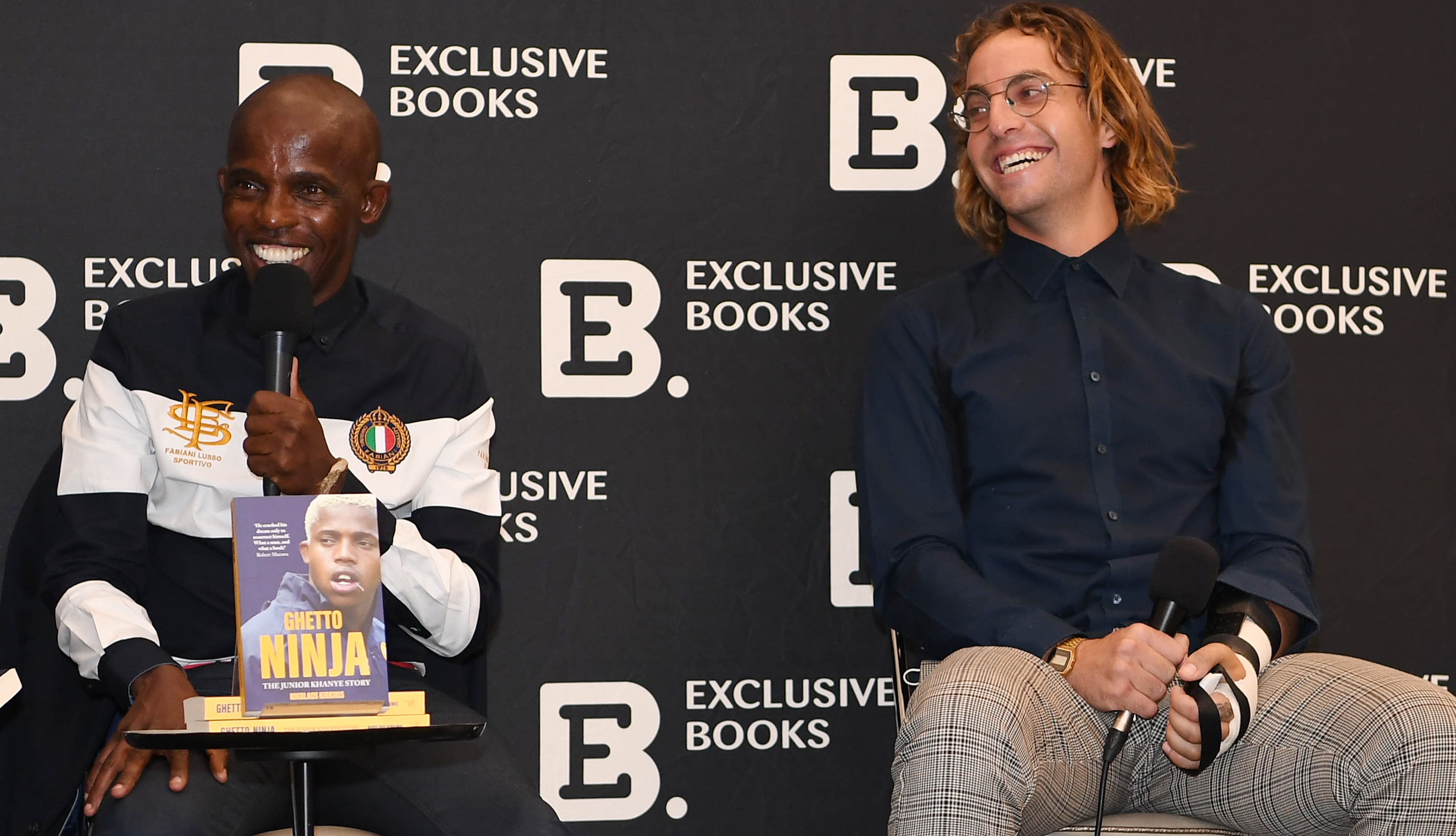

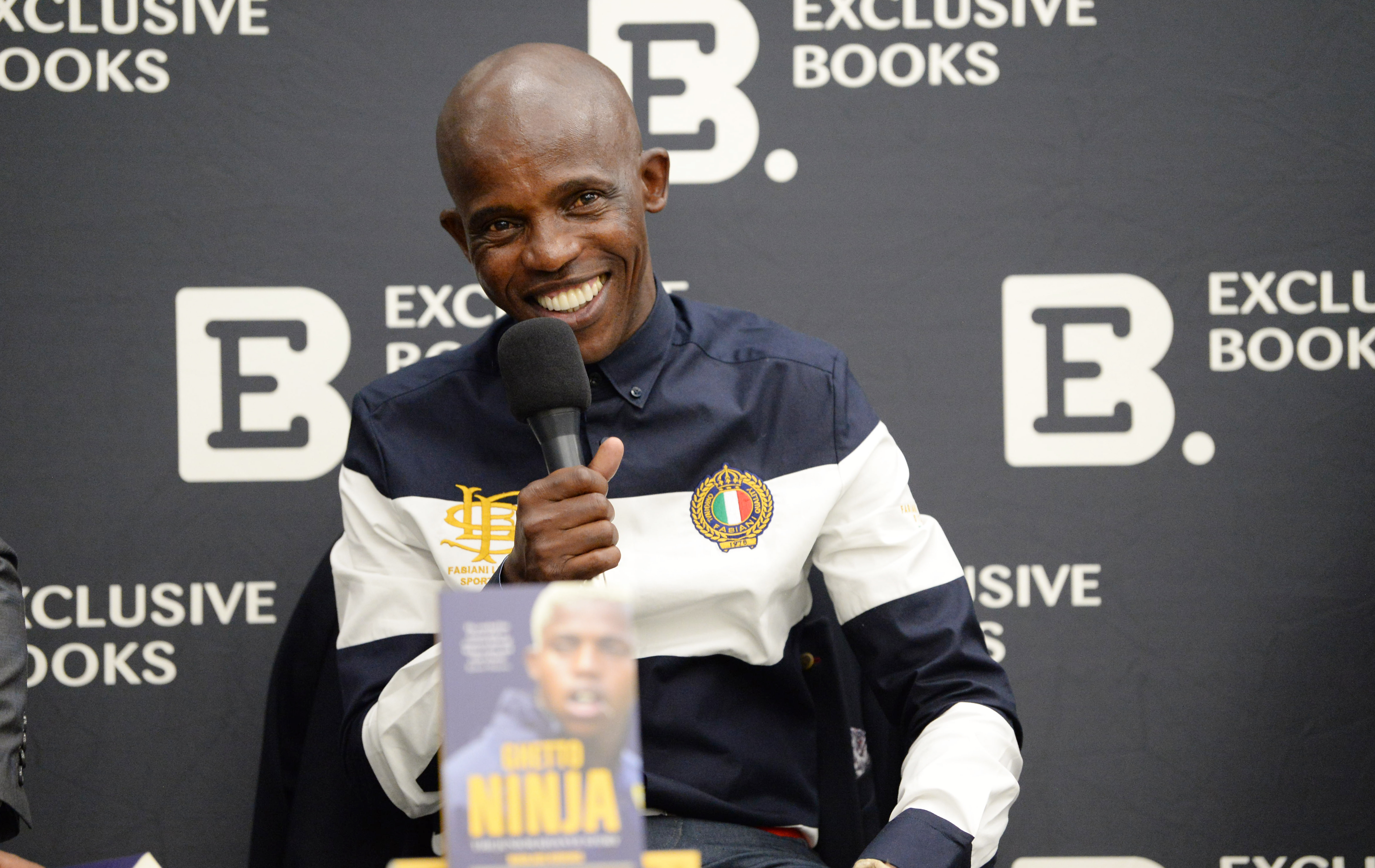

Nikolaos Kirkinis’s most recent sports biography, Ghetto Ninja: The Junior Khanye Story, is a gruelling, honest-to-the-bone story of the unique local football game, cushioned in the mishap of South African life.

Time and again, South African footballers burst onto the local scene with fat talent. They dribble, run and pass the ball on the green or gravel ground, moving swiftly, as if they are dancing. Word is that big things await them.

Then, they disappear; often, not to be heard of again.

The biography of former Kaizer Chiefs player Khanye tells the brutal story of the young soccer player’s rise from the township to glory – on and off the field – and his subsequent self-destructive fall back into the depths of poverty.

The biography gives a raw, easy-to-read glimpse into the disappearance of Khanye from one of the leading teams in the local Premier Soccer League.

It does offer hope, though. It also recounts the peculiar case of Khanye’s self-reinvention – sports commentator Robert Marawa called it his “resurrection” – finding himself back in the hearts of locals, this time as a community builder, a media personality, an actor and a dedicated father and husband.

A tale of tragedy

Wild stories of Khanye’s generation of soccer players fill the pages of the book, which was launched on 24 March. It is captivating, but there is no doubt the story is a tragedy.

The narrative plays out against the backdrop of poverty, which, the book makes clear, cannot be divorced from the tragedy of South African football.

All 271 pages plainly unpack the unique reality of our local game. They tell a wealth of bizarre stories coming out of South African sport, tales that are fit for Hollywood movies but most of the time only end up littering the streets.

“These stories are never recorded; they are never turned into books or into movies. They just get passed on from generation to generation and they die with the people that know these stories,” said author Kirkinis, who also wrote the bestselling The Curse of Teko Modise.

This is Kirkinis’s third sports biography and his second in the past two years. In 2021, he published Strike a Rock: The Thembi Kgatlana Story, a biography of the 25-year-old Banyana Banyana player who has become an international football icon.

Kirkinis, who worked as a journalist and editor for the biggest sports publication in South Africa, Soccer Laduma, published Ghetto Ninja within a little more than a year. He made sure things moved along quickly.

“In South Africa, we wait too long to get these stories out… the magic of it can get lost in the sands of time,” he said. The author, taken to Orlando Stadium as a five-year-old, is on a quest to inspire more people to get behind the beauty of the often disregarded local soccer game.

“Our football is a blend of art and science. It is not like English football, you won’t see solid German structure, or Italian defending in our football, but what you will see is our flair, our personality, our attitude come out on the field,” Kirkinis said. “These things are especially ours to adore, support and love.”

Getting the stories out there

Kirkinis comes from a generation of football fanatics who never had such books to read while growing up. “Local sports biographies just weren’t being written,” he said.

“People in this country, especially the youth, need [these books] now. So, it’s a duty to us in the [publishing] industry to make sure that we don’t drag our feet in getting these stories out.”

The ugly truth is that stories like this, about soccer talent that should have made it but instead fell, hitting the ground hard, are all too frequent.

Footballers die before their time in very preventable ways, or they are given into an off-field game of parties, spending and losing their way, Kirkinis said.

“Those of us who saw Junior play when he first came on the scene, as a 17-year-old, had never seen a player [with this much talent] like this before,” he said, adding that people thought he would play for Barcelona or Manchester United.

“There was no ways the kid couldn’t do the greatest things that a South Africa footballer can do,” Kirkinis explained. “He had such a unique approach to the game… He didn’t play like other players, he almost danced with the football – it was like he had come up with a new interpretation of football. He had turned it into an art almost.”

Condemned to the shadows

Unfortunately, a “classic” thing in local football happened.

“The off-field light took over, his naughtiness took over, he just couldn’t get out of his own way,” said Kirkinis.

It’s something that is heard a lot in local football, “usually when that happens, we just forget about the player. They are condemned to the shadows.”

“Some assumed that Junior was dead,” Kirkinis pointed out.

The book intimately recounts how Khanye’s decisions and actions led him from the limelight to dark moments in rivalry and poverty, living in a shack and going for two days at a time without meals.

“For someone to come back from this position is what makes Junior’s story unique.”

Initially, Kirkinis did not agree to write the story when the player approached him after they had appeared together on an SABC 1 TV show.

“I had the same opinion that others had: I thought he was a waste of talent,” Kirkinis recalled of the star whose poster once hung on his bedroom wall.

Home visit

Kirkinis again declined a request to tell Khanye’s story before he agreed to accompany the former star to his home in Daveyton.

After hearing his stories, it was clear “[Khanye] wanted his story to be out, warts and all, so that younger generations could learn from the things he had been through”.

“Yes, he did mess up a lot, and yes, he was a naughty kid, but he suffered great tragedies and his story was a particularly brutal one.”

Youngsters, soccer fanatics, those of us who have never seen a football pitch, could learn from Khanye’s stories.

Kirkinis spent two months immersed in Khanye’s life – meeting the family and community who were affected by the events described in the book.

“You hear stories about them but then you actually get to meet them. You can hear him talk about how he broke this woman’s heart, and it is just words. But when you stand in front of her and you look into her eyes, and you hear her tell the story with anguish in her voice – it becomes very real.

“You realise that this is more than just a story; this is people’s lives [that] have been affected.”

Khanye first shared his family’s dark times, the struggle with poverty, and admitted his mistakes (and apologised for them) in an interview with Marawa in February 2020 on the Marawa TV YouTube channel.

In the book, the author describes it as “one of the most iconic interviews ever held in sports history”.

It changes Khanye’s reception from the people who used to watch him in the stadium and on television, and hung his poster on their walls.

At the end of the interview, Khanye promises to share his story in greater detail one day. In Ghetto Ninja: The Junior Khanye Story, he candidly delivers. DM168

This story first appeared in our weekly Daily Maverick 168 newspaper which is available for R25 at Pick n Pay, Exclusive Books and airport bookstores. For your nearest stockist, please click here.

Related Articles

![]()

Discussion about this post