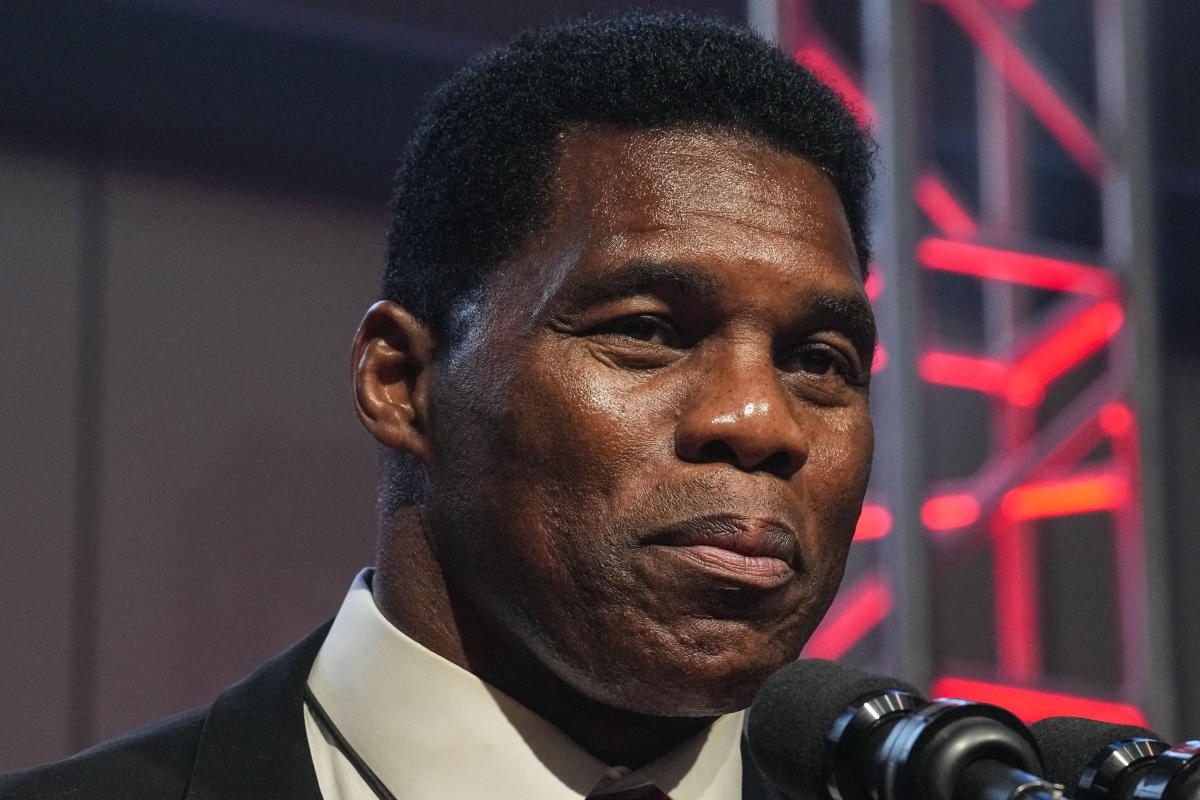

When Herschel Walker entered the U.S. Senate race with the backing of his longtime friend Donald Trump, Georgia Republicans were not naive about the challenges ahead. The retired football star had no prior political experience. He had a messy personal life, only some of which he had publicly acknowledged.

But as scandals involving domestic violence and abortion dribbled out over the summer and into the fall, something unexpected happened. Walker remained viable despite his flaws, his brand equity pulling him nearly even on Election Day in November.

“That image helped him survive the punishing onslaught that he received,” said Steven Law, head of the Senate Leadership Fund, a conservative super PAC. “I mean, I think a lot of other candidates would have been out of the running.”

But on Tuesday evening, Walker’s ability to stay afloat politically ended. He became the latest GOP candidate to fail to secure a Senate bid, falling to Democratic incumbent Sen. Raphael Warnock in the state’s runoff election.

“He should have never run for this seat,” said a person close to the campaign. His campaign loss, the person said, is largely because “Herschel had a ton of baggage he was not transparent about, and we were constantly behind the eight ball.”

In the end, Walker remained a strong and viable challenger, losing to Warnock by what is likely to be just a couple percentage points when the final votes are tallied. The margin was close enough that the quality of Walker’s campaign mattered.

Interviews with a dozen campaign staff members and Republican operatives working with the Walker campaign suggest that it wasn’t just the candidate who had flaws — the campaign itself was hampered by poor decision-making.

Some said that Walker and his wife, Julie Blanchard Walker, never fully empowered his team to make decisions, frequently questioning suggestions and plans by veteran campaign operatives. The pair insisted on spending what aides described as an “excessive” amount of time poring over proposals for every campaign stop, bottlenecking planning. That included wanting to spend significant time in heavily Democratic areas to woo Black voters, a problem that worsened in the runoff when staff wanted Walker to focus exclusively on mobilizing Republicans who had just voted for him in the general election.

Staffers said Blanchard Walker even suggested her husband should be winning as much as 50 percent of the Black vote in Georgia, regularly commenting that the campaign needed “to be getting him in front of his people, in front of his community,” as one person working on the campaign recalled.

A Republican victory in the Georgia Senate race — even with a Black nominee — was unlikely to involve the party winning over droves of Black voters. The overwhelmingly Democratic demographic propelled Warnock to office two years ago.

“She thought we should be getting amounts of African American voters that no Republican in the history of modern politics has ever gotten,” said a person close to the campaign. “And that became an obsessive focus.”

Some of Walker’s final events seemed puzzling and ill-conceived — in one case, coaxing bystanders to come onto his bus and meet him during a rainy SEC championship tailgate in Atlanta; the next day, spending an hour parked outside a bar where Green Bay Packers fans were gathered, offering to take photos with them. Around 20 fans took Walker up on the offer.

Throughout the campaign, the couple also declined to share control of Walker’s personal, nearly 1 million-follower Twitter account, which his wife solely operated.

The Walker campaign, for many on it, was an abject lesson in how difficult it is to translate celebrity into political advantage. Walker’s campaign staff described him as someone willing to learn and accept criticism. He was clearly not an expert on many policy matters, they said, but he asked questions and tried to improve his stump speech over time.

But there were limits. Towards the end, the campaign embraced the strategy of pairing him with another senator in interviews on Fox News, in particular Sens. Lindsey Graham and Ted Cruz. The set up was designed to allow Walker to focus on appearing more “senatorial.” It also was done to ensure that someone remembered to make fundraising appeals to viewers.

And while Walker enthusiastically took every photo and signed the ballcaps of every supporter who lined up at his events, his campaign eventually ran out of steam. Staff who had assumed they’d be busy on the campaign trail the week around Thanksgiving came to realize that there was nothing planned. For five critical days — as early voting opened — Walker avoided any public campaign events, instead holding fundraisers on Zoom, attending a funeral for Georgia Bulldogs coach Vince Dooley, attending a birthday party for his mother and traveling to Dallas for an event with high-dollar donors.

“There’s no excuses in life,” Walker said to his election night crowd, as he conceded defeat. “And I’m not going to make any excuses now, because we put up one heck of a fight.”

Like many new entrants into national politics, Walker struggled to build cohesion among the staff tasked with guiding his election. There was, aides said, constant friction between them and his family.

Blanchard Walker also tried to influence campaign strategy at critical moments, staffers said. During a Gloria Allred press conference on Nov. 22 featuring a woman who had accused Walker of pressuring her to get an abortion, Walker’s team was preparing for damage control and to even go on the offensive about the woman’s claims. But Blanchard Walker urged them, instead, to prioritize responding to a tweet Warnock’s campaign had just posted, featuring a video clip of one of Walker’s assistant high school football coaches endorsing Warnock. The team of staffers were told to call around to Walker’s other high school coaches, trying to persuade them to provide quotes praising the former football player.

But many of the hurdles that confronted the Walker camp were caused by Walker himself.

The former Heisman trophy winner struggled mightily on the stump. That included during the runoff, when he went on a fairly lengthy tangent about the differences and respective benefits of being a werewolf and a vampire — a viral moment that seemed to reinforce his shortcomings as a candidate.

His aides and allies said the episode was not as nonsensical as the media made it out to be. But they did say that staff this fall started asking Walker to workshop his lengthy, metaphorical stories with them before using them in public.

As it became clearer that Walker would likely lose in the runoff, some Georgia Republicans began openly expressing buyer’s remorse. GOP strategist Dan McLagan, who worked on the Senate campaign of Walker’s primary challenger, Gary Black, maintained that Black would have won the general election handily. Walker trounced Black, the outgoing state agriculture commissioner, in the May primary.

“Georgia is a red state when we pick the best candidate rather than the rich one or the celebrity,” McLagan said. “Until we learn that lesson, we will be treated to more train wrecks like this one as our nominee gets vetted in the general election like a slow motion Spanish Inquisition.”

But the recriminations from Walker’s loss seem likely to extend well beyond the state boundaries. Senate Republicans were left to face questions about how they had managed the race and whether more resources could have been expended.

National Republican Senatorial Committee officials questioned why the Senate Leadership Fund, the spending group aligned with Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, wasn’t faster to buy ad time during the runoff. SLF allies suggested the committee’s fundraising tactics and financial management left candidates without enough support.

An NRSC staff member said the committee spent “millions” on the runoff, but declined to elaborate further. Publicly available ad-tracking data shows the NRSC spending just $500,000 on a television advertisement at the start of the runoff. And a person close to the Walker campaign said it did not appear the NRSC dished out significantly more in the runoff beyond the cost of the early ad, though the committee placed staffers on the ground in Georgia the last few weeks.

Senate Leadership Fund spent $18 million in the runoff election, the super PAC confirmed to POLITICO. Of that, $2.5 million went to running a ground game operation developed by Gov. Brian Kemp’s team, with the rest buying TV, radio, digital and mail advertising spots, along with texts and calls to voters.

Those numbers were a fraction of spending by Warnock and his allies. Of the $82 million spent on runoff ads, according to AdImpact, $56 million was from Democrats, compared to just $26 million by Republicans.

But the person who seems likely to take a lion’s share of the after-the-fact criticism for Walker’s failure was Trump. The former president’s record in the 2022 midterms had been porous prior to Tuesday evening, and Walker was widely viewed as his main recruit. Walker’s son, Christian, tweeted on Tuesday evening that the former president had demanded his father get into the race.

Others close to Walker, though, said Trump’s role in his run was overstated. Even so, they conceded, the narrative had largely been set and the former president would likely take the blame.

“The idea that the origin story of Herschel’s candidacy was Trump calling him up and telling him he should run for the Senate, that is not accurate,” said a person close to Walker, with knowledge of his early discussions about running. “But you’re not going to get anybody to say that on the record. And the reason why is because it kind of sounds like you’re being disrespectful of the president.”

Discussion about this post