South Africa was born in war and its growth has been marked by catastrophes and ruptures, and it once again stands on a precipice.

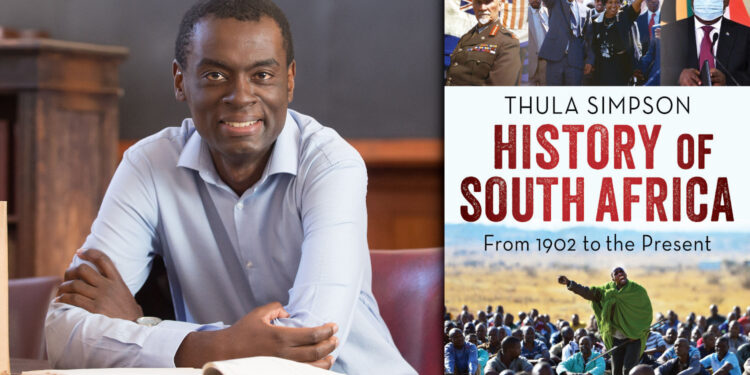

Thula Simpson’s new book, History of South Africa, explores the country’s turbulent journey from the aftermath of the Second Anglo-Boer War to the Covid-19 pandemic, tracking the influence of key figures with detailed accounts of definitive events.

The book draws on never-before-published documentary evidence – including diaries, letters, eyewitness testimony and diplomatic reports – following the South African people through the battles, elections, repression, resistance, strikes, insurrections, massacres, economic crashes and health crises that shaped the nation’s character.

Professor Xolela Mangcu from UCT’s sociology department calls the book “a masterpiece”, adding: “Narrative history at its best. With prodigious detail and eloquent prose Simpson places black South Africans at the centre of the country’s historical evolution and claims his place at the head table of contemporary historians.”

***

Read the excerpt

At the University of Cape Town on 6 June 1966, US senator Robert F Kennedy identified apartheid as one of many “differing evils” in the world, but told the students that each stand against injustice spread a “tiny ripple of hope” that could, with others, “build a current which can sweep down the mightiest walls of oppression and resistance”. To capitalise on the awareness raised by Kennedy’s visit, various American organisations including the American Committee on Africa and the National Student Christian Federation formed a Committee of Conscience Against Apartheid.

The committee’s principal goal was to achieve American divestment from South Africa, with the principal targets of its lobbying being First National City Bank of New York and Chase Manhattan.

The first American economic sanctions on South Africa were by the city of Gary, Indiana, in November 1975. In a racially polarised vote (six blacks for, two whites against), the council decided not to purchase goods from corporations that engaged in business with the Pretoria government. The American anti-apartheid movement expanded significantly after the following year’s Soweto uprising. The Reverend Leon Sullivan began gathering signatures from American businesses in March 1977 for a code of conduct to regulate their South African operations. The code included commitments to equal pay for comparable work, equal and fair employment practices, and workplace desegregation. Direct action was also initiated, especially on campuses, and by 1978 institutions including the Universities of Massachusetts and Wisconsin had voted to sell their shares in South African companies. On 22 November 1977, Polaroid became the first major American corporation to wholly divest from South Africa. The decision came a day after the Boston Globe, the company’s hometown newspaper, reported that one of Polaroid’s South African distributors was secretly selling camera and film equipment to the SADF and the Bantu Reference Bureau in Pretoria (which was responsible for issuing passbooks).

By the early 1980s, the campaign against apartheid had reached state and federal level. Massachusetts, Michigan and Connecticut all enacted disinvestment statutes in 1982, while the House of Representatives passed amendments to an Export Administration Act in October 1983 that would have banned all future US investments, outlawed the importation of Krugerrands, prohibited most loans to the apartheid government, and mandated adherence to the Sullivan Code.

The attempt to isolate South Africa extended into other spheres. In December 1980, the UN General Assembly passed a resolution calling for a cultural and academic boycott of the country. The UN established a blacklist of entertainers and sportsmen who ignored the boycott, but progress was initially slow. African American leaders such as the civil rights activist Jesse Jackson and the former US ambassador to the UN Andrew Young lobbied performers not to travel to South Africa, but by mid-1981, Ben Vereen, Gladys Knight and Roberta Flack were the only American artists of any significance to have refused bookings.

In 1978, the Southern Sun Hotel Group’s managing director, Sol Kerzner, had unveiled models for a hotel and entertainment complex in Bophuthatswana, and the project proved a major thorn in the boycott’s side. The venue, which opened officially in December 1979, catered to an overwhelmingly South African clientele (its main market in the Witwatersrand was located just over 100 kilometres away), and it attracted over a million visitors in its first year of operations. Sun City’s business model centred on its casino, which offered freedom from South Africa’s restrictive gambling laws, and its provision of live entertainment, with its heavy expenditure on the latter attracting leading performers from across the world. Frank Sinatra performed at the venue’s newly constructed Superbowl in July 1981, and the facility also became a major venue for sports events, including tennis, golf and boxing. To charges that the events breached the cultural boycott, Kerzner responded that Sun City was not in South Africa but in Bophuthatswana, where apartheid was not practised.

The retired tennis star Arthur Ashe and the actor and singer Harry Belafonte launched Artists and Athletes Against Apartheid in September 1983, to encourage performers not to play in South Africa and the homelands. The initiative’s sixty initial sponsors included Tony Bennett, Muhammad Ali and Jane Fonda. The organising committee vowed not to criticise people who had already performed at Sun City, and the approach offered a path to redemption for many performers at a time when criticism of apartheid was swelling. The number of cancellations by performers booked to play at Sun City soared.

Steve van Zandt (aka “Little Steven”), the former guitarist in Bruce Springsteen’s E Street Band, visited South Africa in October 1984 to assess the progress of the cultural boycott. The mid-1980s was a high point of celebrity philanthropy, with Africa the specific focus, and among the collaborative projects that ensued were Band Aid’s single ‘Do They Know It’s Christmas?’, which was released in December 1984; USA for Africa’s We Are the World, which followed three months later; and the Live Aid concert for famine relief in Ethiopia, which was held in London and Philadelphia on 13 July 1985. Van Zandt composed ‘Sun City’ during 1985, and to record the song he founded “Artists United Against Apartheid”, a protest supergroup including Springsteen, Bob Dylan, DJ Kool Herc, Bono, Afrika Bambaataa, Miles Davis, Peter Gabriel, Lou Reed and Jimmy Cliff. The record was one of the first fusions of R&B, hard rock and the new musical form of hip hop. The lyrics condemned (and offered an explanation for beginners of) apartheid and constructive engagement, and pledged “I ain’t gonna play Sun City”. The song was released in November, with the royalties being used to benefit the families of South African political prisoners.

The amendment to the Export Administration Act was killed in the Senate, but the township uprising in 1984 gave fresh impetus to the American anti-apartheid movement, and a combination of events around PW Botha’s Rubicon speech brought some of its longest-standing objectives within reach. The state of emergency had already shaken investor confidence. Chase Manhattan had over US$600 million in short-term loans to South Africa. The loans fell due at the end of every month, and were normally extended automatically, but on 31 July 1985, the New York Times reported that Chase’s chairman, Willard Butcher, had refused an extension. Further American banks followed suit, owing to fears that if other creditors demanded repayment, South Africa would struggle to meet its commitments. In so doing, they created the stampede they feared. The amounts demanded exceeded South Africa’s gold and foreign exchange reserves, and the Reserve Bank responded by buying dollars to meet demand, but the more it bought the more the rand sank in value.

This was the economic backdrop to the Rubicon speech. By the time of the address, South Africa owed about R36 billion in short-term loans to overseas banks. The speech caused the rand to plummet further, losing 20% of its value on 16 August alone. As recently as the first quarter of 1984, a rand was worth 81 US cents. Towards the end of August 1985 it fell to 34.80 US cents – its lowest-ever level. The losses induced the government to close the foreign exchange and stock markets from 28 August to 2 September.

On 1 September 1985, just prior to the markets reopening, the government froze loan repayments for four months to forestall renewed losses. The freeze, however, induced an attempt by creditors to seize money that American customers had paid to the New York branch of Nedbank (then South Africa’s biggest bank) for South African exports. If foreigners entered a new scramble to confiscate export proceeds, South Africa’s current account surplus would disappear, leaving it unable to service or repay its debts. The panic on the markets only subsided after a Reserve Bank statement on 5 September that it would honour the foreign debts of the country’s banks.

The rand had recovered to 39 cents to the dollar by the end of the week, but the economic damage would be lasting. If the rand was still worth about a dollar, foreign debt would be approximately 20% of GDP, but at 39 cents, the figure rose to 58% Having to devote more funds to debt repayment would mean sluggish growth, high interest rates, rising unemployment and increased insolvency – an economic recipe for political turmoil. As a senior South African banking source told the Sunday Times, Willard Butcher had effectively achieved what years of anti-apartheid marches and protests had failed to accomplish, by precipitating a panic that had much the same effect as a sudden imposition of broad economic sanctions. DM/ ML

Thula Simpson is an associate professor at the University of Pretoria. His earlier research focused on the ANC’s liberation struggle, and his first book, Umkhonto we Sizwe: The ANC’s Armed Struggle, was published in 2016. History of South Africa: From 1902 to the Present is published by Penguin Random House (R380).Visit The Reading List for South African book news – including excerpts! – daily.

![]()

Discussion about this post