released partial footage of two calls that show Pelosi speaking with Miller. The first call, according to the time stamp on the committee’s video, occurred at 3 p.m. The sequence begins with Pelosi sitting near Schumer, who is holding a cellphone and saying, “I’m going to call up the effing secretary of DOD.” The next shot shows Schumer, Pelosi, and Hoyer huddled around the phone talking with Miller in measured voices; McConnell is not shown in this clip. The second call for which the committee released some footage is the one Wonkette pointed to. The participants in this second call are the ones mentioned by Miller in his book: McConnell is in this footage, along with Pelosi, Schumer, and Hoyer. There are no meltdowns. The committee’s time stamp for this call is 3:46 p.m., which is a nearly exact match for the time Miller provides in his book: 3:44 p.m.

What this means is that the phone call Miller described in his book almost certainly is the one Wonkette pointed to and did not occur the way Miller describes, unless there is an incriminating portion of the video we have not seen, which is what Miller claims. Yet that seems unlikely because there is no mention, in the multitude of testimonies and articles about that day, of Pelosi melting down at any moment. And that makes another passage in Miller’s introduction problematic too.

“I had never seen anyone — not even the greenest, pimple-faced 19-year-old Army private — panic like our nation’s elder statesmen did on January 6 and in the months that followed,” Miller wrote. “For the American people, and for our enemies watching overseas, the events of that day undeniably laid bare the true character of our ruling class. Here were the most powerful men and women in the world — the leaders of the legislative branch of the mightiest nation in history — cowering like frightened children for all the world to see.”

Except they weren’t cowering. They had been evacuated by security guards to Fort McNair because a mob of thousands had broken into the Capitol screaming “Where’s Nancy?” and “Hang Pence!” Miller makes no mention in his book of the speech Trump delivered on January 6 that encouraged his followers to march on the Capitol. There is no mention of the fact that while Pelosi and others, including Vice President Mike Pence, urged Miller to send troops, Trump did not; the commander in chief did not speak with his defense secretary that day. Although Miller has elsewhere gently described Trump’s speech as not helping matters, his book mocks the targets of the crime rather than criticizing the person who inspired and abetted it.

“Prior to that very moment, the Speaker and her Democrat colleagues had spent months decrying the use of National Guard troops to quell left-wing riots following the death of George Floyd that caused countless deaths and billions of dollars in property damage nationwide,” he writes. “But as soon as it was her ass on the line, Pelosi had been miraculously born again as a passionate, if less than altruistic, champion of law and order.”

Miller’s anger is real, but his target is poorly chosen, which is the story of America after 9/11.

This is unbalanced because the violence in the summer of 2020 — on the margins of nationwide protests that were overwhelmingly peaceful — did not endanger the transfer of power from a defeated president to his duly elected successor. The buildings that were attacked were not the seat of national government. And there weren’t “countless deaths” — there were about 25, including two men killed by far-right vigilante Kyle Rittenhouse in Kenosha, Wisconsin. The rhetoric in Miller’s book has the aroma of reheated spots from Fox News.

The contours of his political anger comes into clearer focus after reading a passage from his chapter on Iraq. He recalled his pride in the swift capture of Baghdad, but as he flew home in a C-17 aircraft, he couldn’t fully enjoy the triumph, couldn’t really unwind. “The further we got from the war zone, the more my stress turned into burning white-hot anger,” he wrote. He returned to an empty house in North Carolina — his family was in Massachusetts for the July 4 holiday — so he worked out, drank some beer, and read a lot. It didn’t help much. There was, as he put it, “a rage building inside me” that was directed at two groups. The first was the group he regards as the instigators, “the neoconservatives who bullied us into an unjust and unwinnable war.” The second was Congress “for abrogating its constitutional duties regarding the declaring, funding, and overseeing of our nation’s wars.”

Miller’s homecoming was reenacted by a generation of bitter soldiers, aid workers, and journalists. His list of culprits is a good one, though I would add the names of President George W. Bush and Vice President Dick Cheney to the top, because they issued the orders that destroyed Iraq. Their omission from Miller’s list, combined with his rant against Pelosi, reveals how his outrage follows a strange path, focusing on a political party that, while energetically backing the wars, was not the one that started them. And Democrats did not foment the storming of the Capitol either.

Miller’s anger is real, but his target is poorly chosen, which is the story of America after 9/11.

Photo: Alex Wong/Getty Images

The Clusterfuck

Just as the Watergate scandal had its 18-minute gap, there’s a now-infamous gap of more than four hours between the storming of the Capitol and the arrival of National Guard troops around 5:30 p.m. Miller is at the center of the controversy because the singular status of the District of Columbia means the Pentagon controls its National Guard — and Miller was the Pentagon boss on January 6.

The January 6 committee, which deposed Miller and other military and police officials, said in its 814-page final report that it “found no evidence that the Department of Defense intentionally delayed deployment of the National Guard.” The committee blamed the delay on “a likely miscommunication” between multiple layers of civilian and military officials. The abundant depositions reveal that the committee was being extremely kind when it chose the word “miscommunication.” Soldiers have a special word to describe what seems to have happened at the Pentagon: a clusterfuck.

At 1:49 p.m., as pro-Trump demonstrators beat their way past police lines, the head of the U.S. Capitol Police force called the commander of the D.C. National Guard, Gen. William Walker, and notified him there was a “dire emergency” and troops were needed immediately. Walker alerted the Pentagon, and a video conference convened at 2:22 p.m. among generals and civilian officials, though not Miller. Walker told the January 6 committee that generals at the Pentagon “started talking about they didn’t have the authority, wouldn’t be their best military advice or guidance to suggest to the Secretary that we have uniformed presence at the Capitol. … They were concerned about how it would look, the optics.”

The “optics” refers to the Pentagon being sharply criticized after National Guard soldiers helped suppress Black Lives Matters protests in the capital on June 1, 2020. Lafayette Square, just outside the White House, was violently cleared in a controversial operation that even involved military helicopters flying low at night to disperse protesters. At one point, Trump triumphantly emerged from the White House with a retinue that included Defense Secretary Esper and Milley; later, both men apologized for allowing themselves to be connected to the crackdown. After that debacle, the Pentagon was reluctant to involve troops in any crowd control in the capital, and local leaders made clear that they opposed it too; there was no appetite to amass troops that Trump might misuse.

Yet the storming of the Capitol, taking law enforcement by surprise, created an emergency that justified using the Guard. As Walker told the committee, “I just couldn’t believe nobody was saying, ‘Hey, go.’” Walker testified that he admonished the generals and officials on the 2:22 p.m. call: “Aren’t you watching the news? Can’t you see what’s going on? We need to get there.”

Army Secretary Ryan McCarthy — who two months earlier had to Google Miller’s name to figure out who he was — testified that he joined the 2:22 p.m. call and then ran a quarter mile through Pentagon hallways to Miller’s office, arriving there out of breath (“I’m a middle-aged man now,” he told the committee. “I was in a suit and leather shoes.”). At 3:04 p.m., Miller gave a verbal order for the mobilization of the D.C. Guard. It was an hour-and-a-quarter since the Capitol Police’s first plea for help, but it would take more than two additional hours for the troops to get there. This is the delay Miller has been particularly blamed for, though it does not appear to have been his fault alone.

Miller regarded his 3:04 p.m. order as final; Walker and his direct civilian commander, McCarthy, now had a green light to move troops to the Capitol, Miller testified. Some troops were already prepared to go there, according to the committee report. A ground officer, Col. Craig Hunter, was ready to move with a quick reaction force of 40 soldiers and about 95 others who were mostly at traffic control points in the area. Despite Miller’s 3:04 p.m. order, it would be hours before Hunter would be told to roll.

Photo: Samuel Corum/Getty Images

The committee’s report includes a 45-page appendix that’s a catalogue of recriminations among Walker, McCarthy, Miller, and others. Their depositions offer conflicting accounts of what was said in chaotic conversations that day, and they even disagree about whether certain conversations took place. They also express contrary views on who had the authority to issue orders, precisely what orders were needed, and what some orders even meant. The depositions were taken under oath, so despite their contradictions, they are the best record we have about what happened and far more reliable than most of the books and interviews that some of the principals have produced.

McCarthy prioritized the time-consuming task of drawing up an operational plan that doesn’t appear to have been necessary because Hunter’s troops were already equipped for riot control and knew what to do and where to go. McCarthy also spent a lot of time talking on the phone to politicians and journalists, as well as joining a press conference. As he told the committee, “So it went into the next 25 minutes of literally standing there, people handing me telephones, whether it was the media or it was Congress. And I had to explain to all of them, ‘No, we’re coming, we’re coming, we’re coming.’ So that chewed up a great deal of time.”

Meanwhile, Walker said he couldn’t reach McCarthy to find out whether he had permission to send his troops to the Capitol. Testifying on April 21, 2022, Walker said he was never called by McCarthy and was unable to contact him directly because the work number he had for McCarthy didn’t function: An automated message said, “This phone is out of service.” One of his officers happened to have McCarthy’s private cellphone number, but there was no answer on it. “The story we were told is that he is running through the Pentagon looking for the secretary of defense,” Walker testified. “That’s why he wasn’t answering his phone.” (McCarthy insisted in his testimony that they had talked.)

The delay wasn’t due to faulty telecommunications alone. McCarthy told the committee that he believed he needed another order from Miller, beyond the one issued at 3:04 p.m., before he could tell Walker to move. Miller issued an additional order at 4:32 p.m., but McCarthy failed to immediately inform Walker; the order didn’t reach the National Guard commander until 5:09 p.m., when a four-star general happened to notice Walker in a conference room and said, “Hey, we have a green light, you’re approved to go.” By the time Walker’s troops arrived at the Capitol, the fighting was over, and they were asked to watch over rioters already arrested by the bloodied police.

Toward the end of his testimony to the January 6 committee, Miller was asked why Walker had not scrambled his troops sooner. “Why didn’t he launch them?” Miller replied. “I’d love to know. That’s a question I was hoping you’d find out. … Beats me.”

Photo: Alyssa Schukar for The Intercept

“Blah Blah Bluh Blah”

One of the people I interviewed for this story was Paul Yingling, who, in 2007, became famous in military circles for writing an article titled “A Failure in Generalship.” Yingling was serving as an Army officer at the time and broke the fourth wall of martial protocol by calling out his wartime commanders. In a line that’s been quoted many times since — Miller repeated a variation of it to me — Yingling wrote, “As matters stand now, a private who loses a rifle suffers far greater consequences than a general who loses a war.”

Yingling wasn’t particularly flattered by Miller’s embrace of his idea. Miller is right about the generals, Yingling said, but “much of the criticism he’s made has been made elsewhere earlier and better. … It’s not original work.” That wasn’t Yingling’s main beef with Miller; he was incensed over what he regards as a fellow officer’s involvement in an effort to overturn a presidential election. “I don’t think he is aware of his role to this day,” Yingling said. “He has spun a narrative for himself that justifies his actions on J6. He was in over his head in a political world that to this day he doesn’t understand.”

Yingling mentioned the story of Caligula appointing his horse as a consul in ancient Rome. That myth goes to the strategy of discrediting and disempowering institutions by filling them with incompetent leaders (or beloved equines). And Yingling is certainly right that Trump appointed D-list characters to sensitive positions: the internet troll Richard Grenell as acting director of national intelligence, for instance, and his son-in-law, Jared Kushner, as a senior White House adviser.

It’s also true that the January 6 clusterfuck seems to have had less to do with malignant decisions by Miller than with a parade of errors by officials under his command. As acting secretary of defense, he failed to ensure that his orders at 3:04 p.m. and again at 4:32 p.m. were carried out with greater speed, though Miller says he didn’t want to micromanage his subordinates. There may have been an element of subconscious bias, too.

“I’m African American,” Walker told the committee. “Child of the ’60s. I think it would have been a vastly different response if those were African Americans trying to breach the Capitol.”

Yet I hesitate to ignite the tinder around Miller. If we drop a match at his feet and walk away with a sense of satisfaction about the justice we think we’ve delivered, we have not changed or even recognized the political culture that gave us the forever wars and everything that flowed from them, including January 6. At some point in the future, we’ll just have more of what we’ve already endured, and perhaps it will be a variant of militarism and racism that’s more potent still.

At some point in the future, we’ll just have more of what we’ve already endured, and perhaps it will be a variant of militarism and racism that’s more potent still.

Look, for instance, at who Joe Biden chose to fill the seat kept warm by Miller: Lloyd Austin, a retired general who earned millions of dollars as a board member of defense contractors Raytheon Technologies and Booz Allen Hamilton. Look at Esper, who preceded Miller: He was a lobbyist for Raytheon Technologies, earning more than $1.5 million in salary and bonuses. Look at who came before Esper: Jim Mattis, who was on the board of General Dynamics (as well as Theranos, the fraudulent blood-testing firm). And take a moment to read a few pages of Craig Whitlock’s “The Afghanistan Papers,” which uses government documents to reveal a generation of lies from America’s top generals and officials. The professional interests of these people have been closely connected to exorbitant defense spending and “overseas contingency operations” that account for the U.S. devoting more money to its military than the next nine countries combined — all while school teachers drive Ubers at night and people in Mississippi have to drink bottled water because the municipal system has collapsed.

Where are their bonfires?

A year ago, before Biden’s State of the Union address, Miller joined a press conference outside the Capitol that was organized by the GOP’s far-right Freedom Caucus and featured speakers against mask and vaccine mandates. The last to talk, Miller riffed for seven minutes, saying nothing about Covid-19 and focusing on Afghanistan instead. As he recalled being on a mountainside where an errant American bomb killed nearly two dozen U.S. and Afghan soldiers, a woman behind him shifted with visible unease as he angrily described in graphic terms what you don’t often hear from former Cabinet members: “I stood there and it looked as if someone had taken a pail of ground meat, of hamburger meat, and thrown it onto that hill. And those were the remains of so many who gave their lives on that day.”

Let’s agree, then, that Miller is a bit askew. One of his encounters with reporters in his final days as defense secretary was described by a British correspondent as a “gobsmacking incoherent briefing” that included the phrase “blah blah bluh blah,” according to the Pentagon’s official transcript. But if you’re not askew after going through the mindfuck of the forever wars, there’s probably something wrong with you. It’s an inversion of the “Catch-22” scenario in which the novel’s protagonist, Capt. John Yossarian, tries to be declared insane so that he can get out of the bomber missions that he knows are nearly suicidal, but his desire to get out of them proves he’s sane, so he’s not excused. In an opposite way, generals and politicians who emerge from the carnage of the forever wars without coarse passions, who speak in modulated tones about staying the course and shoveling more money to the Pentagon — they are cracked ones who should not operate the machinery of war.

So here we are, just a few days away from the 20th anniversary of the Iraq invasion on March 19, a cataclysm that killed hundreds of thousands of people, cost trillions of dollars, and began with lies. The Pentagon just decided to name a warship the USS Fallujah, after the city that suffered more violence at the hands of American forces than any other place in Iraq. And Harvard University has just decided to give a prominent position to Meghan O’Sullivan, a Bush administration official who helped design the invasion and occupation of Iraq and since 2017 has been a board member of — you may have heard this one before — Raytheon Technologies (for which she was paid $321,387 in 2021). It’s been 20 years and thanks in part to journalists who were complicit in spreading the first lies and were rewarded professionally for doing so, there has been neither accountability nor learning.

Individual pathologies determine how we medicate ourselves after traumatic events, and I think the politics we choose are forms of medication. Miller opted for service in the Trump administration, and while it strikes me as the least-admirable segment of his life since we met in Kandahar, he’s not an outlier among veterans. For as long as our nation is subordinate to its war machine, we’ll be hearing more from them. Forever wars do not end when soldiers come home.

Discussion about this post