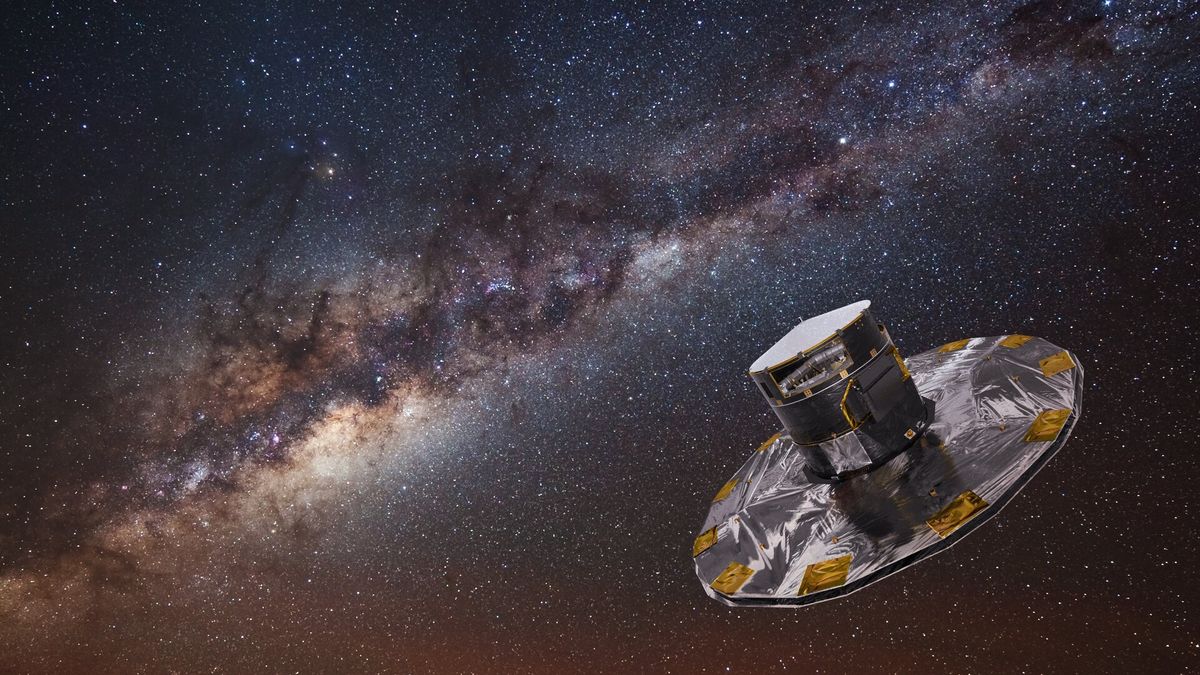

In a rare double-whammy space assault, the European Space Agency’s Gaia spacecraft was recently slammed by a micrometeoroid and struck by a solar storm, leaving it unable to function properly. But the satellite is now back to routine operations after the near-devastating impact, scientists say.

Gaia orbits at more than 932,000 miles (1.5 million kilometers) from Earth at what is known as the L2 Lagrange Point, where the combined gravitational forces of our planet and the sun create a stable orbit. The spacecraft’s goal is to create a 3D map of the individual stars in the Milky Way.

But in April, a meteoroid smaller than a grain of sand hit Gaia and damaged the protective shield surrounding its instrumentation. In the months since, sunlight sneaking through this tiny crack has disrupted the spacecraft’s sensors, according to ESA. In May, for unknown reasons, another piece of electronics failed — part of the system that enables Gaia to validate its detection of stars — resulting in thousands of false detections.

“Gaia typically sends over 25 gigabytes of data to Earth every day, but this amount would be much, much higher if the spacecraft’s onboard software didn’t eliminate false star detections first,” Edmund Serpell, Gaia spacecraft operations engineer at the European Space Operations Centre, said in a statement. “Both recent incidents disrupted this process. As a result, the spacecraft began generating a huge number of false detections that overwhelmed our systems.”

The second failure might have been caused by the same burst of solar particles from the sun that triggered widespread auroras around the globe in May, according to ESA.

Related: 13 billion-year-old ‘streams of stars’ discovered near Milky Way’s center may be earliest building blocks of our galaxy

Though there is little the Gaia team can do about the spacecraft’s hardware, they were able to patch its software to keep the spacecraft going, altering the threshold at which Gaia classifies an object as a star. The craft, launched in 2013, was originally designed to spend six years in space but has survived for more than a decade.

Gaia has previously helped astronomers detect the Milky Way’s oldest stars, which were born more than 12.5 billion years ago. The craft has also detected dim companions to major stars and a binary star system in which one star’s disk eclipses another. Data from Gaia has even given scientists an estimate of when the Milky Way will merge with its neighbor, the Andromeda Galaxy — indicating the colossal collision will occur 4.5 billion years from now.

Gaia is expected to continue collecting data until the end of 2025, when it will run out of gas in its propulsion system.

Discussion about this post