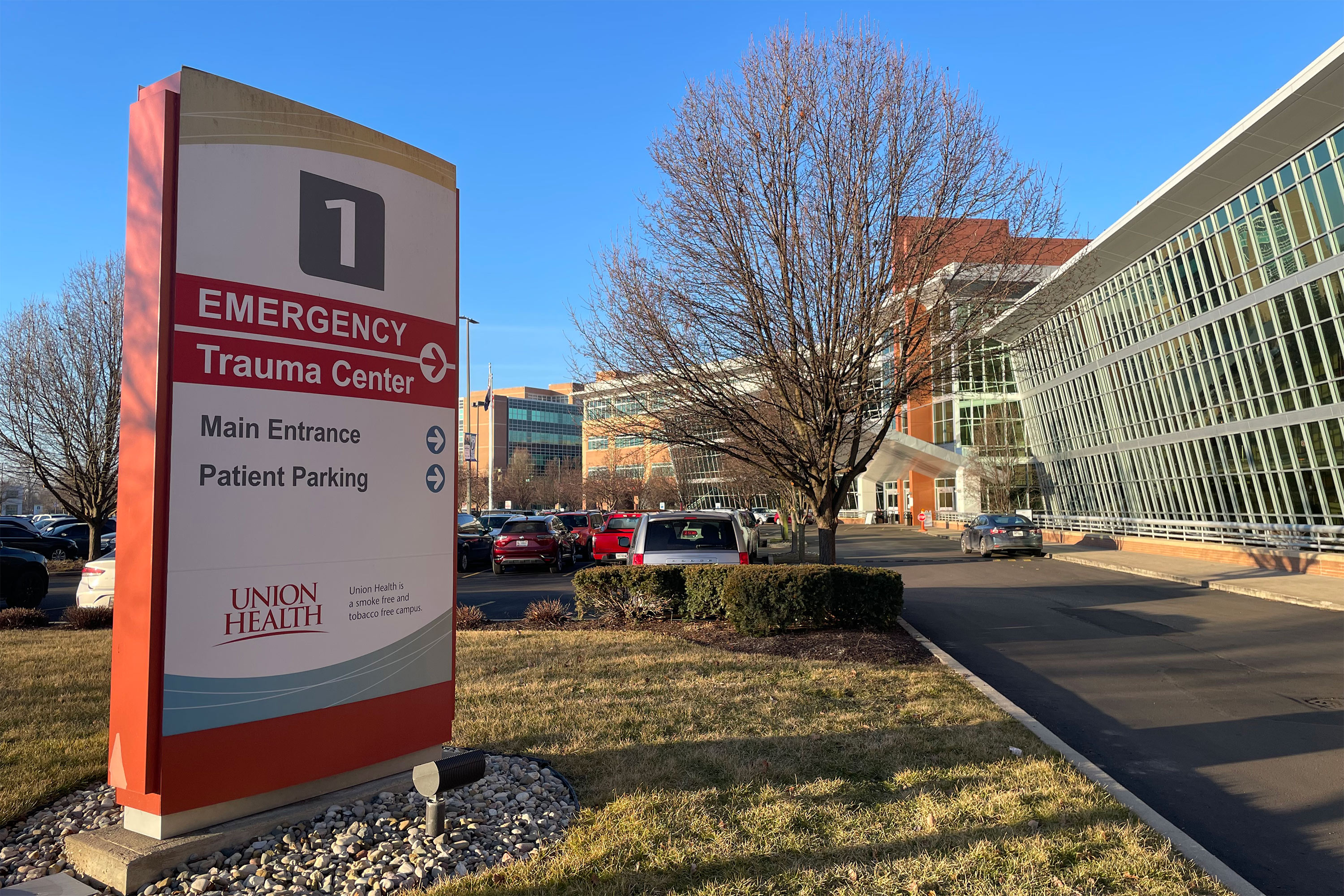

This image shows purified particles of mpox virus, formerly called monkeypox. Viruses like these can be genetically altered in the lab in ways that might make them more dangerous.

NIAID

hide caption

toggle caption

NIAID

This image shows purified particles of mpox virus, formerly called monkeypox. Viruses like these can be genetically altered in the lab in ways that might make them more dangerous.

NIAID

Over 150 virologists have signed on to a commentary that says all the evidence to date indicates that the coronavirus pandemic started naturally, and it wasn’t the result of some kind of lab accident or malicious attack.

They worry that continued speculation about a lab in China is fueling calls for more regulation of experiments with pathogens, and that this will stifle the basic research needed to prepare for future pandemics.

The virologists issued their statement just ahead of a key meeting Friday held by outside advisors to the federal government. That group is set to wrap up a recent review of the existing oversight system for experiments that are controversial because they could create new potential threats.

The advisors’ draft recommendations call for expanding a special decision-making process that currently weighs the risks and benefits of experiments that might make “potential pandemic pathogens” more dangerous.

“The government really has a strong interest on behalf of all of us, in the public, in knowing when researchers want to make a virus more lethal or more transmissible, and understanding how that would be done and why that would be done, and whether the benefits are worth it,” says Tom Inglesby, director of the Center for Health Security at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

He thinks if the draft recommendations were adopted by the government, “it would be a very big step forward.”

The origins of the pandemic

All of this comes as the lab in China, known as the Wuhan Institute of Virology, is again in the headlines. An internal government watchdog released a report this week criticizing the National Institutes of Health, saying it failed to adequately monitor grant awards given to a nonprofit that had collaborated with scientists at the Wuhan lab.

Felicia Goodrum, a virologist at the University of Arizona, says that open-minded experts have investigated the origins of the pandemic. The available evidence, she says, supports the notion that the virus emerged from nature just like other viruses such as HIV and Ebola did — by jumping from animals into people who had contact with them.

“The evidence that we have to date suggests that SARS-CoV-2 entered the human population by that route,” says Goodrum. “There is no evidence to the contrary or in support of a lab leak, nothing credible.”

Basic research on viruses, she says, is what led to the swift development of vaccines and drugs to fight the pandemic.

And yet virologists have watched in dismay as misinformation and conspiracy theories have placed the blame on science.

“There’s this complete disconnect between reality and what happened,” says Michael Imperiale, a virologist at the University of Michigan.

He says that while debates have gone on for years about the wisdom of doing experiments that might make bad viruses even worse, this moment feels different.

“The pandemic,” he says, “has really kind of heightened the urgency with which we need to address these issues, just because of all the controversy that’s been out there regarding, you know, was this a lab leak or not?”

A bird flu study raises alarm

Unlike, say, nuclear physics research, biology has traditionally had a culture of openness. After the anthrax attacks in 2001, however, biologists began to grapple with the possibility that their published work might serve as recipes for evildoers who wanted to make bioweapons.

And in 2011, there was an outcry after government-funded researchers altered a bird flu virus that can be deadly in people. Their lab work made this virus more contagious in the lab animals that are stand-ins for people.

Critics said they’d created a super flu. Proponents said that viruses sometimes have to be manipulated in the lab to see what they might be capable of; in nature, after all, mutations occur all the time and that is how pandemic strains emerge.

That episode marked the start of a long, heated debate, plus research moratoriums and ultimately the development of new regulations. In 2017, a review system was put into place to weigh the risks and benefits of studies that might make a potential pandemic pathogen even worse. So far just three proposed lines of research, with influenza viruses, have been deemed risky enough to merit that kind of extra scrutiny.

“We are really talking about a small amount of research proposals,” says Lyric Jorgenson, the acting associate director for science policy and the acting director of the Office of Science Policy at the NIH.

She says just before the pandemic started, officials asked advisors on the National Science Advisory Board for Biosecurity to consider whether the government needed to be more transparent to the public about how it was making decisions about this kind of research. Before that work was done, the pandemic hit and everything was put on hold. Last year, officials asked the group to broaden its work and to evaluate the regulations more comprehensively.

If the draft changes developed by this advisory group are eventually adopted by the government, an extra layer of oversight would apply to any study “reasonably anticipated” to enhance the transmission or virulence of any pathogen in a way that could make it a public health threat. That means more experiments on more viruses would get a closer look.

“What this new recommendation is saying, is that even if you start with a virus that had no potential to cause an epidemic or pandemic, if you are doing research that will change that virus in a way where it could now cause an uncontrollable disease, or a widely spreading disease, that has to be reviewed by this new framework,” says Inglesby.

What’s more, the advisory group has noted that “increased transparency in the review process is needed to engender public trust in the review and oversight processes.”

What’s “Reasonably Anticipated”

The American Society for Microbiology has responded positively to the draft recommendations, saying “we urge swift implementation of the recommended changes by the federal agencies engaged in this work.”

But some virologists think the devil will be in the details if these recommendations turn into policy.

“They keep using this phrase ‘reasonably anticipated,'” says Imperiale. “How is that going to be interpreted? Is there going to be clear guidance as to what is meant by that?”

Researchers often don’t know what will happen when they start an experiment, says Goodrum, especially when the science is cutting-edge.

“That’s where the big scientific advancements come from. And so to tie our hands behind our back, to say we can only do the science that we can anticipate, then we’re really restricting innovative science,” she says.

Ron Fouchier, the virologist at Erasmus University Medical Center in the Netherlands, whose lab did the bird flu experiments over a decade ago, said in an email that he’d hoped the experience of going through a pandemic would simulate more research, not “unnecessarily delay or restrict it.”

He said it looked like many infectious disease researchers in the United States “will face substantial delays in their crucial research efforts, if they can continue that research at all.”

The U.S. is unusual in that it has a lot of public discussion of these issues and a system to try to manage the risks, says Inglesby.

He thinks that oversight can be made stronger without getting in the way of science.

“I am avidly, absolutely pro-science and pro-research, and in particular pro-infectious disease research,” says Inglesby.

But he says there’s a very small part of that research “where there is the potential for very high risk if things go wrong, either by accident or on purpose. And so we have to get the balance right, between the risks that could unfold and the potential benefits.”

Discussion about this post