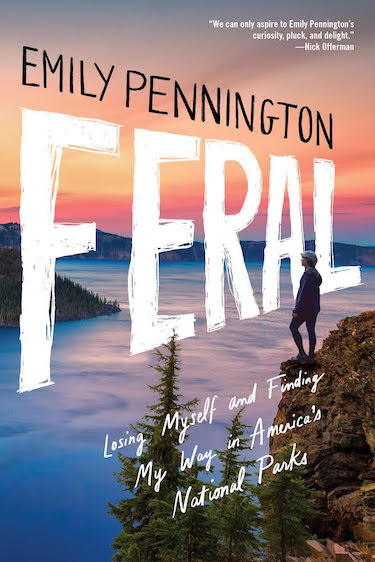

A few years back, Emily Pennington pitched us an idea: What if I travel to every single national park in the US and write about it for AJ? We loved the idea, but unfortunately didn’t have the budget to commit to dozens of stories at once. Thankfully, she did the trip anyway and took great notes. The result, besides a lifetime of memories, is Feral: Losing Myself and Finding My Way in America’s National Parks.

Pennington sent us the following excerpt to publish in full, and a copy of the book. It’s great, I’ve enjoyed it thoroughly. A link to get your on copy is below. – Ed.

***

There’s a raccoon on my goddamn pillow.

I could see my breath illuminated by the van’s headlights in the inky black of night as I stooped over a wooden picnic table, guarding my bounty. Compared to the wilderness that surrounded me—moss-laden trees, crags, creeks choked with poison oak—my small stove and LED lights must have seemed like the apex of high society to the forest’s locals. It’s no wonder I had uninvited dinner guests.

Still, I screamed. My heart leaped into my throat, and I lurched toward the unattended vehicle with the confidence of an unruly toddler, howling a convincing, “No! Bad raccoon! Go away!” As if the greedy little trash panda understood English.

He ran up a nearby tree as I slammed the sliding door shut and returned to my frying pan, only to find a second pair of beady eyes, hungry and expectant, staring back at me from the opposite end of the table. Killing the flame, I nixed my plans for eating under the stars and sulked as I shoved a tortilla into my mouth from the driver’s-side seat.

The closest free campsite I could find that night was an hour’s drive away. I set off in the darkness on a winding road through cow pastures and dilapidated ranch houses. A white pickup truck roared past me, headlights blazing a blinding white swath through the trees. Am I about to be assaulted by Proud Boys drinking Miller Lite? Mary’s words of warning were pinging around in my brain. I refocused and parked near a placard marking site number two, frost already clinging to the surrounding shrubs. Lying in bed, I gazed up at the fabric-covered ceiling my friend Jack and I had glued together two years prior. There was the sparkling quilt embroidered in emerald green that I’d swooned over on a trip to India many years ago, sensing that it possessed good magic and would someday occupy an important place in my life.

But now, as I tossed and turned alone and the temperature dropped, the pull of my nerves and my fear of unknown creatures lurking just outside the van door clobbered any goodwill the tapestry offered. I couldn’t help it. I hurtled a second arrow directly into my chest. The fact that I didn’t have cell service only worsened my state. Every little sound pricked me awake. Every new thought was a hellion pummeling my sense of safety.

Someone will wake me in the night with a shotgun. I am going to be followed by the truck people and murdered and raped. I will be kidnapped and taken to a place where bears will eat me and hillbillies will tap-dance on my grave. This is stupid. Thisisstupid. Thisisstupid.

I rummaged through my first-aid stash, took half a Xanax, and passed out.

Morning came, and the world was awash in color. Tiny frost crystals sparkled on the oak trees that surrounded my campsite, and I lingered in bed, eating oatmeal and drinking coffee, waiting for the road to thaw. It seemed ridiculous that I had been so afraid of this hillside campground only hours before; everything was so beautiful, soaked in yellow light. If I was to survive a year in the wilderness, it seemed, I would need to accept that each day had two radically different sides: a light-filled expanse in which anything was possible and a frigid waiting game of darkness and slumber.

It wasn’t personal; it just was. Only specialized animals were nocturnal, and I, sadly, was not one of them. I vowed to let myself do whatever was necessary to stay calm and get a good night’s sleep as the year progressed. If that meant skipping a sunset to find a safe campsite, so be it.

When I felt ready to drive, I cruised down the mountain road blaring Simon & Garfunkel, feeling grateful that the evening’s sinister vibe had all been in my head. I am in fabulous central California! In the winter! And it’s sunny!

After parking the van in a small lot at Old Pinnacles Trailhead, I felt eager to hear the familiar crunch of my boots against the earth, the clack-clack-clacking of my trekking poles like a heartbeat that could bring equilibrium to my own. I filled my backpack with crackers, cheese, and protein bars, forgot my sunscreen, ran back to the van to grab my sunscreen, and started walking. The plan was to link up the High Peaks Trail, the Steep and Narrow section, the Rim Trail to Bear Gulch Reservoir, Bear Gulch Cave, and Moses Spring, capping it off with a little hike along Chalone Creek. An all-day romp around the entirety of the park.

Quail scuttled across the trail as unseen warblers called out from bush to bush along the fifteen-hundred-foot ascent that marked the beginning of my day. In all my years of tramping around Southern California, I had never noticed such a variety of birds on a single hike before. They fluttered around the low-lying chaparral, belting out their high-pitched trills as I walked. By the time I got to the higher-altitude Steep and Narrow area, I was sporting a massive grin.

I ascended dozens of near-vertical stone steps that had been cut into the massive rock formations by 1930s trail crews. These park improvements, a product of Roosevelt’s New Deal, are everywhere, if one knows where to look, and stumbling upon them was a fun Easter egg in any park visit.

I switchbacked down, down, down toward Bear Gulch Cave, kicking dust off my shoes as I practically galloped downhill and entered the eerie, boulder-strewn tunnels. Due to hibernating bats, much of the cave had been closed off, so I left as soon as I arrived and kept on walking.

I have a poet friend who says that, for him, woodpeckers symbolize love. I’ve never quite understood why, but whenever he hears one on a trail, he won’t give up until he’s located and identified it. Is it a pileated or a ladder-backed? He is relentless in his search for this kind of reverent affirmation in the wild. I’ve watched this forty-five-year-old man leap over downed trees and push through blackberry bushes to get to a small red-and-black bird and exclaim, “Ah, ladder-backed!” with a grin on his face that could swallow an ocean.

So it was with enormous glee that I rounded a corner near the Bear Gulch Nature Center to find not one but five acorn woodpeckers hopping across the tree bark in search of a meal. My mouth pulled into a toothy, childlike grin as I watched them scamper about from oak to oak. I felt like the universe was winking at me after my uneasy night spent solo. Feet on earth, I practically flew down the last few miles of the trail, my gravity and mood restored. Maybe this kind of careful attention was what I needed to recognize my place in all things. Maybe alone wasn’t so lonely after all.

But I had a date with my partner, Adam, for park number three, Death Valley. I made it back through my planned loop hike and hopped into Gizmo to speed off across the pastoral hillsides, shaking the balmy late-afternoon heat from my skin. Despite my solo revelation, I was ready for company.

The next morning I woke with a horrific head cold, my skull an overripe melon of snot. Tossing and turning with a balletic grace so as not to wake my slumbering boyfriend, I had slept maybe four hours in total. I felt entombed in my own body, pressure building like an underwater balloon. And yet, there was a schedule to keep. The tiny dictator living inside my mind knew that parks still needed to be seen.

“Adam . . . I feel like ass. Can you help pack up the van?”

Adam playfully smacked my butt as he rose out of bed, donning a pair of jet-black hiking pants, a periwinkle T-shirt, and a fuzzy blue Patagonia jacket that made him look like Cookie Monster on a diet. Say what you will about his fashion sense, but the man’s immune system was rock solid. Over a year and a half of dating, I had caught nearly every illness known to humankind, including an ear infection, a stomach bug in Nepal, and a particularly attractive stretch of two colds and a flu in under eight weeks. Adam, on the other hand, threw up once in Arizona. If staying peaceful and well under stressful conditions were a horse race, my odds would be on him.

A full ten years older than I was, Adam was quieter and better versed in his mindfulness practice, remaining calm and centered in the face of the busy modern world. He had the uncanny ability to shake off a migraine; show up to his day job at a virtual reality company; complete a series of repetitive, mind-numbing computer tasks for eight hours; sit through traffic; and still manage to cook dinner for us before collapsing onto the couch to watch TV.

I was more the fun-loving, type A extrovert with a big heart and bigger dreams, who mapped out all of our adventures while working as an executive assistant and moonlighting as a wannabe writer.

Regardless of our outward personality differences, Adam was always down for any shenanigans I proposed, whether it be a 17,769-foot walking pass on the Annapurna Circuit; an overnight backpacking trek to a series of muddy, secluded hot springs in the Sierra Nevada; or saying “I love you” for the first time in the belly of a mosh pit. He wasn’t as wilderness savvy as I was, but it didn’t matter. Whenever I got a hankering to escape Los Angeles, I planned and Adam followed.

We sped across Highway 395, the relentlessly cheerful timbre of Jonathan Van Ness’s audiobook, Over the Top, serenading us as our churning tires spun toward the Panamint Mountain Range. Chaparral and the occasional alpine conifer gave way to a barren expanse of huge berms speckled with the occasional cactus or creosote bush. Because I’m a devotee of lush mountainside forests, the desert has always struck me as inherently lonely.

Its rows upon rows of mountains, in which nothing appears to live, leave uneasy pangs in my stomach. As we veered into the western entrance of the park, the waste only intensified. Death Valley is an arid wonderland, as if the god of rocks got bored one day and frivolously slammed together seemingly contradictory geology, neglecting to add the ingredients for organic life. Coarse rhyolitic lava flows hugged granitic intrusions. To my left were a series of enormous sand dunes. To my right, the turnoff for Mosaic Canyon. Van Ness’s effervescent tone made me giggle through my sneezes as Adam steered the van toward the latter.

Desolation and fabulous queens. I couldn’t think of a more polar-opposite pairing.

Parked and suited up in our outdoor uniforms of backpacks, boots, and trekking poles, the two of us set off on a gravel path toward the canyon’s gaping mouth. Once we were inside, the light began to shift into extravagant honeys and buttermilks. The walls narrowed, and I traced my hands across cool, flash flood–polished marble and the rougher, more colorful breccia that lay just beyond. This mosaic breccia, created when clusters of smaller stones are cemented in place by a different type of rock, is what gives the popular canyon its name. When the sun hits it just right, the canyon appears to glow.

Adam shuffled his feet up a near-vertical dry fall, boots sliding against slick marble as he ascended.

I couldn’t contain my smile as we clambered up the steep walls, laughing whenever one of us made a wrong move and nearly fell face-first into the rock. In spite of a head that felt like an anvil, I was floored by the unexpected beauty of the hike. The canyon’s walls narrowed, and soon we were squeezing through slot canyons freckled with a collage of pebbles. When we neared the final obstacle of the trek, a twenty-five-foot amphitheater of rock with no way to climb out, Adam inched over to the craggy wall, held out his pointer finger, and lightly tapped its surface.

“Boop. Thus ends the hike.”

“This hike shall henceforth be known as the most glorious in the whole of Death Valley!”

“And lo, on the first day of this desert park, it shall be decreed that the hike was good. And that I doth love you.”

We practically skipped our way out of the canyon the way we came, speaking in fake British accents and cracking Moses-era jokes about the day’s exploits. I was dizzy with sun and ready for more. Hopping back into Gizmo, we plotted a course for Artist’s Palette.

Earth’s nearest star began to sink toward the horizon as I rounded a bend onto Artist’s Drive, a one-way semicircular road that whisks travelers across crumbling umber cliffs to a hillside blotched with rainbow-colored minerals, as though Jackson Pollock grew three sizes and had a pastel field day with the landscape. Smudgy lumps of robin’s-egg blue and blush pink erupted across the mountains, and as the sunset intensified, Adam and I threw on our gloves and hats to tramp around in the wild expanse. I stilled myself in the chilly desert air by closing my eyes and taking deep breaths, inhaling and exhaling slowly as a light breeze tickled my cheeks. For the first time that day, I forgot my arduous schedule and my stuffy nose and began to feel something like peace.

***

Pick up your copy of Feral: Losing Myself and Finding My Way in America’s National Parks.

Discussion about this post