Happy 20th anniversary, Facebook – now please explain what the hell is going on.

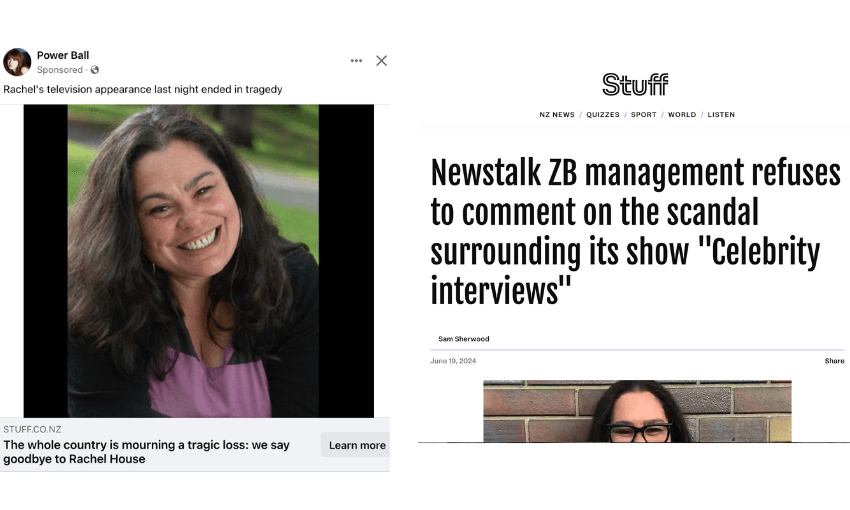

According to Facebook, Rachel House is dead, Daniel Radcliffe is starring in a new Harry Potter film, and a woman with nipples for knees is the dream girl some men desire.

None of these things are true or real.

Click the link on a recent post in my newsfeed about the whole country mourning a tragic loss and saying goodbye to Rachel House, and you’ll find a pretty good spoof of the Stuff website with a completely made-up story about Newstalk ZB and a celebrity scandal “written” by Sam Sherwood. Sherwood is a real senior journalist at Stuff reporting on crime. He did not write this story.

It’s from a family of scams known as FizzCore or Celebcore, and they are rampant on Facebook. Other well-known New Zealanders who’ve apparently ruined their lives and shocked the nation recently include Hayley Holt, Jenny-May Clarkson and Clarke Gayford. In response to the scam using sensationalist headlines about Gayford, Meta (Facebook’s parent company) told the Herald it had removed the ads and that the company had removed 631 million fake accounts globally in the first quarter of 2024 alone.

These scams make money for Facebook as the posts appear in our feed because the scammers, squatting on dormant, hijacked or fake Facebook profiles and pages, pay to get the posts in front of us. Search out the original “Power Ball” page running the Rachel House post, and you’ll find it’s pivoted to running fake videos of a fake Elon Musk shilling a fake investment scheme.

All traces of the House scam post are gone in Facebook’s ad library. Only god knows why, but a search of “Power Ball” pulled up an avalanche of ads that may or may not be run by bot farm of erotic literature fans. Like a hydra, you cut off one head, and two more ads about witnessing your brother’s best friend masturbating appear.

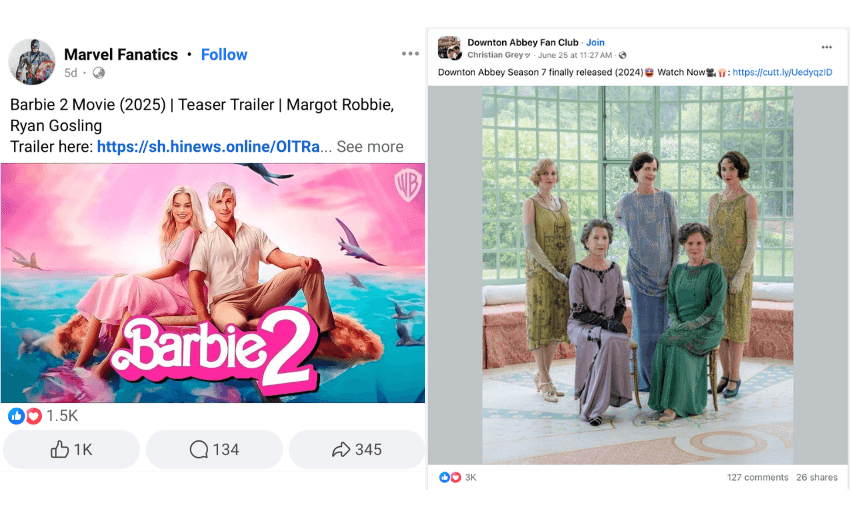

The Radcliffe Potter film post, featuring a fake image of Radcliffe inexplicably cosplaying as Russell Crowe in The Insider, is one of many about that franchise and belongs to another rampant genre of fake news on Facebook that farms engagement in the fertile lands of film and television fandoms. Variations of the fake Potter film posts are easily found through searching – some feature fake trailers, others are just bad AI art and some link off to hour-long videos of what looks like a Microsoft Windows screen saver with a promise that if you click a link, you’ll be able to watch this completely fake movie.

Post after post about fake sequels to popular shows and movies are pumped out via pages called “Netflix Community”, “Marvel Fanatics”, or “Downtown Abbey Lovers”. According to these pages, a second season of The Queen’s Gambit and a seventh season of Downtown Abbey is coming, and Barbie 2 already has a trailer. There is nothing to confirm these claims from reputable sources, but real people in their tens if not hundreds of thousands interact with these posts and get really excited.

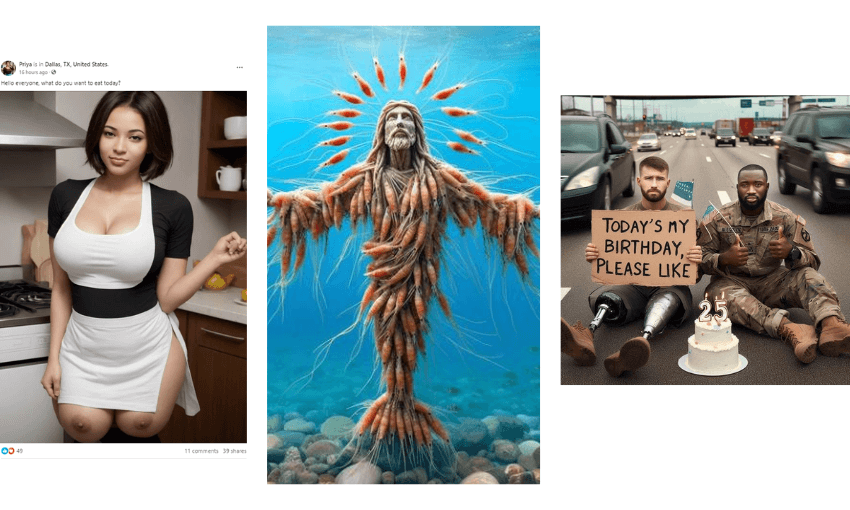

The dream woman, ol’ nips for knees (kneeps? knits? knoobs?), is perhaps the most alarming to look at, but her kind – the AI-generated woman – is everywhere on the platform whose stated mission is “to give people the power to build community and bring the world closer together.”

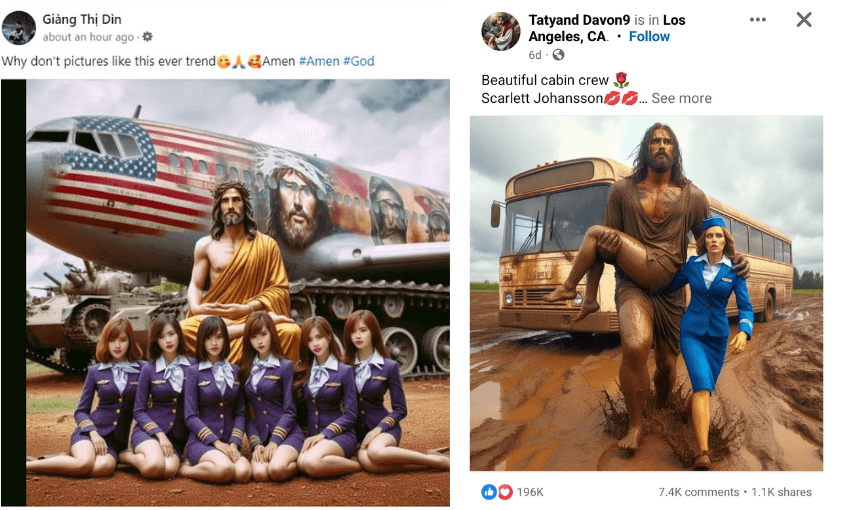

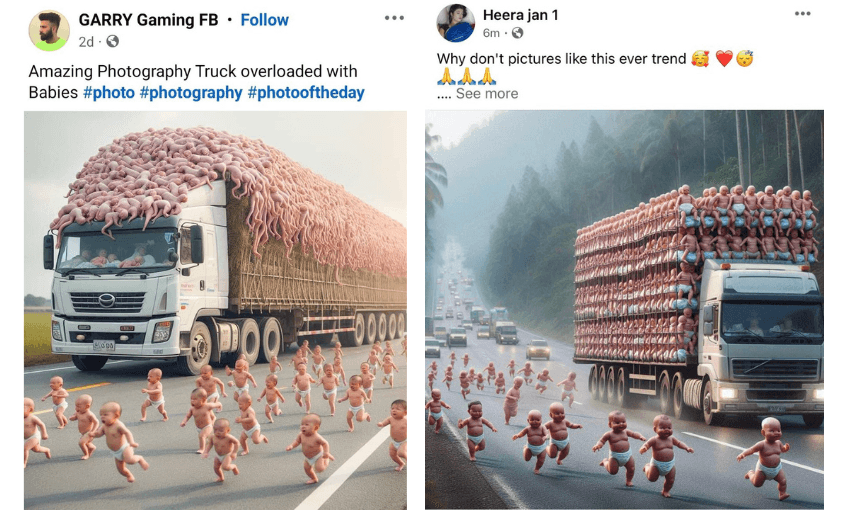

If community building, people power and closeness come from bonding over an infinite number of AI-generated images of airline hostesses posing with Jesus, soft porn versions of women in the army, legless soldiers and trucks full of babies, then Facebook is on track. If the company has something more authentic and human in mind, it’s failing miserably.

The proliferation of pages dedicated to pumping out AI “art”, or “slop” as it’s been named, has been increasing for a while. 404 media began tracking it in December last year. Shrimp Jesus broke through into mainstream reporting in March and April. One of the most popular genres is airline stewardesses posing with Jesus. Something about the soft-porn aesthetic, women in service roles and religion really pushes engagement buttons. Some of these pages, like “Beautiful Cabin Crew“, have hundreds of thousands of fans; again, real people interact with them. They are very likely zombie pages or fake profiles, run by bots, fuelled by an unending stream of posts featuring AI imagery and the same repetitive words:

“Why don’t pictures like this trend?”

“Close your eyes 85% to see magic”

“Beautiful cabin crew Scarlett Johansson”

“You will never regret liking this photo”

“99 years of luck and you will never lack money for your trip and travels”

“Today is my birthday I just want a wish”

A lot of the slop is surreal, grotesque, amusing, disturbing, and obviously generated by AI. Other pages, named benign things like “Creative Gardens”, “Gardening Tips”, “Floral Serenity”, Garden Decorations, “Melissa’s Recipes”, and “Mountain Cabins”, focused on gardening, recipes, travel photos or luxury holiday destinations, post less overtly bizarre imagery but are still prolifically pumping out posts using AI-generated images of giant hydrangeas or idyllic cabins in the mountains. Tracking, following and curating the growth of slop is now part of our internet culture, with Twitter accounts like Insane Facebook AI Slop and Facebook groups like Ai Boomertrap pulling decent followings.

Garage Day’s Ryan Broderick has spent some time trying to figure out the answer to the question I imagine many have by now—what are these AI “art” pages doing and why? No one really knows. Broderick, a seasoned pro of writing about and examining internet culture, couldn’t quite put his finger on the end goal of these pages. Researchers at Georgetown and Stanford universities were equally stumped. It may be that these pages are just farming engagement and will be sold on, or they’re priming people for scams. Perhaps there isn’t a point.

Facebook launched twenty years ago as The Facebook and was initially open to Harvard students and then students across the US. By 2006, anyone in the world over the age of 13 could have an account. Parent company Meta swallowed Instagram in 2012 and acquired WhatsApp in 2014.

In October last year, Facebook ranked as the third-most visited website in the world, and it is still the largest social media platform in the world. In New Zealand, it has around three million users. Across all age demographics, the majority of us are using it at least once a week. Facebook NZ paid out $157.4m to its subsidiary in Ireland for the 12 months ending December 21 2023. It booked an after-tax income of $3.1m here for the same period. It has scale like no other platform and remains wildly attractive to advertisers for that reason.

Despite its dominance, we seem to worry less about what’s going on on Facebook than newer social media platforms. Facebook has lost a lot of cultural cachet. Its users have aged up. It isn’t cool and hasn’t been for a long time. Facebook is seldom cited as the source of the latest meme or internet trend. Once the remnants of the Cambridge Analytica scandal faded, internet culture and tech commentators largely moved onto legitimate concerns and moral panic about generative AI and vertical video platforms like TikTok and Instagram.

In the scheme of technological innovation, the platform’s mechanics as we humans use it, and its revenue model, derived from delivering targeted eyeballs to ads, are quite primitive and haven’t radically changed since the introduction of the newsfeed in 2006. There have been multiple redesigns and additions, like Groups, Pages, and Marketplace. Instant messaging was split out into a different app called Messenger in 2014. Ultimately, however, people, businesses, organisations, and now a galaxy of bots post words, images, or videos, and other people and now a galaxy of bots respond by “engaging” with a like, share or comment.

What has changed and what feels far more otherworldly and inhuman is the force driving what we see in our newsfeed. Controlled by an algorithm that is utterly opaque and dominated by either advertising or content the algorithm deems engaging, the number of recommended posts in your newsfeed (posts from pages, groups or people you don’t follow) has doubled since 2022. According to the researchers, Facebook is also actively recommending AI content, or slop, into users’ feeds.

We might laugh at it, but groups like Ai Boomertrap are named deliberately in honour of those deemed most likely to be susceptible to believing in the veracity of the images. We have spent a lot of time (correctly) worrying about the impact of Meta-owned Instagram on young people, and perhaps not enough worrying about its older sibling and its impact on our parents and grandparents.

Ten years ago, halfway through Facebook’s current lifecycle, I was 34 and using Facebook as I imagine most people did. I posted photos, kept friends and family updated on my life, and commented on other people’s posts. I made promises to catch up. I was being invited to events and diligently filing my RSVPs. It was a small world within a vast galaxy filled with the familiar and the utility offered by a platform that largely functioned as a digital extension of my real-life social network.

All that utility and connection is gone for me. My use of Facebook these days is passive. I use it to look at pictures of my dogs at daycare and for researching pieces like this. I rarely see anything from friends and family. I don’t know if this is because no one I know really posts anymore or because Facebook has stopped showing it to me. I certainly never see anything from the real pages I follow. Despite visiting the dog’s daycare’s Facebook page at least twice a week, their posts never appear in my newsfeed. Where we were once told that the things we engaged with then drove the algorithmic decisions about what we continued to see in our newsfeeds, it now seems like you see whatever Facebook wants you to see. It feels increasingly random, wild and beyond the realms of relevance or use.

My newsfeed these days largely consists of three things: posts from the groups I’m in, ads, and now, the plague-like sprawl of fake posts, bot-farmed engagement and meaningless imagery.

Facebook groups can be fun, funny and useful. They’re also quite unregulated arenas for a form of neighbourhood watch that can border on surveillance and vigilantism. Like any social media platform, they reward outrage and anger. They breed a kind of pseudo connection where real world acts of neighbourly behaviour or kindness can be substituted for a like or comment. It’s very likely, however, that are now the most people-powered aspect of Facebook.

The ads we see are the price we pay for not paying any price to be on Facebook. If you are not paying for the product, you are the product. Facebook’s lucrative advertising business sits flush alongside its transformation from a digital hub of genuine social interaction to a chaotic landfill of misinformation and AI-generated freak shows. Sometimes I wonder if the clothing brands targeting me there know that images of their meticulously crafted garments that whisper “quiet luxury” are hanging sandwiched between the visual scream-fest that is the AI-generated imagery of a woman with tits for knees and another post about another New Zealand celebrity who has fake died.

Because I worked in social media for so long, during its halcyon days as a marketing panacea for all businesses, I have developed a tragic habit. Whenever I see a local business advertising its Facebook page on the side or back of its vans or vehicles, I look it up. There is a graveyard of pages belonging to plumbers, local petrol stations, and businesses that should never have been on Facebook in the first place because they never had the raw ingredients but were all rabidly encouraged to follow the trend.

There are still people grafting away with pages of 450 fans, trying desperately to wring out what’s left of organic reach or the promise of community building, but many have given up. Many are now remnants of a Facebook that promised a lot and no longer delivers. Space junk floating among all the other junk. If we were sold Facebook as a means of staying connected and now feel duped, a number was also done on many small businesses.

There are still plenty of brands and businesses using Facebook well and productively. Many of them have either invested in turning themselves into the right-shaped balloon animal to please the algorithm, spend money on ads, or, because of what they do, fit more naturally into an environment where people want to be entertained or influenced. Commercial radio stations do a great job on Facebook, but they’re also a prime example of a business that has the raw ingredients to make it work. They have personalities people want to follow, have jumped on video quickly, and content is primarily light and topical.

In the media and journalism business, conversations about its well-documented troubles often call for it to innovate in the face of disruption from global tech giants like Meta. Sometimes, the implication seems to be that these companies provide a blueprint for innovation. If Facebook is the blueprint in its current state, then that implication is illogical, dangerous and unfair. Social media platforms like Facebook can operate at their highly desirable scale by leveraging unmoderated user-generated content and, increasingly, vast amounts of fake news and AI-generated imagery to drive engagement. Their business models thrive on maximising interaction and data collection and prioritising viral content regardless of its accuracy or origin.

Based on what I’ve seen on Facebook lately, is this really what we want to see our media companies doing? I could, hypothetically and with a skills upgrade, multiply The Spinoff’s output and reach by a thousand if I gave over our editorial and advertising standards to pumping unending amounts of shit into an already polluted river. We could be huge if only we removed our guard rails, humanity and insistence on quality. Instead, we maintain a commitment to those things and are continuously raked over the coals for not being enough like the companies where playing the quantity game to achieve scale and harvest data has far outrun any focus on quality.

Right now, there’s a live conversation about the likelihood of Meta pulling news from newsfeeds in New Zealand as a result of the Fair Digital News Bargaining Bill and the government’s move to force international tech giants to do deals with local news media or submit to binding arbitration. Meta has done exactly that in Canada and may follow suit in Australia, where similar legislation exists. It makes you wonder what, of any quality or utility, will be left in our newsfeeds if friends, family, and news are largely gone, and AI slop and fake news continue to proliferate.

Everyone’s Facebook newsfeed is different — there is no singular Facebook; instead, there are billions of algorithmically determined Facebooks. Maybe yours is fine, maybe you still see news and friends and family, and your feed looks like mine did in 2014, just with twice the number of posts you didn’t ask for. My algorithm is undoubtedly borked by my sick professional interest in the weirder aspects of the platform.

Despite that granularity of experience, there is a growing consensus that Facebook is something of a wasteland, a beast that has grown billions of limbs that, at various points, have turned gangrenous, dropped off, and now haphazardly fly around hitting you in the face when you visit. As 404 Media’s Jason Koebler told The Guardian recently, the proliferation of AI “art” is representative of the “zombie internet” where Facebook is now “a mix of bots, humans and accounts that were once humans but aren’t any more mix together to form a disastrous website where there is little social connection at all.” The scale of junk cluttering the place seems like it can’t be thwarted or reigned in and is now beyond cleaning up, control or regulation.

I used to worry about what would happen to my social media profiles when I died. I didn’t want them hacked or taken over, freaking out those left behind. I don’t worry about that happening with my Facebook profile anymore. A hacked AI me posting from beyond the grave seems kinda chill compared to the things I’ve seen.

Who knows who will be dead, according to Facebook, next week? At least we can take comfort in knowing someone will make a trailer for a third Barbie movie, and an army of AI-generated soft-porn soldiers stand at the ready to shepherd the nation through its mourning.

Discussion about this post