Recent research has produced detailed genomes of sex chromosomes for six ape species, showing significant variability and evolution on the Y chromosome. This work aids in understanding reproductive genetics and could impact studies of human diseases linked to these chromosomes. Credit: SciTechDaily.com

New end-to-end X and Y chromosome sequences uncover enormous variation on the Y chromosome, informing human evolution and disease as well as conservation genetics of endangered apes.

A collaborative research team has generated complete reference genomes for the sex chromosomes of several great and lesser apes, revealing rapid evolutionary changes, particularly on the Y chromosome. These findings provide a basis for future studies on ape reproduction, fertility, and sex-specific genetic traits, enhancing understanding of primate evolution and related human diseases.

Ape Sex Chromosome Research

An international team from Penn State, the National Human Genome Research Institute, and the

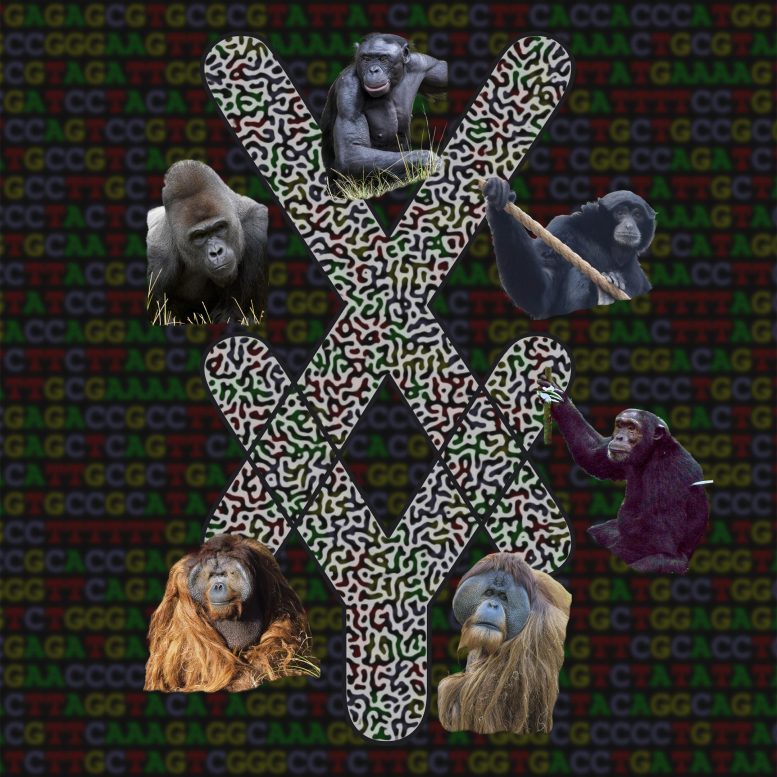

Newly generated, complete genomes for the sex chromosomes of six primate species — produced by an international collaboration led by researchers at Penn State and the National Human Genome Research Institute — reveal rapid evolution on the Y chromosome among apes. These results may inform conservation of these endangered species and shed light on sex-related genetic diseases in both humans and our closest living relatives. Credit: Design: Bob Harris; Photography: San Diego Zoo and Tulsa Zoo

Evolutionary Insights From Y Chromosome Variability

Such reference genomes act as a representative example that are useful for future studies of these species. The team found that, compared to the X chromosome, the Y chromosome varies greatly across ape species and harbors many species-specific sequences. However, it is still subject to purifying natural selection — an evolutionary force that protects its genetic information by removing harmful mutations.

The new study was recently published in the journal Nature.

Technological Advances in Genomic Sequencing

“Researchers sequenced the human genome in 2001, but it wasn’t actually complete,” Makova said. “The technology available at the time meant that certain gaps weren’t filled in until a renewed effort led by the Telomere-to-Telomere, or T2T, Consortium in 2022-23. We leveraged the experimental and computational methods developed by the Human T2T Consortium to determine the complete sequences for the sex chromosomes of our closest living relatives—great apes.”

Comparative Genomics of Great Apes

The team produced complete sex chromosome sequences for five species of great apes — chimpanzee, bonobo, gorilla, Bornean orangutan and Sumatran orangutan, which comprise most great ape species living today — as well as a lesser ape, siamang. They generated sequences for one individual of each species. The resulting reference genomes act as a map of genes and other chromosomal regions, which can help researchers sequence and assemble the genomes of other individuals of that species. Previous sex chromosome sequences for these species were incomplete or — for the Bornean orangutan and siamang — did not exist.

“The Y chromosome has been challenging to sequence because it contains many repetitive regions, and, because traditional short-read sequencing technology decodes sequences in short bursts, it is difficult to put the resulting segments in the correct order,” said Karol Pál, postdoctoral researcher at Penn State and a co-first author of the study. “T2T methods use long-read sequencing technologies that overcome this challenge. Combined with advances in computational analysis, on which we collaborated with Adam Phillippy’s group at the NHGRI, this allowed us to completely resolve repetitive regions that were previously difficult to sequence and assemble. By comparing the X and Y chromosomes to each other and among species, including to the previously generated human T2T sequences of the X and the Y, we learned many new things about their evolution.”

High Variability on the Y Chromosome

“Sex chromosomes started like any other chromosome pair, but the Y has been unique in accumulating many deletions, other mutations and repetitive elements because it does not exchange genetic information with other chromosomes over most of its length,” said Makova, who is also the director of the Center for Medical Genomics at Penn State.

As a result, across the six ape species, the research team found that the Y chromosome was much more variable than the X over a variety of characteristics, including size. Among the studied apes, the X chromosome ranges in size from 154 million letters of the ACTG alphabet — representing the nucleotides that make up DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-07473-2

In addition to Makova, Pál, Szpiech and Huber, the research team at Penn State includes Kaivan Kamali, computational scientist in the departments of biology and of biochemistry and molecular biology; Troy LaPolice, graduate student in bioinformatics and genomics; Paul Medvedev, professor of computer science and engineering and of biochemistry and molecular biology; Sweetalana, research assistant in the department of biology; Huiqing Zeng, research technologist in biology; Xinru Zhang, graduate student in bioinformatics and genomics; Robert Harris, assistant research professor of biology, now retired; Barbara McGrath, associate research professor of biology, now retired; and Sarah Craig, associate research professor of biology, currently a program officer at the

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/34/31/3431771d-41e2-4f97-aed2-c5f1df5295da/gettyimages-1441066266_web.jpg)

Discussion about this post