Almost every month, the national police, customs services and the Congolese Institute for the Conservation of Nature (ICCN) conduct seizures of protected wildlife species and ivory. Border posts, car parks, airports, ports, hotels and private homes are among the places where these seizures are reported in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

But, because of corruption and the lack of adequate mechanisms for storage and traceability, these objects remain for lengthy periods on the premises of the institutions that seized them, exposing them to repeat thefts by traffickers.

To put an end to this situation, wildlife protection activists are urging the government to create several reserves to accommodate rescued wildlife, strengthen the security of existing reserves, and start burning ivory and other seized wildlife items to prevent them from returning into the illegal circuit.

Record seizure

One of the record seizures was recorded at Uvira in South Kivu province in December 2022. Almost half a tonne of ivory — equivalent to about 20 elephants slaughtered — was seized and two suspects were arrested, according to officials at Kahuzi Biega National Park.

Some of the ivory bore markings (place, weight and date), suggesting they were objects stolen from a stockpile somewhere in the DRC — the subject of a previous seizure or storage.

Traffickers also sometimes use fake permits or mark the ivory themselves in an attempt to deceive officials that it was part of an authorised operation, according to an environmental activist based in Uvira, who asked for anonymity to protect himself.

Despite the arrests, the destination of the seized ivory is not known, said Josué Aruna, president of the environmental civil society of South Kivu. “In this case, it is likely to return to the black market, since nothing has been heard about the destination. Nothing indicates that it was handed over to the ICCN, or transferred to Kinshasa [the capital],” Aruna said.

In July 2021 in Butembo, a large urban centre located near the Virunga National Park in the province of North Kivu, an operation by ICCN to shadow an alleged poacher failed. As a result about 50kg of ivory ended up in the hands of local inhabitants, according to police estimates.

In Lubumbashi, further south in the province of Haut Katanga, baby chimpanzees were stolen from a sanctuary. The kidnappers demanded$200,000 from the sanctuary owner before handing over the animals.

Armed groups

Examples multiply where police stations or ranger patrol posts are attacked and dispossessed of seized objects, or even release detainees including poachers and traffickers. These attacks are reportedly the work of local and foreign armed groups that are active in and near national parks and protected areas in the DRC.

Since the end of 2022, the southern part of Virunga National Park has been largely under the control of the M23 rebels as well as the Nyantura police. As a result, monitoring of the gorilla groups has stopped.

This lack of surveillance increases poaching and exposes baby gorillas to trapping by poachers, worries Bienvenu Bwende, who is in charge of communication at Virunga National Park. He added that in the centre of the park the Mai Mai and FDLR (Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda) militias attack the park’s fauna and flora, while in the north there is the threat of the ADF (Allied Democratic Forces) rebel group.

Kivu Security Tracker, a project of New York University’s Congo Study Group and Human Rights Watch, lists more than half a dozen armed groups that practise illegal cross-border trade between the DRC and Uganda. Revenues generated by trafficking of the park’s natural resources are estimated at $175-million a year, and more than 100 000 people derive a direct livelihood from these illegal activities.

Between 2017 and 2020, an estimated $50 million contributed to the enrichment of militias and armed groups, according to the tracker.

Security systems

Effective security systems are lacking in the DRC’s reserves and other protected areas. Sanctuaries managed by private individuals organise their own security, and national parks are protected by often understaffed and ill-equipped eco-guards. This predisposes them to intrusions by poachers from armed groups, illegal miners and loggers, and wildlife traffickers. Some authorities are also part of these illegal groups.

Anicet (an alias) has trafficked in elephant tusks. In a village located in the Beni territory, North Kivu province near Virunga National Park, he is known as a butcher specialising in the sale of beef. He testifies that, given the resemblance between ox horns and ivory, it is easy to pass one off as the other without being detected by the police or other state services.

“To move our herds, we leave at night to allow the animals to move long distances without getting tired. I took the opportunity more than once to transport ivory to big cities like Butembo without anyone noticing,” said this man in his 40s.

During the 18th session of the Conference of the Parties for the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, held in Sri Lanka in 2019, CITES said it is “aware of a number of thefts of ivory from government-held stockpiles in recent years” around the world.

Decentralised management

National efforts to combat poaching and the illegal trade in wildlife products are hindered by decentralised management of existing ivory stocks and challenges in tracing the origins of some stocks. A 2020 report by Traffic, an international organisation fighting against the trafficking of fauna and flora, affirms the fact that in the DRC, “there is no national system for managing ivory stocks”.

Instead, the ivory is dispersed within several state structures, including the Central Bank of Congo, the patrol posts of the ICCN, the General Directorate of Customs and Excise, the courts and tribunals, police stations, and provincial or local environmental services. This decentralisation predisposes the ivory to theft and corruption, because each service involved in a seizure can keep the ivory or cash for an unlimited period.

In 2022, CITES DRC released a progress report on the implementation of its National Ivory Action Plan, stating that DRC was “on track” in regards to “inventorying existing ivory stocks and developing, at the national level, a reliable system for the storage and management of confiscated ivory”. But it provided no other details on this progress.

Two years after the publication of the Traffic report, there is still no centralised storage mechanism in the DRC for illegal wildlife products.

Silent laws

The DRC’s national legal and regulatory framework does not address the management of ivory stocks. But, in practice, protected wildlife commodities such as ivory that are seized or found on the carcasses of dead elephants or on the ground are entrusted to the ICCN.

“This institution stores it in its offices and/or sites while waiting to consign them to the Mint of the Central Bank of Congo, which would hold fairly large stocks of ivory,” according to the Traffic report. “Other ivory is stored in the prosecutors’ offices, customs warehouses, provincial environmental coordination offices, or even in the stations of the various protected areas (products seized by guards during anti-poaching patrols) of the ICCN. The stocks held are not inventoried and no exact figure has, to date, been given or the way in which they are kept.”

The 2014 Congolese law relating to the conservation of nature provides in its article 83 that “the specimens and products, as well as the objects used in the commission of offences against this law, are confiscated and entrusted to the public body responsible for conservation”.

But the law did not clearly mention the specific body that should ensure the custody of the seized objects. In article 36, instead, the law mandated that “the province sets up a public body whose mission is to manage protected areas of provincial and local interest. A decree deliberated in the Council of Ministers or an order of the provincial governor, as the case may be, fixes the status.”

The name of the Congolese Institute for the Conservation of Nature, which was created in 1975 and modified in 2010, does not appear in this law as the body responsible for storing seized objects, although the ICCN’s establishment was prior to the passing of the wildlife law.

In addition, the law provides for the establishment of similar bodies at the provincial level for the management of protected areas of provincial and local interest. This suggests that the legislation was planning for the establishment of new future bodies to manage wildlife items.

Judicial system

“When it comes to biodiversity, it is often very difficult, in a corrupt judicial system, to bring evidence before a judge,” said Olivier Ndoole, who has worked as an environmental and land lawyer in the DRC for 10 years.

“Currently, with corruption, we happen to contribute to the arrests of poachers with elephant meat for example, but tomorrow before the judge, this meat or the remains will be declared as belonging to a goat. These are cases that we have encountered.

“It is the same for the flora. An individual can be arrested making embers in the park or in a protected area. But, in court, we have to prove the difference between the embers that come from the park and those from elsewhere to really prove that they come from the park,” he said.

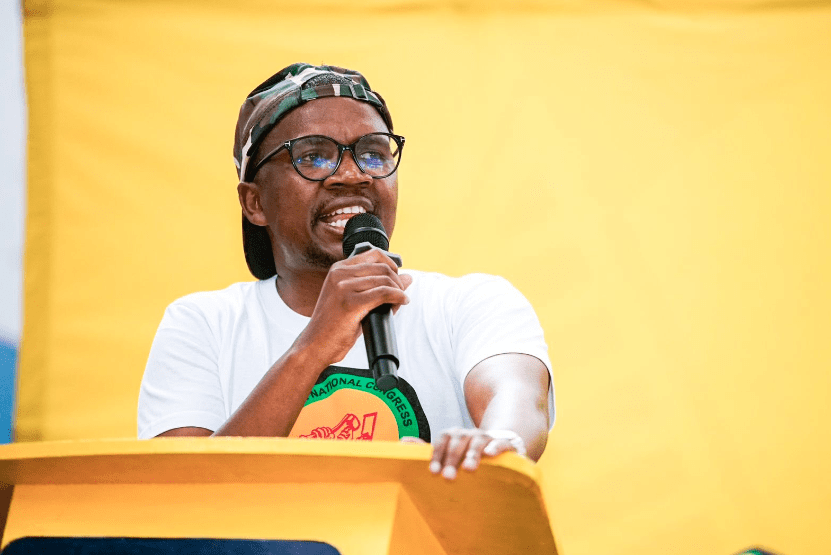

This view is supported by wildlife activist Adams Cassinga, who founded Conserv Congo, a local conservation NGO. Using a network of about 100 focal points (agents) across the DRC, Conserv Congo carries out investigations into crimes against fauna and flora in the Congo Basin.

“In fact, it is a phenomenon that we have never understood. And, it gets tough when there’s a dark hand behind it,” Cassinga said. He added that he has examples, but won’t go public due to fear for his safety.

The fight for conservation also comes up against influence peddling — the use of position in exchange for money or favours — which is common in the DRC, Cassinga said. “The people who are supposed to know and contribute to the protection of wild species, in reality they don’t know.

“This ignorance is even rooted in our leaders, who are supposed to tell us what to do about it. All because conservation, like the rest of the sectors in the DRC, is always politicised,” Cassinga added.

According to him, in the DRC sectors that should be managed by scientists or technicians, such as the conservation of fauna and flora, are prejudiced by the interference of politicians. This makes it difficult to fight wildlife crime and wildlife trafficking.

Data quest

For five months during the course of our #WildEye Eastern Africa investigation, we attempted to acquire data on court cases of wildlife crime in DRC from various authorities, including police, courts, customs services, airports, ICCN and CITES DRC, to no avail. This quest included multiple meetings with the managers of these services and their communication officers, where unfulfilled promises were made to share the information.

For the provinces of North Kivu and Ituri, where a state of siege has been in place since May 2021, all cases under investigation by the civil courts have been transferred to the criminal courts. The latter were overwhelmed by piles of files to process, which meant that our requests fell on deaf ears. This despite the passing in March 2023 of a new law in the DRC on the exercise of freedom of the press. In its article 96, this law obliges any holder of information of public interest to make it available to media professionals.

The #WildEye Eastern Africa map by Oxpeckers Investigative Environmental Journalism in partnership with InfoNile tracked 134 cases of wildlife crime in the DRC between 2017 and 2023. But most cases stopped at arrests and did not document the status of court cases and convictions. Many traffickers of illegal wildlife were arrested as they were en route to Uganda through eastern DRC cities and towns, including Butembo, Beni, Goma, Bukavu, and Garamba National Park on the border of South Sudan.

Regular audits

According to Traffic, it is necessary to define a national management system for elephant ivory stocks for the DRC, taking into account the various sources of ivory, the services competent to collect them, the measurements and marking, recording, storage and securing of stocks, and tools and means for good management. The system should also include regular audits.

The same is true for other wild species, for which reserves must be created, according to the NGO. In addition, there is a need to strengthen the security of existing reserves. For example, the headquarters of Virunga National Park in Rumangabo houses the Senkwekwe Centre, the only facility in the world for orphaned mountain gorillas. Each of these orphans has lost its family as a result of poaching. They are now cared for by expert staff who provide daily care.

As far as policies are concerned, in 2015 the DRC developed the National Ivory Action Plan. Its overall objective is to “strengthen the fight against elephant poaching and illicit trafficking in ivory and other elephant specimens in collaboration with all relevant actors”. This plan revolves around seven specific objectives, including that of “improving the system of management and traceability of ivory stock in the DRC. If this plan is implemented, positive progress can be made in the future.”

Community integration

For Adams Cassinga, awareness must be raised to educate the entire Congolese community about the endemic species that the country abounds in and the need to protect them. He proposes drawing inspiration from Kenya and other countries in Southern Africa which, instead of keeping ivory without any assurance of protecting it, incinerates it. This will prevent it from falling back into the illegal circuit, he said.

For his part, Olivier Ndoole believes that it is necessary to restore the authority of the state, not only in protected areas, but also throughout the national territory. According to him, the black economy of illicit trafficking around Virunga feeds armed groups who promote poaching, cutting wood for embers and fishing illegally on Lake Edward.

Ndoole also encourages education of local communities to help them become “intelligence agents” in the fight against crime around fauna and flora.

To fight against poaching and wildlife trafficking, Conserv Congo has already initiated several community projects in livestock and agroforestry. They are found in the Bateke plateau on the outskirts of Kinshasa, in Mokoto in the province of Tshuapa, and in Ikoma in the province of South Kivu. Here, Conserv Congo supports the local communities to practise livestock farming and agroforestry to give them alternative livelihoods instead of poaching and contribute to the preservation of forests and food security in households.

“The objective is to dissuade those who can go into the forest to become a poacher to choose breeding. But also, people in rural areas live only on bushmeat. If someone tells you that they ate meat, you must immediately think of bushmeat. Thus, we allow them to have access to meat near their homes with the aim of contributing to food security,” said Cassinga.

Conserv Congo plans to set up a similar initiative soon in Sake near Virunga National Park in North Kivu province.

Former poacher

As part of this investigation, we collected the testimony of a former poacher who now works as a journalist at a community radio station broadcasting from Kyavinyonge, a fishery on Lake Edward located in Beni territory in the province of North Kivu, in the heart of Virunga Park.

He said poaching is often considered the main source of income for the poacher, with the meat intended both for sale and home consumption. He only abandoned the practice after becoming aware of the dangers involved in poaching. This awareness has now been reinforced by recognising the need to conserve wild species for the good of the whole community.

“In radio broadcasts as well as in public speaking forums organised here at home by the partner organisations of Virunga Park, I have been made to understand that if I kill a hippopotamus, I contribute to lake infertility, on whom several families in my locality depend. I also understood that tourism can generate a lot of jobs here at home, if we do not kill the species that are in the park,” he confided.

This former poacher insisted on the urgency of giving jobs to the inhabitants around the protected areas to dissuade them from violating the parks and getting involved in the illicit trafficking of ivory and wild species.

Today, with his microphone and through the Kinande language mainly spoken in the region, he sensitises his community and raises awareness to lead the protection of fauna and flora, for his own good and that of all humanity.

This story was supported by InfoNile, in collaboration with the Oxpeckers #WildEye Eastern Africa project, with funding from Earth Journalism Network’s Biodiversity Media Initiative project

Wildlife protection activist Adams Cassinga holds the skull of a buffalo, indicating the existence of this species in the past in the Bombo Lumene protected area near Kinshasa © Conserv Congo

Discussion about this post