Expanding and decarbonising the world’s electricity supplies is key to meeting global climate goals – and this has been reflected in a series of recent pledges.

These include the COP28 deal to triple global renewable capacity by 2030 and agreement among the G7 group of major economies to end the use of unabated coal power by 2035.

These targets contribute towards the transition away from fossil fuels and aligning energy systems with the 1.5C limit, priorities that were also agreed at COP28.

However, the proliferation of power-sector targets creates a pressing need for timely data in order to keep tabs on progress.

The new Global Energy Monitor (GEM) global integrated power tracker (GIPT) makes it easy to track progress, bringing together the latest data on power-plant developments around the world.

This article introduces the GIPT and illustrates the sorts of insights it can generate, using the example of the G7’s pledges – and progress towards meeting them.

About the tracker

The GIPT is the culmination of a decade of work since GEM created its global coal plant tracker in 2014. It currently consists of a database of 116,095 power units and is free to use.

The GIPT is a Creative Commons database based on GEM trackers for coal, gas, oil, hydropower, utility-scale solar, wind, nuclear, bioenergy and geothermal, as well as on energy ownership.

GEM’s international team manually researches each power facility in the database using governmental, corporate and media reports, as well as satellite imagery. They work in Arabic, Chinese, English, Hindi, Portuguese, Russian and Spanish.

The data is updated twice per year and is also mapped to allow geospatial analysis, with each of the underlying trackers providing various summaries and dashboard information.

Coal phaseout

The G7 pledge to phase out unabated coal power by 2035 is seen as particularly significant for the US and Japan, who host the largest coal fleets in the group.

Data in the GIPT shows that coal power capacity in G7 countries peaked at 497 gigawatts (GW) in 2010 and has since fallen 37%, to 310GW of operational capacity at the end of 2023.

A continuation in the rapid decline in operating coal capacity in the UK, France, Italy and Canada will see these countries hitting their targeted coal phaseout dates before 2030.

The parties that make up Germany’s government wrote into their coalition agreement in 2021 that the 2035-2038 deadline for coal exit should “ideally” be brought forward to 2030. However, the coalition’s commitment to this ambition is far from assured.

Japan and the US, meanwhile, still have no explicit coal phaseout target. New rules from the US Environmental Protection Agency, requiring coal plants to capture 90% of their carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions by 2032, are expected to expedite plant closures.

If firm national targets for coal-exit years are followed – and assuming a 45-year average lifetime for coal plants in Japan and the US that lack a planned retirement year – then the G7 coal fleet would not be completely phased out until the middle of this century, as shown in the figure below.

Under this current outlook for retirements there would be a 77% reduction in G7 coal plant capacity by 2035 compared to today, leaving 72GW remaining.

Yet numerous assessments suggest that developed countries – such as those in the G7 – should completely phase out unabated coal by 2030, if the world is to limit warming to 1.5C.

This goal of an end by 2030 to unabated coal power could be achieved under an accelerated phaseout of G7 coal plants, whereby the average plant lifetime drops by 10 years, as shown in the figure.

Hiding within this average, however, is a considerable number of early retirements, mostly impacting coal-reliant G7 countries, particularly the US and Japan.

GIPT data show that, under this accelerated coal retirement case, some 28% of currently operating coal capacity in Japan – 15GW – would retire before reaching 20 years of operation.

Gas proliferation

Turning to G7 gas power, the GIPT shows that capacity grew by 55% over the past two decades. Gas is now the G7’s largest source of electricity and its leading source of power sector CO2.

This is despite the lower emissions intensity – the CO2 emissions per unit of electricity – of gas compared to coal, as well as the growing contributions from renewables, notably wind and solar.

Moreover, recent analysis suggests that electricity generation in developed countries such as the G7 should be completely decarbonised by 2035 to align with the 1.5C limit. This would mean phasing out unabated gas power by 2035, after shutting down coal by 2030.

Yet an additional 73GW of new gas-fired projects are currently in development across the G7, the majority of which are in the US, as shown in the figure below.

(The GIPT classifies “in development” projects as those that have been announced or are in the pre-construction and construction phases.)

The GIPT also includes information on the ownership structure of combustion power facilities.

An analysis of common parent entities underscores the way that many of these incumbent firms have made an apparent pivot from coal to gas, rather than leaving fossil fuels behind.

For instance, the top 100 companies for coal retirements in the G7 have brought 232GW of coal plants offline since 2000. Of these, 61 companies are also active in the gas power sector and have brought some 266GW of new capacity online since that date.

This near one-to-one switching appears to weaken when considering planned coal retirements and gas additions out to 2035. Yet of the 100 companies planning the most coal retirements by 2035, every 3GW of coal coming offline is still paired with 1GW of new gas capacity in development.

Tripling renewables

In terms of renewables, the G7 declaration “welcomes” the COP28 goal of tripling capacity globally by 2030, but does not adopt a specific target for the bloc or its member countries.

Nevertheless, it is clear that the countries of the world are collectively falling short of the tripling target, with the International Energy Agency (IEA) warning in June that they are on track to be 30% short of the goal in 2030.

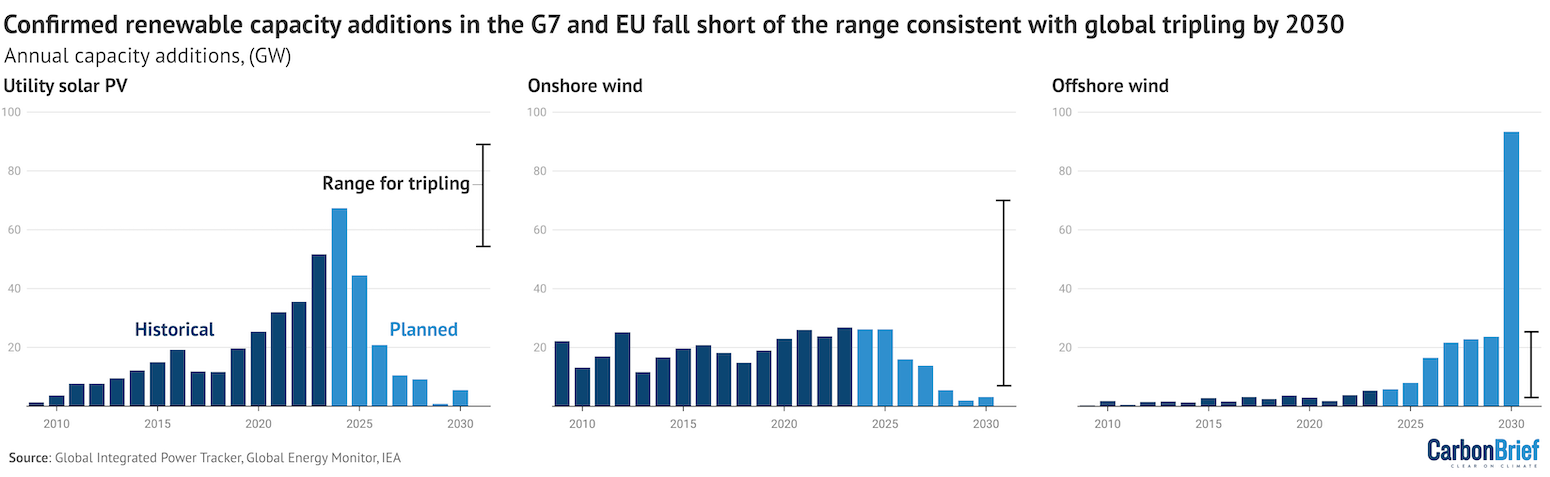

While the global tripling target has not been broken down into regional or national goals, the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) and the International Energy Agency (IEA) have calculated regional deployment ranges that would be consistent with getting on track.

Along with monitoring government targets for renewables expansion, tracking on-the-ground project developments can provide a sense of deployment progress.

The GIPT offers this capability by cataloguing project-by-project development statuses for existing and planned power facilities.

Across the G7 and EU, GEM data shows 181GW of utility-scale solar photovoltaic (PV) and 101GW of onshore wind projects with a planned start year before 2030. Most announced start dates for these projects fall within the next two years and are comparable to the record levels of installations in 2023.

If these projects start operating on schedule, then capacity additions for 2024 and 2025 would hit the bottom of the range of the annual levels of deployment within the G7 and EU. That would be consistent with tripling by 2030 globally, as shown in the figure below.

Beyond 2025, however, the GIPT suggests deployment rates for utility solar PV and onshore wind could drop below the range consistent with a tripling of capacity. This reflects the large number of “announced” and “pre-construction” projects that are yet to issue anticipated start dates, some 228GW for utility solar and 111GW for onshore wind.

For the G7 and EU to remain on track with the “tripling-consistent” deployment pathways beyond 2025, these as-yet undated projects would need to progress through various stages of conception, permitting and tendering to “shovels in the ground”.

In the case of offshore wind, a greater proportion of projects have anticipated start dates. Should these offshore projects reach commercial operation on time, then the deployment rates averaging 16GW per year sit within the range of deployment consistent with tripling.

On the other hand, the wind industry has faced numerous project delays and cancellations as a result of rising interest rates and increased commodity costs.

Indeed, 15% of offshore wind projects in the G7 were either cancelled or shelved between mid-2023 and mid-2024, with a further 22GW seeing slippage in anticipated commercial operation date.

Despite these challenges, a vast 303GW pipeline of G7 offshore wind projects sits in “announced” and “pre-development” stages, albeit without a target commercial operation date.

Converting around 3% of this project pipeline into operational wind farms per year would achieve a “tripling-consistent” capacity increase by 2030. Such a conversion rate was already seen between 2022 and 2023 across European countries.

Sharelines from this story

Discussion about this post