By

Located in the foothills of Mount Elgon near the Kenya-Uganda border, Kakapel Rockshelter is the site where WashU archaeologist Natalie Mueller and her collaborators have uncovered the earliest evidence for plant farming in east Africa. Credit: Steven Goldstein

Recent findings from Kenya’s Kakapel Rockshelter highlight the origins and development of ancient farming in East Africa, detailing the introduction of crops like cowpea and challenging past perceptions of African agriculture.

A trove of ancient plant remains unearthed in Kenya sheds light on the history of crop farming in equatorial eastern Africa. This region has been considered significant for early agricultural development, yet there has been little physical evidence of ancient crops found there until now.

In a new study recently published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B, archaeologists from Washington University in St. Louis, the University of Pittsburgh, and their colleagues report the largest and most extensively dated archaeobotanical record from interior east Africa.

Up until now, scientists have had virtually no success in gathering ancient plant remains from east Africa and, as a result, have had little idea where and how early plant farming got its start in the large and diverse area comprising Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda.

“There are many narratives about how agriculture began in east Africa, but there’s not a lot of direct evidence of the plants themselves,” said WashU’s Natalie Mueller, an assistant professor of archaeology in Arts & Sciences and co-first author of the new study. The work was conducted at the Kakapel Rockshelter in the Lake Victoria region of Kenya.

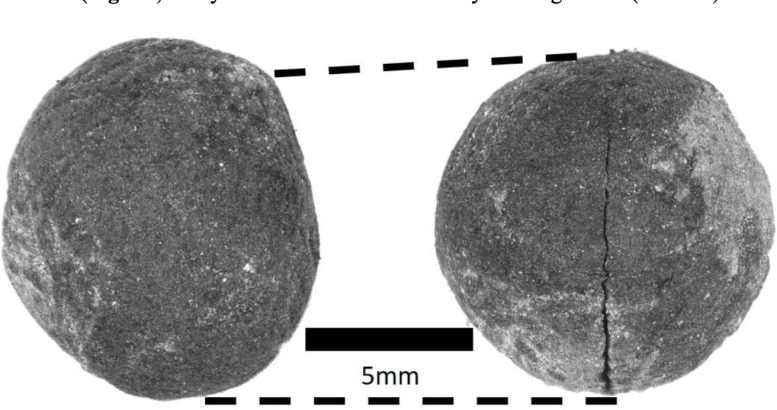

One unusual crop that Mueller uncovered was field pea, burnt but perfectly intact. Peas were not previously considered to be part of early agriculture in this region. Credit: Courtesy of Proc. Royal Soc. B

“We found a huge assemblage of plants, including a lot of crop remains,” Mueller said. “The past shows a rich history of diverse and flexible farming systems in the region, in opposition to modern stereotypes about Africa.”

The new research reveals a pattern of gradual introductions of different crops that originated from different parts of Africa.

In particular, the remnants of cowpea discovered at Kakapel rock shelter and directly dated to 2,300 years ago constitute the earliest documented arrival of a domesticated crop — and presumably of farming lifeways — to eastern Africa. Cowpea is assumed to have originated in west Africa and to have arrived in the Lake Victoria basin concurrent with the spread of Bantu-speaking peoples migrating from central Africa, the study authors said.

“Our findings at Kakapel reveal the earliest evidence of domesticated crops in east Africa, reflecting the dynamic interactions between local herders and incoming Bantu-speaking farmers,” said Emmanuel Ndiema from the National Museums of Kenya, a project partner. “This study exemplifies National Museums of Kenya’s commitment to uncovering the deep historical roots of Kenya’s agricultural heritage and fostering an appreciation of how past human adaptations can inform future food security and environmental sustainability.”

Constantly changing landscape

Situated north of Lake Victoria, in the foothills of Mount Elgon near the Kenya-Uganda border, Kakapel is a recognized rock art site that contains archaeological artifacts that reflect more than 9,000 years of human occupation in the region. The site has been recognized as a Kenyan national monument since 2004.

“Kakapel Rockshelter is one of the only sites in the region where we can see such a long sequence of occupation by so many diverse communities,” said Steven T. Goldstein, an anthropological archaeologist at the University of Pittsburgh (WashU PhD ’17), the other first author of this study. “Using our innovative approaches to excavation, we have been uniquely able to detect the arrival of domesticated plants and animals into Kenya and study the impacts of these introductions on local environments, human technology and sociocultural systems.”

Mueller first joined Goldstein and National Museums of Kenya to conduct excavations at the Kakapel Rockshelter site in 2018. Their work is ongoing. Mueller is the lead scientist for plant investigations at Kakapel; the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology (in Jena, Germany) is another partner on the project.

Mueller used a flotation technique to separate remnants of wild and domesticated plant DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2023.2747

Discussion about this post