August 27, 2024

4 min read

Why Aging Comes in Dramatic Waves in Our 40s and 60s

A new study suggests that waves of aging-related changes occur at two distinct points in our life

Bob_Bosewell/Getty Images

As a person enters their 60s, it’s common for them to start really feeling the health effects of aging. Many people might need glasses or hearing aids, or their doctors may warn them about a sharply increased risk of diabetes or heart disease. But new research published this month suggests that our body tends to undergo a dramatic wave of age-related molecular changes not only in our 60s but also in our mid-40s.

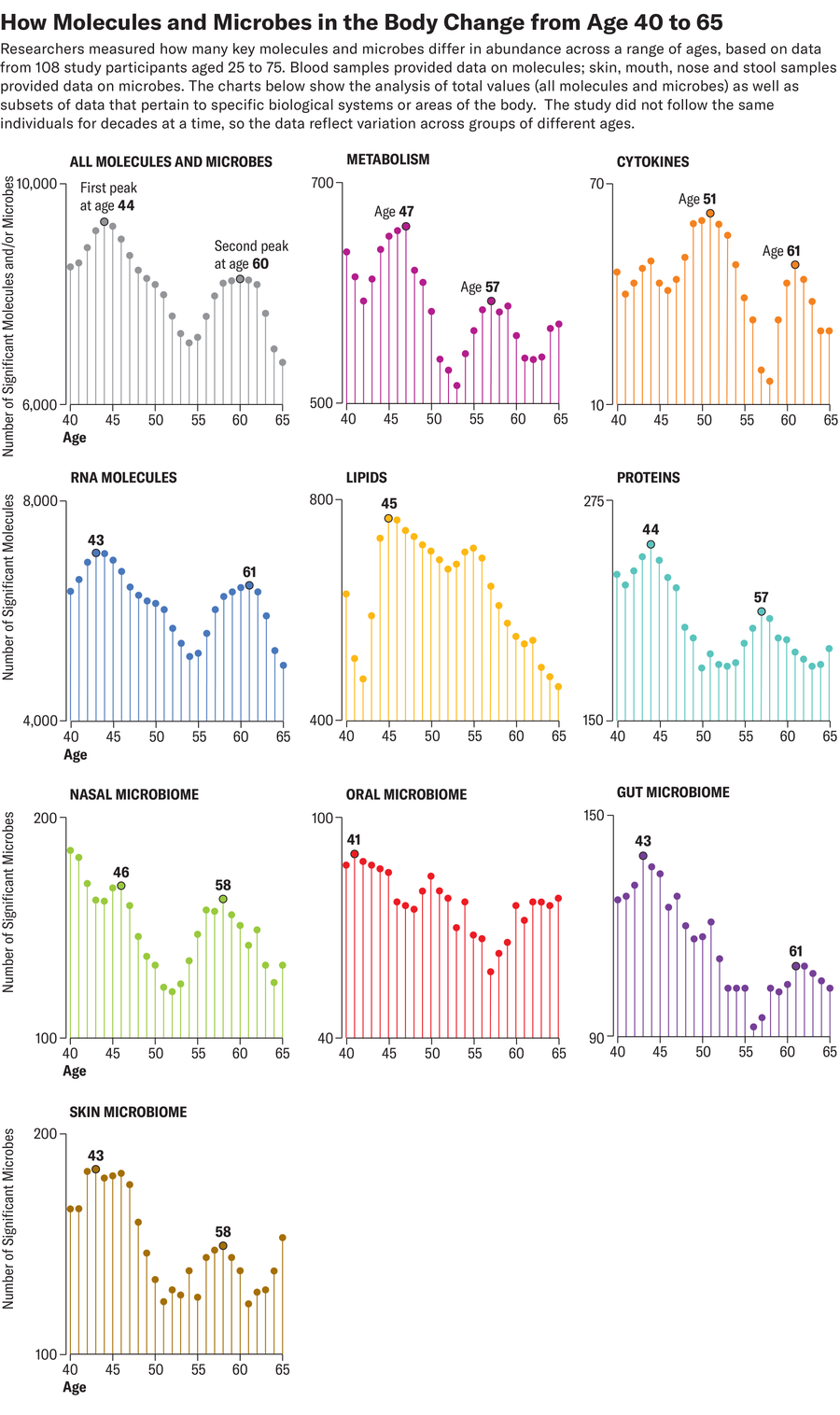

For a study in Nature Aging, researchers tracked the levels of more than 135,000 molecules and microbes, all reflective of activity in cells and tissues, in 108 healthy volunteers aged 25 to 75. Each volunteer contributed biological specimens, including blood and stool samples, every three to six months for a median of 1.7 years. Results showed that differences in the levels of many molecules and microbes clustered around two distinct time points: age 44 and 60. The findings suggest that aging might accelerate around those periods—and signal to experts that our 40s and 50s may be a significant period to closely monitor health.

The study also supports many people’s anecdotal reports of noticing changes that range from more muscle injuries to worse hangovers in their 40s—and the data give clues as to why, says senior study author Michael Snyder, a genetics researcher at Stanford Medicine.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Compared with younger participants, people in their 40s and 60s displayed biological differences that appeared to be linked to muscle weakness and loss, declines in heart health and inefficient caffeine metabolism. Those in their 40s also had less activity in cellular pathways responsible for breaking down alcohol and fats—possibly a sign that people may start to digest these compounds more slowly around this age. People in their 60s, meanwhile, had lower levels of various immune system molecules, such as inflammatory cytokines, which corresponded to a weakened immune response. They also showed significant differences in levels of certain molecules associated with carbohydrate digestion and heart and kidney function, suggesting that the older participants were more susceptible to type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and kidney issues.

The new study’s time points are similar to those identified in a separate 2020 study that found that the immune systems of participants grew markedly less adept at fighting off pathogens around age 35 and again around age 65. But the latest study’s findings are not ironclad; it sampled a relatively small number of people, all living in California’s Palo Alto area. The resulting lack of geographic diversity in the participants makes the data less representative of the broader public, notes Aditi Gurkar, who conducts aging-related research at the University of Pittsburgh and was not involved in the recent study. Study participants likely had some lifestyle factors in common, such as diet, exercise and environmental exposures, which could have swayed the results, she says.

The study also did not follow any individual participants for periods longer than about seven years, so scientists cannot be certain that differences between people in different age groups reflect universal changes. For example, the 40- and 60-year-olds in the study may have aged faster relative to others of the same age in the broader population, Gurkar cautions. She and others say the best way to confirm the results—and to precisely trace age-related biological shifts—would be through a larger study that tracks the same participants over the course of a lifespan. Collecting data on factors such as disease status, physical function or disability could also help better assess the extent to which age-related shifts affect a person’s overall health. (The amount of stress that cells and tissues undergo—what researchers refer to as “biological aging”—varies widely between people of different races and socioeconomic classes, and it even differs between individual organs in a person’s body.)

The reasons why the ages of 44 and 60 might be turning points in health are not yet apparent, but the study authors hope to probe several hypotheses in future work. Snyder suspects that for people in their 60s, declines in immune system function might precipitate a more widespread breakdown of organs. A midlife decline in physical activity, meanwhile, could explain the differences seen among participants in their 40s—but so might hormonal changes, including menopause. Menopause alone, however, could not explain the trends in the study, Snyder says. Male and female participants appeared to show the same degree of age-related differences at both time points.

Snyder thinks the new data can provide actionable health information. People in their 40s might benefit from getting blood tests that track lipid levels, for instance, or from exercising regularly to maintain heart health. Snyder also underscores the importance of early and regular screenings for heart disease for people in this age range who have existing health conditions.

The new study may have limitations, but it is still a powerful reminder that lifestyle choices such as diet and exercise can accelerate aging—or slow it down, Gurkar says. Few studies on aging focus on middle-aged participants or involve biological sampling as comprehensive as that of this new paper, she adds. And in addition to identifying potential waves of age-related changes, the work provides a crucial first step toward one day building large-scale disease prediction models based on biological data.

Discussion about this post