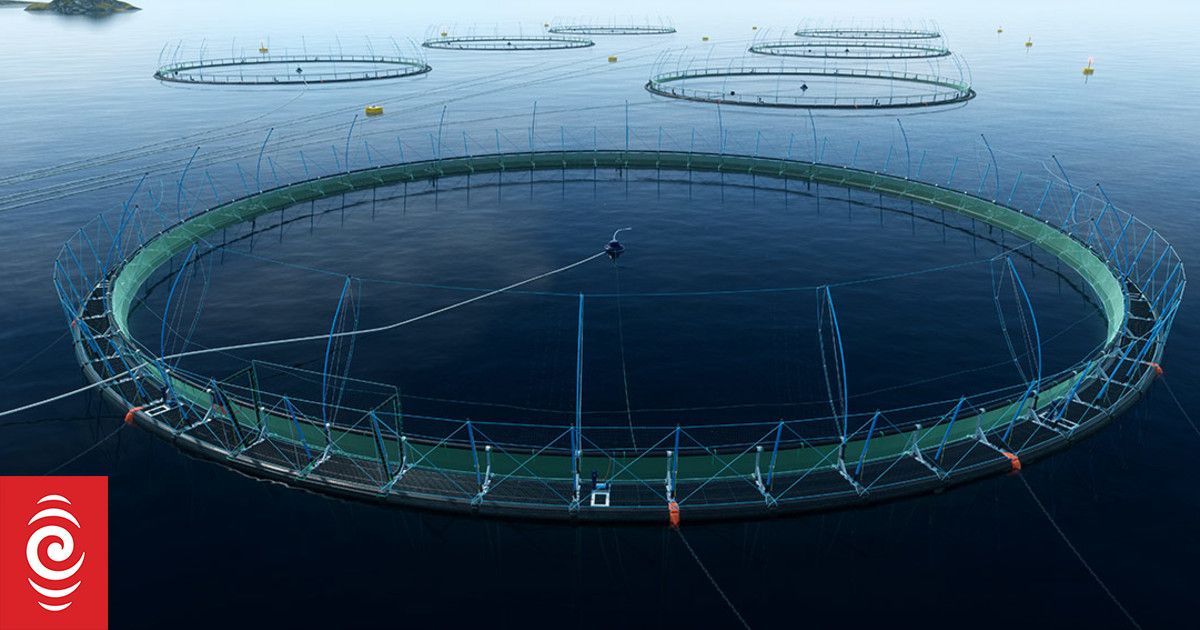

An artist’s impression of the Blue Endeavour ocean farm being planned by NZ King Salmon.

Photo: NZ King Salmon

A plan for the country’s first open ocean salmon farm is facing another hurdle, after two organisations lodged appeals against the decision.

New Zealand King Salmon got resource consent last month for its Cook Strait project – but the Department of Conservation and Wellington-based think tank McGuiness Institute are appealing the decision.

The country’s biggest salmon producer, New Zealand King Salmon said it will start negotiations with both parties in the new year.

Last summer, more than 12,000 tonnes of dead salmon and fish waste were trucked out of the Marlborough Sounds, as a marine heatwave led to record mortalities on King Salmon’s farms.

It forced the country’s biggest salmon producer to fallow three farms in the Pelorus Sound.

Acting chief executive Graeme Tregida said this summer’s water temperatures were expected to be just as warm, if not warmer, than the last.

“What we’re looking for, is cooler waters, higher flow and as those waters have been warming in this region, and no less so this year with a marine heatwave, moving out into the outer ocean is the place to go.”

That was what they hoped to gain with the Blue Endeavour farm which will be located off Cape Lambert in the outer Marlborough Sounds.

“After last year we changed our farming model and we do not have any of our production fish based in any of the lower flow or warmer water sites. So our only harvest fish available right now is in cooler waters, mostly in the Tory channel,” Tregida said.

Developing open ocean farming is part of a government strategy to grow the aquaculture industry from $600 million in sales in 2018 to $3 billion by 2035.

Fisheries New Zealand’s Mat Bartholomew said there were three other applications underway for open ocean finfish farms in Aotearoa – with Blue Endeavour the first to have gained consent.

“That single farm could produce up to 10,000 tons of salmon and so that would be one-eighth of the growth that we’re looking to achieve and while the area consented looks large, the actual area that would be used for farming is quite small.

“So we think that when you look around New Zealand’s extensive marine estate that we can find those areas, we can have another five, six or seven farms of a similar scale.”

A report to Fisheries NZ estimates salmon farming could generate $1.5b in revenue, if production could increase from the current level of around 15,000 tonnes to 80,0000 tonnes a year.

“The question comes can New Zealand do it in a way that upholds our values that deliver sustainable growth, and delivers a high value product and we think that is the case,” Bartholomew said.

NZ King Salmon’s Te Pangu Bay farm.

Photo: Supplied/ NZ King Salmon

Forsyth Barr equity analyst Margaret Bei who follows New Zealand King Salmon said there was a degree of uncertainty around the project.

“What’s interesting in this case is that open ocean aquaculture hasn’t actually been tested before in New Zealand so the two key questions are whether fish health will be improved and how the infrastructure of the pens will hold up under the conditions at the proposed site.”

Bei said the costs and timing of the project were also unknown, along with how it will be funded.

McGuiness Institute chief executive Wendy McGuiness said it was appealing the consent due to concerns over the open ocean farming model and the potential for pollution, the risks it posed to wildlife and reduced access.

“King Salmon basically have a right under this consent to use 1000 hectares [for marine farming] that no one else is allowed to use.

“It’s a little bit like giving a farmer free land to pollute and use for 35 years and them not ever paying anything for it.”

A spokesperson for the Department of Conservation said it was seeking amendments to certain conditions of the resource consent related to the monitoring of benthic effects, including the content of monitoring plans to be developed by NZ King Salmon and the process for a benthic monitoring plan certification to be undertaken by Marlborough District Council.

The spokesperson said DOC was hopeful an agreed outcome would be reached at mediation.

Discussion about this post