Photo: Alex Wong/Getty Images

It was April 9, 2009, and Wolfowitz, the former deputy secretary of defense in the Bush administration and one of the chief architects of the U.S. invasion of Iraq, had come to Arlington National Cemetery to celebrate the sixth anniversary of the fall of Baghdad.

He came to Section 60, the portion of Arlington where American soldiers who had died in Iraq and Afghanistan lay buried, as the most prominent guest at a small ceremony to mark the day six years earlier when the statue of Saddam Hussein in Baghdad’s Firdos Square had been pulled down. Wolfowitz and other Iraq war hawks had decided that April 9 should be commemorated as “Iraq Liberation Day.”

The 2009 celebration was organized and hosted by Viola Drath, a former journalist, longtime socialite, and, at 89, a tireless networker on Washington’s cocktail circuit.

She was now married to her second husband, Albrecht Muth, who claimed to be a general in the Iraqi Army. He wore his uniform to public events around Washington and possessed a certificate of his appointment signed by Iraqi Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki.

Using her Washington connections, Drath had managed to attract a smattering of VIPs to Section 60 for the Iraq Liberation Day ceremony, including both Wolfowitz and Iraq’s ambassador to the United States at the time, Samir Shakir M. Sumaida’ie.

Two years after that celebration in Section 60, Drath was found dead in her Georgetown townhouse. She had been strangled. Her husband, Muth, the supposed Iraqi general, was arrested for her murder. The certificate of his appointment as an Iraqi general was found to be a forgery; in Drath’s townhouse, police discovered a receipt from a Washington print shop where he had created the official-looking document. Muth was later convicted and sentenced to 50 years in prison.

Two decades after the March 19, 2003, U.S. invasion of Iraq, it is still difficult to peel back all the layers of deceit that enveloped the war. Some were thin and nearly transparent, like the fabricated generalship of Albrecht Muth. Others were enormously consequential, like the false assertion, peddled by the White House, the CIA, and the American press, that Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction. There was also much self-deceit, like the notion confidently shared by the war’s most ardent supporters that April 9 would forever be remembered as Iraq Liberation Day.

But one piece of deceit and disinformation stands out. Along with other official lies, it morphed into a lasting conspiracy theory that set a dangerous precedent and helped pave the way for the rise of Donald Trump: the assertion by the Bush White House that Saddam Hussein was behind 9/11.

Bush and his advisers saw the Saddam–9/11 connection as the silver bullet that could guarantee public support for an invasion of Iraq.

There was never any evidence that it was true, and the Bush administration knew it had nothing to support the claims. Yet the White House began to push the theory almost immediately after the September 11 attacks; President George W. Bush and his advisers saw the Saddam–9/11 connection as the silver bullet that could guarantee public support for an invasion of Iraq.

The Bush team pushed the false notion with such unrelenting ferocity during the 18 months between 9/11 and the March 2003 invasion that most Americans were soon convinced. Efforts by the press to debunk it made little difference. It was a powerful piece of disinformation that became so deeply embedded in the American consciousness that it was nearly impossible to dislodge.

The Bush White House was so successful that two years after 9/11, polls showed that nearly 70 percent of Americans believed that Saddam was involved in the attacks on New York and Washington. By 2007, despite the administration’s failure to find proof of the connection over the previous six years, polls revealed that one-third of Americans still believed it.

The equally specious argument that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction never enjoyed such a powerful hold on the American imagination as the belief that the war in Iraq could be justified as payback for 9/11.

It was a powerful piece of disinformation that became so deeply embedded in the American consciousness that it was nearly impossible to dislodge.

As with any good propaganda campaign, the Bush team was careful and lawyerly in making its case. In his public statements, Bush himself never explicitly said Saddam was responsible for 9/11; but he constantly used language in speeches and other public statements linking Saddam with terrorism, and he talked more broadly about connections between Iraq and Al Qaeda-style militancy. The Bush team did a masterful job of making it difficult for the public to distinguish between Saddam and Osama bin Laden. The public got the message that 9/11 and Iraq were inextricably linked.

The Bush White House kept pushing the false narrative surrounding a Saddam–9/11 connection despite resistance from the Central Intelligence Agency, where some officials were quietly furious at these dubious claims. In the run-up to the Iraq invasion, some CIA officials, speaking anonymously, told reporters that the intelligence didn’t support the White House notion of a Saddam–9/11 connection.

The battle between the Bush White House and the CIA over the intelligence on Saddam’s connections to 9/11 and terrorism consumed much of the 18-month interregnum between 9/11 and the Iraq invasion and turned increasingly bitter after Vice President Dick Cheney personally visited CIA headquarters and, along with his aides, began to pressure analysts to agree to the White House position. But the battle was waged almost entirely behind the scenes; it would surface only through occasional anonymous leaks to the press from CIA officials, accusing the administration of politicizing the intelligence, and conversely through statements from Iraq hawks close to the administration complaining about CIA intransigence.

The agency’s stance was badly weakened when CIA Director George Tenet refused to publicly engage in the battle, or even to criticize the Bush White House for pushing the Iraq–Al Qaeda link. At the time, Tenet’s hold on his job was fragile, and he believed he owed Bush for not firing him after the intelligence failures related to 9/11 prompted many critics to call for his ouster. In fact, there were several instances when CIA officials, speaking on background without attribution, would discuss the lack of an Iraq–Al Qaeda connection with reporters, only to see Tenet then publicly deny that there was any disagreement between the White House and the CIA, including when he was questioned by Congress. Tenet’s actions thus left CIA dissenters badly exposed to political pressure.

In the years since the U.S. invasion, this secret war between the White House and CIA over evidence of Iraq–Al Qaeda links has largely been lost to history, overshadowed by the subsequent debacle over intelligence on Iraq’s supposed weapons of mass destruction, and by the failure of the war itself. But the 2002 White House–CIA fight over Iraq–Al Qaeda intelligence nonetheless wreaked lasting damage, creating a model for Trump in how to build conspiracy theories around intelligence reporting.

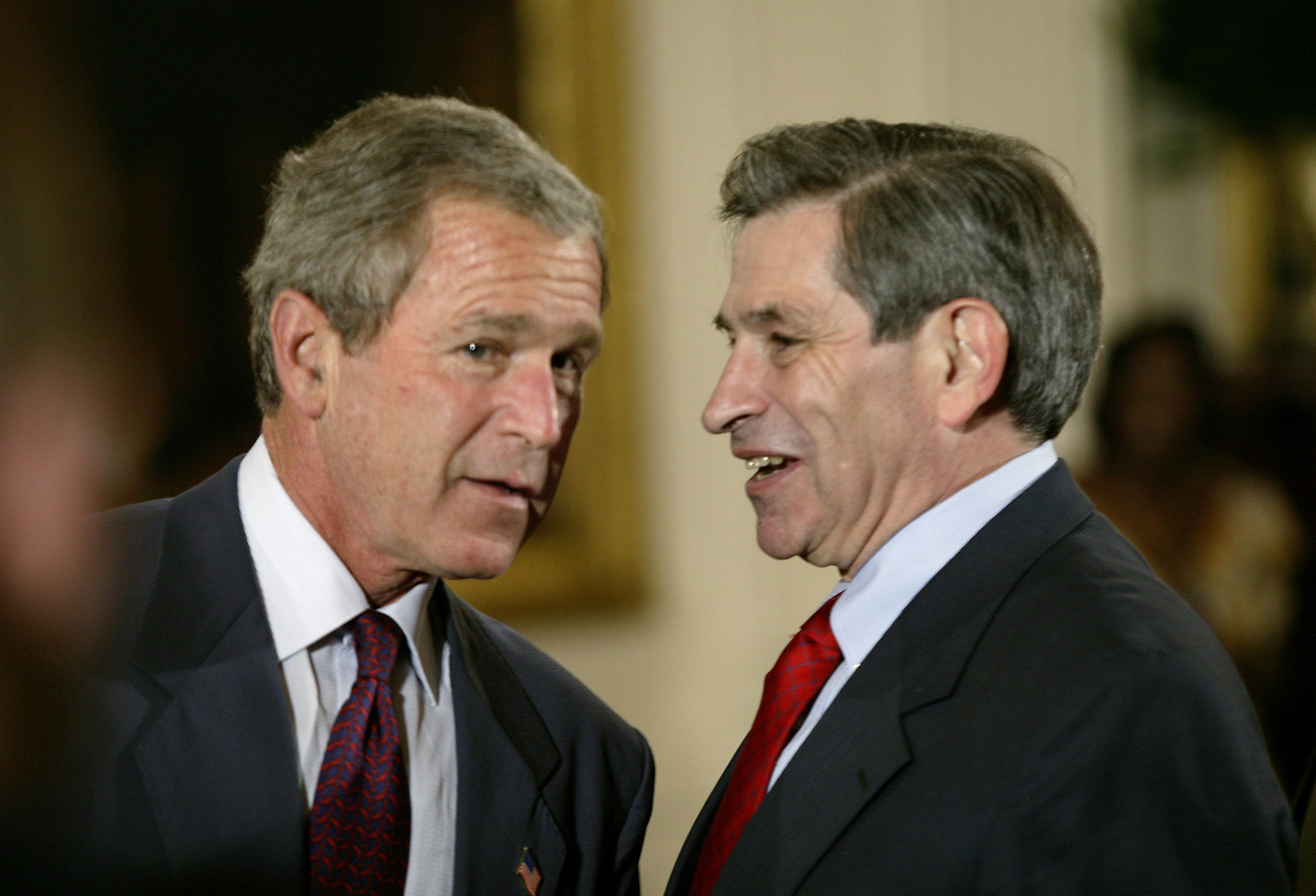

United States President George W. Bush talks to Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz July 1, 2003.

Photo: Corbis via Getty Images

Rather than concede that the CIA analysts might be right that there was no proof of Saddam–9/11, Iraq–Al Qaeda connections, the Bush team created a rival intelligence unit of their own to hunt for the evidence they claimed the CIA was ignoring. A two-man intelligence team, handpicked by Iraq hawk Douglas Feith, under secretary of defense for policy and one of Wolfowitz’s lieutenants, set up shop in the Pentagon and began scouring raw intelligence for signs of a connection between Saddam and Al Qaeda.

The amateurish effort was linked to Richard Perle, a leading neoconservative close to Wolfowitz, and a longtime critic of the CIA. Perle told me at the time that he thought the “people working on the Persian Gulf at the CIA are pathetic,” and that “they went to battle stations every time someone pointed to contrary evidence.”

Feith’s Pentagon team never proved their case. But the Bush White House became convinced they had found their silver bullet when they obtained a report claiming that Mohamed Atta, the leader of the 9/11 hijackers, had met with an Iraqi intelligence officer in Prague just months before the September 11 attacks.

Before long, the “Prague meeting” became the central piece of evidence used by the Bush team in their push for war. It seemed to provide the long-sought missing link between Saddam and 9/11. For the Bush White House, it was the perfect intelligence report.

The problem was that the meeting never happened. Yet the Bush White House kept peddling the story.

The battle to stop the White House from using the Saddam–9/11 connection to justify war with Iraq exhausted battered CIA officials and analysts. The fight so weakened the CIA that by the fall of 2002, Tenet and his top lieutenants were relieved when the Bush team finally began to switch the focus of its argument for war to Iraq’s possession of weapons of mass destruction.

Tenet was so intimidated by the fallout from the fight over the intelligence on connections between Iraq and Al Qaeda that he was eager to cooperate with the White House on WMD. After all, there were plenty of old intelligence reports, dating back to the 1990s when United Nations weapons inspectors had been in Iraq, that strongly suggested Saddam had WMD. There was even a sense of guilt that still ran through the CIA over the fact that, at the time of the Gulf War in 1991, the agency had failed to detect evidence of Iraq’s fledgling nuclear weapons program. That the CIA had almost no new intelligence on Iraq’s weapons programs since at least 1998, when U.N. weapons inspectors had been withdrawn from Iraq, was largely ignored by Tenet and most senior CIA officials; they didn’t want to admit that they had been dependent on the U.N. To account for a gap of at least five years in much of the intelligence reporting on Iraqi WMD programs, the CIA assumed the worst: that the weapons programs detected in the 1990s had only grown stronger and more dangerous.

Whenever intelligence was collected that countered this narrative, CIA officials discredited the sources or simply ignored it. In 2002, for example, the CIA sent more than 30 Iraqi American relatives of Iraqi weapons scientists back to Iraq to secretly ask about the status of Saddam’s WMD programs. All the relatives reported back to the CIA that their relatives had said that the WMD programs had long since been ended. The CIA simply ignored those reports.

By contrast, any new nugget of information suggesting that Iraq still had WMD was treated like gold dust inside the CIA. Ambitious analysts quickly learned that the fastest way to get ahead was to write reports proving the existence of Iraqi WMD programs. Their reports would be quickly given to Tenet, who would loudly praise the reporting and then rush it to the White House — which would then leak it to the press. The result was a constant stream of stories about aluminum tubes, mobile bioweapons laboratories, and nerve gas produced and shared with terrorists.

Dissent within the CIA over the WMD intelligence was much weaker than it had been on the Saddam–9/11 connection. Now, the hardy few critics of the intelligence were not only fighting the White House, but also their own management, which was fully on board with WMD. Whenever they were confronted by the few CIA skeptics who noted that the intelligence on WMD was thin, Tenet and his lieutenants would say that they “would find it when we get there” — after the invasion. And Tenet and his aides would point to Saddam’s refusal to meet Bush’s demands to allow Western weapons inspectors back into Iraq. That had to be proof that he was still hiding covert WMD programs; they never allowed for the possibility that Saddam was bluffing and didn’t want to admit his own weakness.

CIA Director George Tenet, left, and U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell speak following Powell’s address to the UN Security Council February 5, 2003 in New York City.

Photo: Getty Images

The CIA’s utter failure on WMD intelligence ultimately cost Tenet his job and poisoned American attitudes toward the war in Iraq. Yet the Bush administration’s persistence in pushing the obviously false narrative of a connection between Saddam and 9/11 may have had more lasting consequences for American politics. Bush set a precedent by officially sanctioning a conspiracy theory. His White House had engaged in a bitter battle with intelligence analysts, who Bush’s lieutenants and most ardent supporters saw as the enemy, to disseminate that conspiracy theory.

Bush set a precedent by officially sanctioning a conspiracy theory.

Donald Trump followed that model when he sought to convince Americans that he had won the 2020 presidential election, but that dark forces — including a “deep state” inside the U.S. intelligence community — had rigged the outcome to make Joe Biden president.

George W. Bush helped lay the groundwork for Trump to engage in conspiracy theories and spread them from the Oval Office. There is a direct line from the Prague meeting to “Stop the Steal,” and from March 19, 2003, to January 6, 2021.

Discussion about this post