Detroit’s city council will soon vote on whether to spend millions in federal cash meant to ease the economic pains of the coronavirus pandemic on ShotSpotter, a controversial surveillance technology critics say is invasive, discriminatory, and fundamentally broken.

ShotSpotter purports to do one thing very well: telling cops a gun has been fired as soon as the trigger is pulled. Using a network of microphones hitched to telephone poles, rooftops, and other urban vantage points, ShotSpotter is essentially an Alexa that listens for a bang rather than voice commands. Once the company’s black-box algorithm thinks it has identified a gunshot, it sends a recording of the sound — and the moments preceding and following it — to a team of human analysts. If these ShotSpotter staffers agree the loud noise in question is a gunshot, they relay an alert and location coordinates to police for investigation.

At least, that’s the pitch. Despite ShotSpotter’s corporate claims of 97 percent accuracy, the technology’s efficacy has been derided as dangerously ineffective — a techno-solutionist approach to public safety. Critics contend that the system draws police scrutiny to already over-policed areas using a proprietary, secret sound detection algorithm. The technology, according to reports, regularly mistakes city noises, including fireworks and cars for gunshots, ignores actual gunshots, provides misleading evidence to prosecutors, and is subject to biases because ShotSpotter employees at times manually alter the algorithm’s findings.

Detroit already has a $1.5 million contract with ShotSpotter, a California company, to deploy the microphones in select areas, but city officials, including Mayor Mike Duggan, insist that substantially expanding the audio surveillance network will deter gun slayings. The plan is set to go to a vote before the full city council on September 20, and local organizers are opposing the use of money meant for economic relief to expand city security contracts and beef up police surveillance.

“The Biden administration passed the American Rescue Plan and put forth this Covid relief money to inject money into local economies and to get people back on their feet after the pandemic,” said Branden Snyder, co-director of Detroit Action, a community advocacy group that opposes the vote. “And this is doing the opposite of that. What it does is fatten the wallets of ShotSpotter.”

Cities across the country are tapping federal recovery money to add or broaden ShotSpotter systems, NBC News reported earlier this year. Syracuse, New York, for instance, spent $171,000 on ShotSpotter, and Albuquerque, New Mexico, paid the company $3 million from the recovery fund. Should the vote pass, Detroit would be the biggest of these customers using Covid relief funds, both in terms of population and the proposed price tag for the surveillance expansion.

ShotSpotter spokesperson Izzy Olive pointed to remarks by President Joe Biden encouraging local governments to use flexible relief funds to beef up police departments. “Some cities have chosen to use a portion of these funds for ShotSpotter’s technology,” she said. The company claims that more than 125 cities and police departments use the system and that it guarantees 90 percent efficacy within some basic parameters, according to self-reported data from police compiled by the company. Asked about Detroit’s system, Olive said the city owns the data collected by ShotSpotter. She did not comment on whether the company restricts what cities can say about it, saying only that “the contract itself is not confidential.”

ShotSpotter’s opponents in Detroit agreed that gun violence is a serious problem but said Covid-19 relief money would be far better spent on addressing the social ills that form the basis of crime.

“What it does is fatten the wallets of ShotSpotter.”

“If people had jobs, money, after-school programs, housing, the things that they need, that’s going to reduce gun violence,” said Alyx Goodwin, a campaign organizer with Action Center on Race and the Economy.

Snyder pointed to the fundamental irony of diverting public money billed as form of relief for the pandemic’s downtrodden to surveil those very same people.

“The reason why we’re in these policing fights, as an economic justice organization, is that our members are folks who are looking for housing, rental support, looking for job access,” Snyder said. “And what we’re given instead is surveillance technology.”

Duggan’s case for expanding the ShotSpotter contract kicked into high gear in late August when, following a mass shooting, he claimed that police could have thwarted the killings had a broader surveillance net been in place. “They very likely could have prevented two and probably three tragedies had they had an immediate notice,” Duggan said.

The mayor’s claims echo those of the company itself, which positions the product as an antidote to rising national gun violence rates, particularly since the onset of the pandemic. ShotSpotter explicitly urges cities to tap funds from the American Rescue Plan Act, intended to salve financial hardship caused by the pandemic, to buy new surveillance microphones.

“As the U.S. recovers from COVID-19, gun crime is surging to historically high levels,” reads a company post titled “The American Rescue Act Can Help Your Agency Fund Crime Reducing Technology.” The post refers interested municipalities to a company portal that lists resources to help navigate the procurement process, adorned with an image of a giant pile of cash, including a “FREE funding consultation with an expert who knows the process.”

ShotSpotter even published a video webinar guiding police through the process of obtaining Covid money to buy the surveillance tech. In the video, the company’s Director of Public Safety Solutions Ron Teachman offers to personally connect interested parties with ShotSpotter’s go-to expert on federal funding, consultant and former congressional aide Amanda Wood.

Teachman and Wood say in the video that ShotSpotter will furnish eager police with pre-drafted language to help pitch relevant elected officials. “I know you all understand the value of ShotSpotter and that’s why you’re here, but if there are other folks in your community who don’t understand it, we’re happy to sort of spoon-feed them that information,” Wood says. “We have broad language, and we can really personalize it for whatever you need.” (Olive, the ShotSpotter spokesperson, said the company was sharing publicly available information and did not comment on what efforts the company made to guide Detroit through the process of applying for funds.)

Wood also suggests that police enlist local groups, from grassroots organizations to medical administrators, to help with the pitch. “Those hospital CEOs are pretty well connected. So let’s use them, let’s leverage their relationships so that they’re echoing the same sort of messaging that you are … put a little pressure on those electeds and administrators.”

Overall, the use of federal Covid money to buy microphones is described as a cakewalk. In the webinar, Teachman says, “This is as easy a federal funding source as I’ve seen.”

Despite the objections from community groups, Biden himself outlined uses like this for Covid relief funds. “Mayors will also be able to buy crime-fighting technologies, like gunshot detection systems,” Biden said in a June 2021 address on gun violence.

Billions in Covid aid have been spent on funding police departments, a flood of money that’s proven a boon to surveillance contractors, said Matthew Guariglia, a policy analyst with the Electronic Frontier Foundation. “For a long time already, money that has been intended for public well-being has been specifically funneled into police departments,” said Guariglia, “and specifically for surveillance equipment that maybe they didn’t have the money to fund beforehand.”

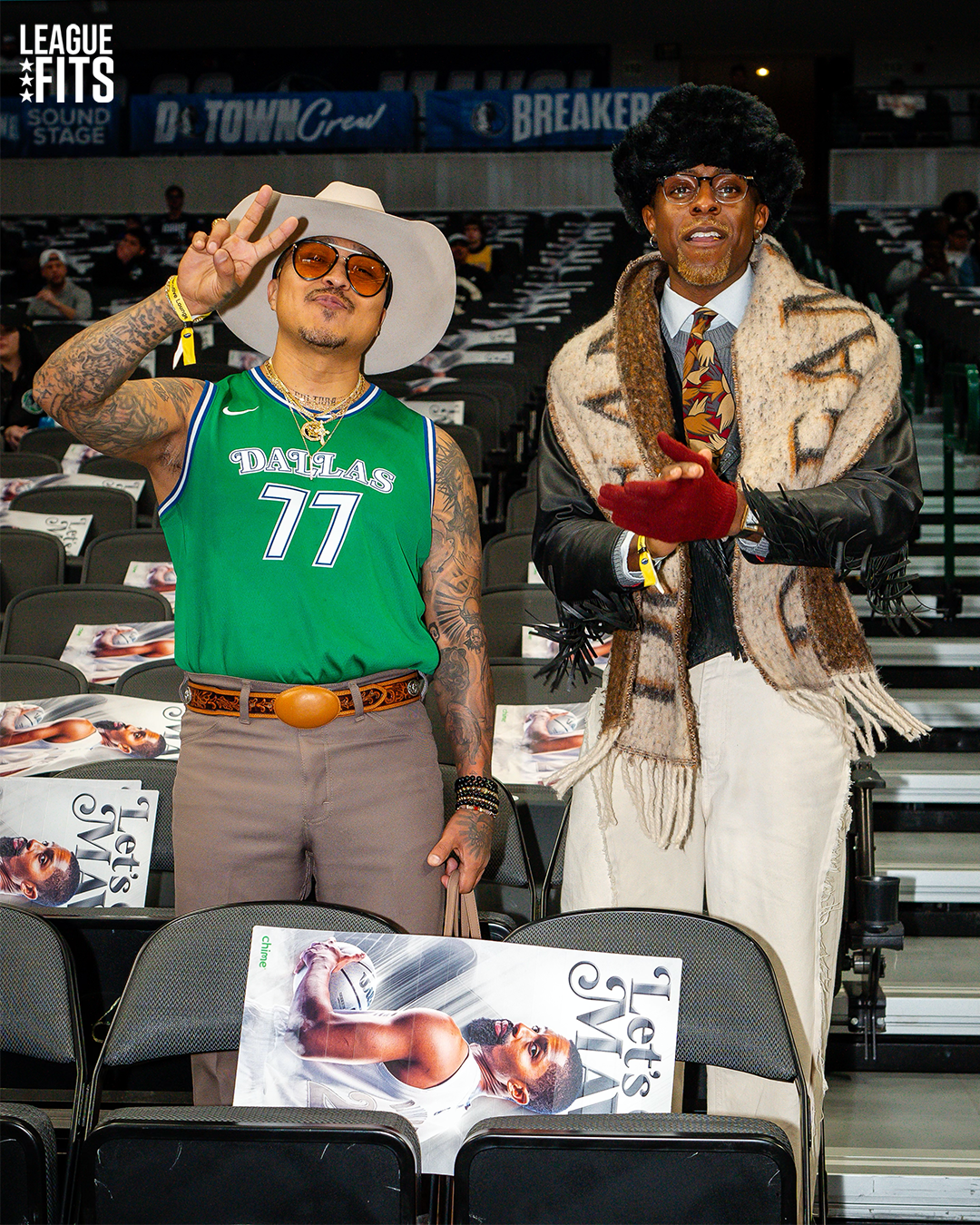

ShotSpotter equipment overlooks the intersection of South Stony Island Avenue and East 63rd Street in Chicago, on Aug. 10, 2021.

Photo: Charles Rex Arbogast/AP

Critics of Detroit’s plan said ShotSpotter doesn’t stop gun violence and exacerbates over-policing of the same struggling neighborhoods the Covid relief money was meant to help. A study published last year by Northwestern University’s MacArthur Justice Center surveyed 21 months of city data on ShotSpotter-based police deployments and “found that 89% turned up no gun-related crime and 86% led to no report of any crime at all. In less than two years, there were more than 40,000 dead-end ShotSpotter deployments.”

City government data from Chicago and other locations using ShotSpotter revealed the same pattern over and over, according to the MacArthur Justice Center. In Atlanta, only 3 percent of ShotSpotter alerts resulted in police finding shell casings. In Dayton, Ohio, another ShotSpotter customer, “only 5% of ShotSpotter alerts led police to report incidents of any crime.” A series of academic studies into ShotSpotter’s efficacy reached the same conclusion: Loud noise alerts don’t result in fewer gun killings.

“People don’t want gunshots in their neighborhood, period. And a microphone does not stop the gunshot.”

Not only is ShotSpotter a waste of money, critics say, but the system menaces the very neighborhoods it claims to protect by directing armed, keyed-up police onto city blocks with the expectation of a violent confrontation. These heightened police responses occur along stark racial lines. “In Chicago, ShotSpotter is only deployed in the police districts with the highest proportion of Black and Latinx residents,” the MacArthur Justice Center found, pointing to a Chicago inspector general’s report that found ShotSpotter alerts resulted in more than 2,400 stop-and-frisks. A 2021 investigation by Motherboard found that “ShotSpotter frequently generates false alerts—and it’s deployed almost exclusively in non-white neighborhoods.”

The concern is not hypothetical: A March 2021 ShotSpotter-triggered Chicago deployment resulted in the fatal police shooting of an unarmed 13-year-old boy, Adam Toledo. “If you have police showing up to the site of every loud noise, guns drawn, expecting a firefight, that puts a lot of pedestrians, a lot of people who lives in neighborhoods where there are loud noises, in danger,” Guariglia said.

ShotSpotter’s claims of turn-key functionality and deterrent effect are tempting for mayors like Detroit’s Duggan, according to Snyder of Detroit Action. The politicians are eager to project a “tough on crime” image as gun violence has spiked during the pandemic. Yet Snyder said that ShotSpotter’s limited trial in Detroit has so far proven ineffective. “It actually hasn’t led to any sort of like real, significant arrests,” he said. “It actually hasn’t produced that type of success that I think many elected officials as well as the company itself are spouting.”

An infographic created by the city claims that “ShotSpotter is saving lives!” and cites a downward trend in fatal shootings in neighborhoods where the equipment is installed. The infographic, though, provides no evidence that the technology itself was responsible for this decline and provides only one example of a ShotSpotter alert leading to a gun-related conviction in the city.

“ShotSpotter doesn’t stop gunshots from happening,” said Goodwin of the Action Center on Race and the Economy. “People don’t want gunshots in their neighborhood, period. And a microphone does not stop the gunshot.”

Discussion about this post