Artist, architect and māmā Raukura Turei loves living centrally, and in community, at Cohaus, the communal housing development in Grey Lynn, Auckland.

Read this story in te reo Māori and English here. / Pānuitia tēnei i te reo Māori me te reo Pākehā ki konei.

Turei, Ngāitai ki Tāmaki, Ngā Rauru Kītahi, lives with her partner, Mokonuiarangi, and their daughter, Hinauri.

RAUKURA TUREI:

Our whānau’s fortunate enough to live at Cohaus, which is in effect a community of like-minded people who, in their choice to be part of a collective development, wanted to join resources, expertise, and what pūtea (money) they had to build a community with a lighter footprint on the earth, all while living centrally.

There are 19 new units in two separate buildings, and the original villa that sat in the centre – once a birthing centre for unwed mothers – remains as a single residence.

READ MORE:

* Paint carver Hikurangi Edwards’ work is a modern spin on Māori carving – and art-buyers are loving it

* At home with sex-positive queer Christian feminist producer and poet Kate Spencer

* At home with photographer, DJ and robot-collector Braden Fastier

I’d owned a house in New Lynn with my ex-partner and I wanted to put that equity into something. The thought of buying a house of my own was daunting.

I love our little community, the fact it’s Grey Lynn where I grew up, still close to my māmā, and it was a way to afford to live back in the very gentrified Grey Lynn it is today.

RICKY WILSON/Stuff

The painted hue (gourds) and clay work is by Moko, a collaboration with Thea Ceramics.

In our whare is also my partner, Moko, and our daughter Hinauri, who’s three.

The seed for joining Cohaus was planted by my now neighbours Biddy and Jym while we were living in Toronto around six years ago, so it’s been a really long collective process.

It was really nice not having to do the architectural work. That was completed by Thom and Helle of Studio Nord, who live here as well. We were informed all the way through, and it always felt like we were in good hands.

RICKY WILSON/Stuff

Turei’s daughter Hinauri is a fluent te reo Māori speaker.

We got to play a role with the architects’ final layout of our unit and the interior finishing. We chose tiles, cabinetry, and added little bits like a skylight in the living room.

All the units wrap around a central garden, and a little common house where we host parties and events. There’s a flourishing productive māra kai (food garden) and those who are interested in gardening put in as much time as they have.

Because I’m stretched between architectural work, painting work, and parenting, I feel the benefit of many hands. Like a modern papakāinga (ancestral home), it’s a model that so many would benefit from.

I’ve made a conscious effort to not work from home. I have designated spaces for my mahi. I work at Monk Mackenzie Architects, where I’m a principal four days a week. I’m leading a few papakāinga projects at the moment – collective housing for and by tangata whenua.

RICKY WILSON/Stuff

The painting is by Nikau Hindin, “a dear friend” of Turei. “We traded works for this at an exhibition we did together.”

Our office is on Quay St, on the waterfront downtown, a beautiful old building we have recently renovated. And then I have a painting studio at the train station in Te Tuhi outpost at Parnell Train Station. I’m no longer attached to a single gallery, but I have recently shown with Bartley and Co in Te Whanga-nui-a-tara, and have a show on now in Sydney at Day01 Gallery.

My painting practice is my space of immediate creative expression where I don’t have to answer to anybody else. It’s experimental and fluid and allows me to get ideas onto paper or linen, without having to conform to the many parameters that architecture has.

RICKY WILSON/Stuff

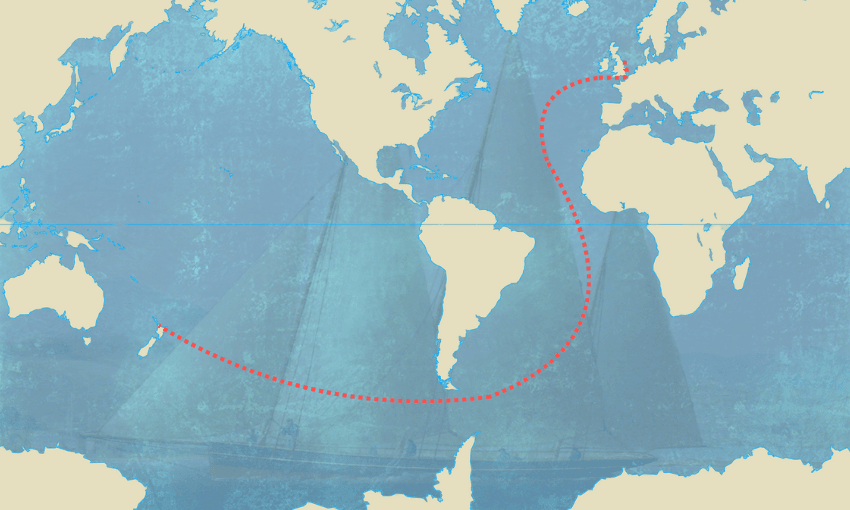

Turei’s own work, a piece from the series Hokinga ki Tīkapa Moana, for which she harvests earth pigments.

It’s a sacred space, my own place to process my own whakaaro and rangahau (research) into atua wāhine (female ancestors) while creating space for stories of whānau members and those who have passed such as my kuia, my father’s mother who I acknowledge in my work. It’s also a space to connect to other Māori artists and to our cultural practice of making earth pigments, where I harvest clays and sands to use in my painting.

The painting has fed into the architecture in that it’s given me more confidence to lean into my taha Māori in my work: Projects that are working with tangata whenua are manifesting themselves in the architecture space.

RICKY WILSON/Stuff

The ceramics have been collected from Turei’s whānau and friends, including Cooper and Clay, Thea Ceramics, Dryburg Studios, Lucy McMillan and Drew Robertson.

Having my daughter has helped distil where I want to put my energy. She’s a little firecracker Scorpio, the lucky recipient of the dreams of my parents’ generation who fought to have te reo Māori recognised as the language of this country. She’s a fluent Māori speaker who’s immersed in it. Of course, she’s picking up English, because how can you not?

I also was fortunate to be raised in te reo. My mum, Jane, who’s Pākehā, made a conscious effort that my siblings and I had Māori education, and she learned with us from birth. It’s a constant journey to keep learning and upskilling and try our hardest to be speaking as much as possible. This process is not an easy one.

There’s a real renaissance at the moment for Māori art, design, and architecture and the need for Māori to see ourselves in the built environment and public spaces.

It’s amazing. It’s about bloody time.

Te Ao

Bic Runga wants more musicians to take the leap to help bilingualism within the industry after releasing her latest te reo Māori song, Kāore He Wā. (First published May 2021.)

Discussion about this post