Research reveals that although H5N1 can infect mice and ferrets through contact with infected milk, it does not easily transmit through the air. This indicates a potential risk to humans handling raw milk, but less concern for wider airborne spread.

Researchers have found that the H5N1

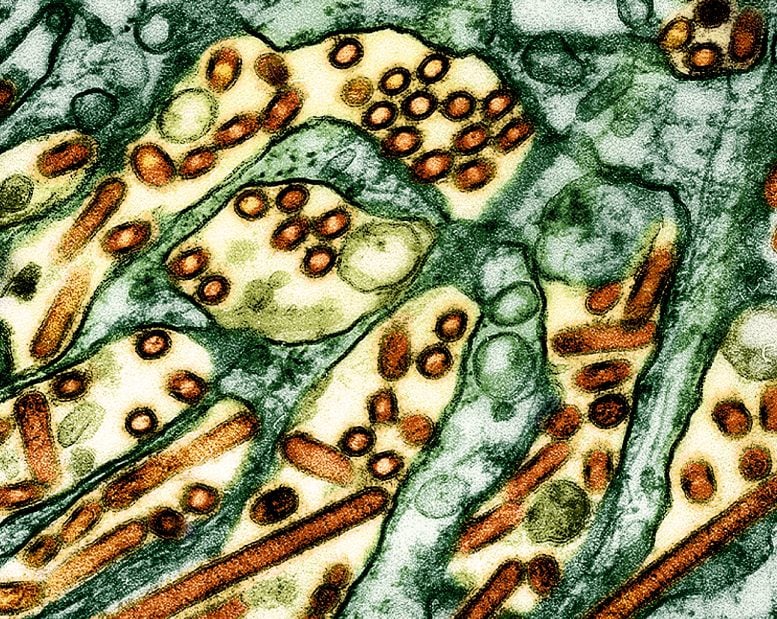

Colorized transmission electron micrograph of avian influenza A H5N1 virus particles (yellow/red), grown in Madin-Darby Canine Kidney (MDCK) epithelial cells. Microscopy by CDC; repositioned and recolored by NIAID. Credit: CDC and NIAID

“This relatively low risk is good news, since it means the virus is unlikely to easily infect others who aren’t exposed to raw infected milk,” says Yoshihiro Kawaoka, a UW–Madison professor of pathobiological sciences who led the study alongside Keith Poulsen, director of the Wisconsin Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory, and with collaborators at Texas A&M University, Japan’s University of Shizuoka and elsewhere.

Kawaoka cautioned, however, that the findings represent the behavior of the virus in mice and ferrets and may not account for the infection and evolution process in humans.

Experimental Results From Animal Studies

In their experiments, the UW–Madison team found that mice can become ill with influenza after drinking even relatively small quantities of raw milk taken from an infected cow in New Mexico.

Yoshihiro Kawaoka, UW–Madison professor of pathobiological sciences. Credit: University of Wisconsin–Madison

Kawaoka and his colleagues also tested the bovine H5N1 virus’s ability to spread through the air by placing ferrets infected with the virus near but out of physical contact with uninfected ferrets. Ferrets are a common model for understanding how influenza viruses might spread among humans because the small mammals exhibit respiratory symptoms similar to humans who are sick with the flu, including congestion, sneezing, and fever. Efficient airborne transmission would signal a serious escalation in the virus’s potential to spark a human pandemic.

None of the four exposed ferrets became ill, and no virus was recovered from them throughout the course of the study. However, upon further testing, the researchers found that one exposed ferret had produced antibodies to the H5N1 virus.

“That suggests that the exposed ferret was infected, indicating some level of airborne transmissibility but not a substantial level,” Kawaoka says.

Findings on Bovine H5N1 Virus’s Adaptability

Separately, the team mixed the bovine H5N1 virus with receptors — molecules the virus binds to in order to enter cells — that are typically recognized by avian or human influenza viruses. They found that bovine H5N1 bound to both types of molecules, representing one more line of evidence of its adaptability to human hosts.

While that adaptability has so far resulted in a limited number of human H5N1 cases, previous influenza viruses that caused human pandemics in 1957 and 1968 did so after developing the ability to bind to receptors bound by human influenza viruses.

Risk Assessment of H5N1 Spread in Livestock

Finally, the UW–Madison team found that the virus spread to the mammary glands and muscles of mice infected with H5N1 virus and that the virus spread from mothers to their pups, likely via infected milk. These findings underscore the potential risks of consuming unpasteurized milk and possibly undercooked beef derived from infected cattle if the virus spreads widely among beef cattle, according to Kawaoka.

“The H5N1 virus currently circulating in cattle has limited capacity to transmit in mammals,” he says. “But we need to monitor and contain this virus to prevent its evolution to one that transmits well in humans.”

For more on this research, see Decoding the Dangerous Jump of H5N1 to Humans.

Reference: “Pathogenicity and transmissibility of bovine H5N1 influenza virus” by Amie J. Eisfeld, Asim Biswas, Lizheng Guan, Chunyang Gu, Tadashi Maemura, Sanja Trifkovic, Tong Wang, Lavanya Babujee, Randall Dahn, Peter J. Halfmann, Tera Barnhardt, Gabriele Neumann, Yasuo Suzuki, Alexis Thompson, Amy K. Swinford, Kiril M. Dimitrov, Keith Poulsen and Yoshihiro Kawaoka, 8 July 2024, Nature.

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-07766-6

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d1/82/d18228f6-d319-4525-bb18-78b829f0791f/mammalevolution_web.jpg)

Discussion about this post