China’s state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are investing in low-carbon sources and helping push the country’s energy transition towards a “critical turning point” where coal power starts to decline, a new report finds.

The report, by thinktank Ember, finds that, in the decade to 2020, central government-controlled power companies (central SOEs) had increased their wind and solar capacity nearly five-fold, surpassing 200 gigawatts (GW).

By 2022 – the most recent data available in the report – central SOEs accounted for about 40% of China’s installed solar capacity and 70% of its wind capacity.

Together with local government-controlled energy firms (local SOEs), these companies have made a “significant contribution” to shrinking coal’s share of China’s electricity mix, which has dropped from more than 70% in 2000 to less than 60% in 2023.

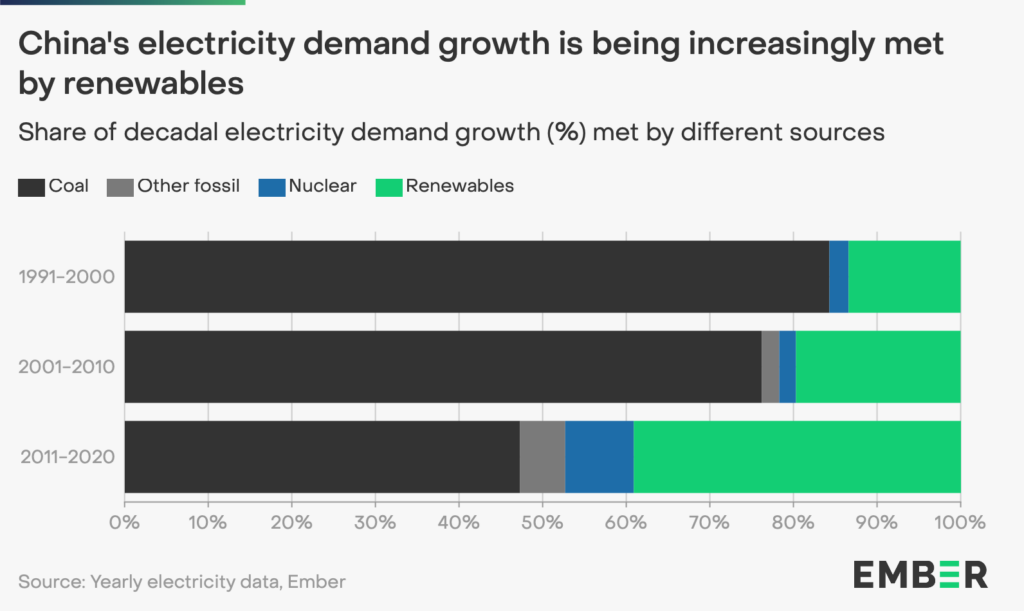

Moreover, coal is contributing less to meeting China’s rising electricity demand, the report says. From 1991-2000, 85% of the incremental electricity demand was met by coal, while in 2011-2020 this figure dropped to only 47%.

The report adds that, if current trends continue, coal power in China “will being to decline in absolute terms”, a turning point that could trigger a reduction in carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from the country’s electricity sector – and its emissions overall.

While SOEs’ diversification strategies have reduced their reliance on coal, however, the report says that these entities remain closely bound up in the “coal-electricity ecosystem”.

As such, the turning point away from coal power could trigger “potential tensions and conflicts” – particularly in coal-reliant regions of the country – that will need to be addressed in order for China’s energy transition to continue.

The transition journey of SOEs

SOEs are organisations set up to carry out commercial activities on behalf of the government.

They play a “crucial role” in China’s economy, particularly in key sectors, such as energy. According to the World Bank, SOEs accounted for 23-28% of China’s GDP in 2017.The leading nine power-sector SOEs are dubbed as “five bigs and four smalls” (五大四小). Collectively, these firms control more than half of China’s electricity generation capacity, as shown in the figure below.

Power-sector SOEs are particularly dominant in terms of the “coal power market (煤电市场)”, Ember notes, with private capital only accounting for a 5% share.

This gives power-sector SOEs a key role in China’s energy transition.

In addition, as a hybrid of corporate organisation and government ministry, SOEs’ development plans closely follow the central government’s overall blueprint.

Their governing body, the state-owned assets supervision and administration commission (SASAC), issued a “guiding opinion” mandate for SOE’s energy transition in 2021, after president Xi Jinping declared the “dual carbon” goal in 2020.

(The “dual carbon” goal is to peak emissions before 2030 and become “carbon neutral” before 2060. Read Carbon Brief’s China country profile for more detail.)

The mandate says that in order to “lay a solid foundation for achieving carbon peak” by 2030, SOEs should “incorporate over 50% of renewable energy in their generation capacity mix by 2025”.

Another recent report, by thinktank Climate Energy Finance (CEF), finds that the “five big” SOEs have poured tens of billions of yuan (billions of dollars) into the buildout of renewable energy, since this document was issued.

With capital expenditure being aligned with energy diversification goals, CEF says all “five bigs” already met the SASAC target in 2023.

Ember’s study on central SOEs finds their wind and solar capacity increased nearly five-folds since 2011, surpassing 200GW in 2020, roughly equivalent to the total installed capacity of Germany.

In 2022, central SOEs accounted for about 40% of China’s solar capacity and 70% of the wind capacity, adds Ember, leading China to approach “a critical turning point in its transition towards a clean electricity future”.

The Ember report says if current trends in energy transition continue, coal power will “begin to decline in absolute terms” – a similar conclusion to recent Carbon Brief analysis.

Pushing down coal’s share

Coal’s share of China’s electricity generation is declining. As shown in the figure below, coal’s share (black) dropped from nearly 80% in 2000 to about 60% in 2023.

(It fell further still, to a record-low 53% in May 2024, according to Carbon Brief analysis.)

Meanwhile, the combined share of wind (dark green) and solar (light green) grew from about 4% in 2015 to almost 16% in 2023, says Ember.

In addition, the role of coal in meeting the growing electricity demand is diminishing, as shown in the figure below.

Ember finds about 85% of the incremental electricity demand from 1991-2000 was met by coal (black), falling to 76% in the decade to 2010 and only 47% in the decade to 2020.

The contribution of renewable energy (green), including wind, solar, hydro, bioenergy and other sources, steadily increased over the same time period.

In 2023, China’s demand for electricity grew 6.7% compared to the previous year – higher than the average annual demand growth of about 6% between 2013 and 2022.

Ember says that, although hydropower decreased by about 59 terawatt hours (TWh) in 2023, wind and solar met 46% of the increased demand, followed by bioenergy and nuclear.

“If hydro had remained at 2022 levels, non-fossil fuel generation would have met more than half of the demand increase in 2023, further pushing coal power out of the generation mix,” adds the report.

(Carbon Brief’s previous analysis shows the decline of hydropower was due to a series of droughts in 2022/23.)

Muyi Yang, author of the Ember report, tells Carbon Brief that the surge in low-carbon energy means an “absolute decline” in coal power is “very likely to soon begin”.

Yang also thinks “the recent announcement of the ‘coal power low-carbon retrofitting action plan’ signifies that China has started to prepare for the new era of coal generation”.

The action plan, released by China’s top planner National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), is allocated to a number of SOEs, including the “five bigs”.

However, the Shuang Tan newsletter says the action plan is designed “to test the selected technologies at a few carefully chosen [SOE] coal power units”. Moreover, since the action plan did not set a “performance target”, it is “unlikely to drive industry-wide transformation”, adds the newsletter.

‘Crossing the river by touching the stones’

Despite the progress to date in diversifying China’s electricity supply – and the business models of the country’s power sector SOEs – major challenges lie ahead, Ember says.

A number of central SOEs also have major interests in other parts of the coal ecosystem.

Central SOE China Shenhua, for example, spent 8bn yuan (about $1bn) on coal mining development and exploration, and only 824m yuan (about $113m) in hydropower in the first half of 2023, according to a report by CEF.

Nevertheless, Shenhua parent company CHN Energy’s overall portfolio still complies with SASAC’s general energy diversification goal, CEF says. This is largely due to another subsidiary – Longyuan Power – being one of the largest wind power companies in China.

The Ember report explains:

“This [coal-electricity] ecosystem is characterised by extensive cross-industry and cross-ownership linkages encompassing coal production and supply, logistics, the coal chemical industry, power generation and the manufacturing of related equipment and facilities. Consequently, an absolute decline in coal generation will inevitably impact other interconnected and interdependent segments of this system, with far-reaching ramifications, particularly within the broader socio-economic assemblages that have evolved around it.”

“Reduced coal generation presents substantial challenges”, says Yang, “economic restructuring, including switching to ‘green industry’, will require comprehensive support”.

The challenges are more significant in major coal-producing provinces, such as Shanxi. In 2022, coal and its related industry contributed 80% of tax revenues and provided 55% local jobs for the province, according to Chinese financial media outlet Caixin.

Ember says that this illustrates why diversification of power-sector SOEs is, on its own, insufficient. It explains:

“Diversification strategy by large generation SOEs is useful, as it weakens the incumbent utilities’ commitment to the existing coal-dominated power system, making deeper transition…possible. However, its effectiveness begins to wane when considering its inability to adequately address the tensions and conflicts that may arise from the absolute decline in coal power and the wider impacts associated with it.”

The report continues by suggesting that coal-dependent regions will also need to develop tailored diversification strategies to address the “unique challenges” they face. It says:

“By diversifying the economic base of these areas, a smoother transition can be facilitated, mitigating the adverse effects on local communities and workers who have long relied on the coal-electricity sectors.”

Yet challenges remain, Ember says, because clean-energy industries may not bring benefits to the same regions that have long relied on coal.

Yang says “the key issue here is not about the magnitude of the benefits [of renewable energy], but their distribution”. He adds:

“Many modelling studies have confirmed that the clean energy transition is beneficial and can create growth and jobs, more than sufficient to offset reduced economic activities from conventional fossil fuel supply chains.

“By leveraging their substantial resources and infrastructure, SOEs can lead the development and integration of renewable energy projects, enhance grid stability, and ensure a reliable energy supply.”

Finally, the report suggests that China takes the path of “gradualism and experimentation” to navigate the challenges inherent in the transition away from coal. It says:

“Often likened to ‘crossing the river by touching the stones’, these approaches are widely recognised as pivotal to China’s economic success. They allow for careful testing and adjustment of strategies and policies, facilitating the adaptation of broader policy directives into pragmatic, localised actions tailored to specific circumstances. Additionally, they help promote consensus-building among a diverse range of stakeholders by incorporating iterative improvements based on practical experience and feedback.”

Sharelines from this story

Discussion about this post