A new interpretation of an ancient inscription on a Swedish ring reveals insights into how Vikings handled money and debts. The inscription on the Forsa Ring–or Forsaringen in Swedish–details some of the hefty sums that were part of the Viking economy and is the oldest known legal text in Scandinavia. The new analysis is described in a study recently published in the Scandinavian Economic History Review.

What is the Forsa Ring?

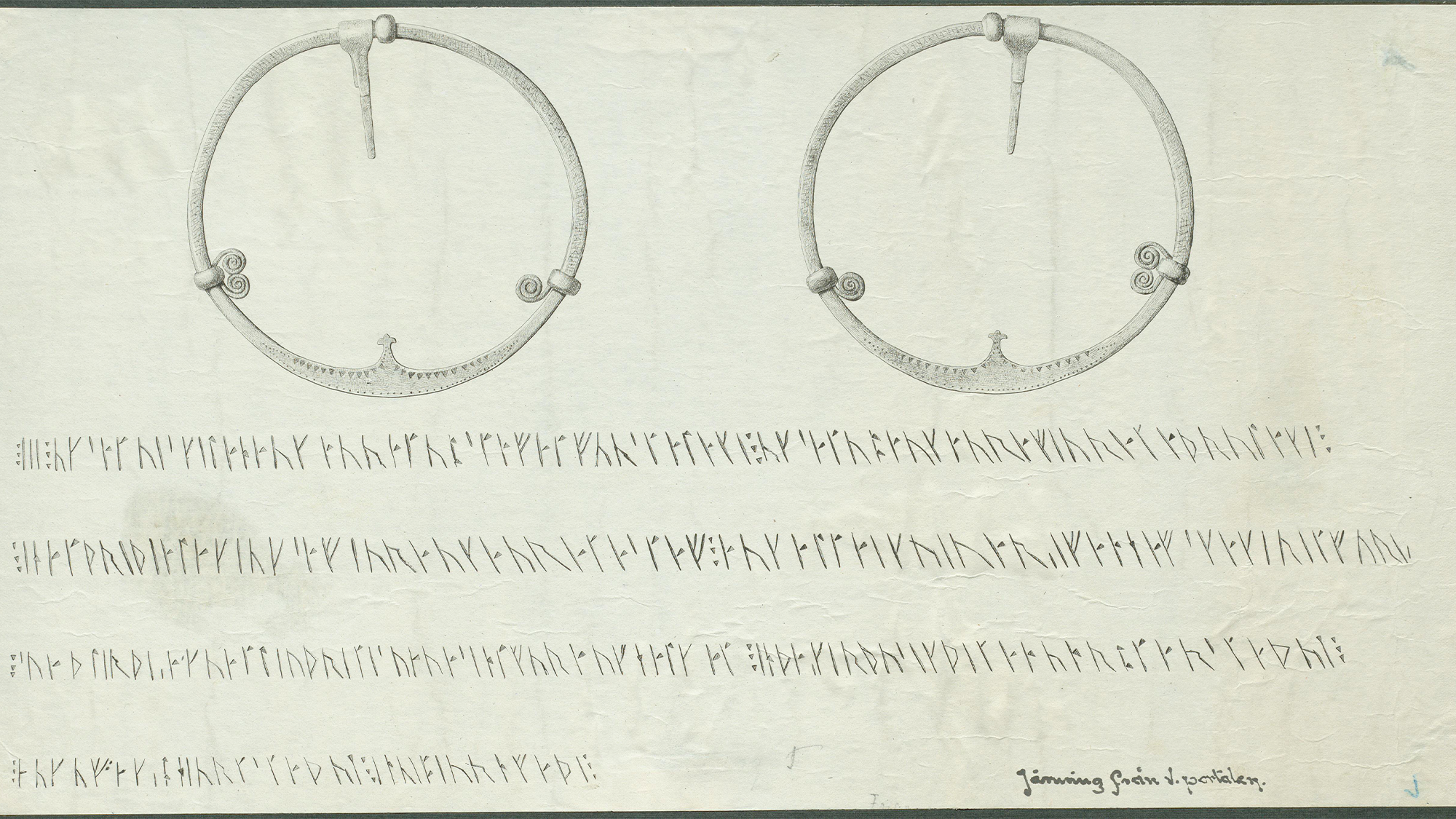

The Forsa Ring is a 16-inch-wide iron ring that was discovered in Hälsingland, Sweden. It comes from the 9th or 10th century CE, and is believed to have been the door handle of a church in Hälsingland. Oath rings like these were common in both Viking and Anglo-Saxon circles.

[Related: Some modern-day Scandinavians lack the ancestral diversity of Vikings.]

The inscription on the ring contains almost 250 runes, or letters in the alphabet used by the Vikings and other Germanic peoples. The inscription itself describes how the Vikings would have handled monetary fines in a flexible and practical manner.

“The Forsaringen inscription uksa … auk aura tua was previously interpreted to mean that fines had to be paid with both an ox and two öre of silver,” study co-author and Stockholm University economic historian Rodney Edvinsson said in a statement. “This would imply that the guilty party had to pay with two different types of goods, which would have been both impractical and time-consuming.”

The new translation

In modern English, the new translation of the Forsa Ring is:

One ox and [also/or] two öre of silver to the staff for the restoration of a sanctuary in a valid state for the first time; two oxen and [also/or] four öre of silver for the second time; but for the third time four oxen and eight öre of silver.

By re-examining the translation of the word auk from the previous interpretation, the meaning changes so that fines could be paid with either one ox or with two öre of silver. An öre was roughly 25 grams of silver.

“This indicates a much more flexible system, where both oxen and silver could be used as units of payment,” said Edvinsson. “If a person had easier access to oxen than to silver, they could pay their fines with an ox. Conversely, if someone had silver but no oxen, they could pay with two öre of silver.”

This system meant that multiple forms of payments could be used at the same time, reducing transaction complexity and making it easier for people to pay. The new interpretation also aligns better with how the system functioned later on under regional laws.

“As an economic historian, I particularly look for historical data to be economically logical, that is, to fit into other contemporary or historical economic systems. The valuation of an ox at two öre, or 50 grams of silver, in 10th-century Sweden resembles contemporary valuations in other parts of Europe, indicating a high degree of integration and exchange between different economies,” said Edvinsson.

Viking economics

During the Viking Age, an ox would cost 2 öre of silver or 50 grams of silver. This corresponds to roughly 100,000 Swedish kronor or $9,610 today. When compared to the value of an hour’s work, the fine on the Forsa ring was pretty steep.

[Related: Horned helmets came from Bronze Age artists, not Vikings.]

One öre was likely the same as nine Arabic dirhams, a currency that was widely circulated among the Vikings. A common price for a slave or servant–known as a thrall–was 12 öre of silver, or approximately 600,000 Swedish kronor ($57,653). By comparison, if a free man committed murder, the fine paid to the murder victim’s family to avoid further bloodshed–a wergild–was much higher at about 5 kilos of silver. This is about 10 million Swedish kronor or $960,000.

The major difference in value between a thrall and a free man reflects the power dynamics in a slave society.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d1/82/d18228f6-d319-4525-bb18-78b829f0791f/mammalevolution_web.jpg)

Discussion about this post