Donald Trump walked out of a Miami courtroom following his not-guilty plea Tuesday and into a looming thicket of legal peril.

The former president faces a frightful prospect: potentially decades in prison, a de-facto life sentence for a 77-year-old man accused of illegally hoarding, showing off, and lying about top-secret documents. He faces 37 criminal charges in federal court.

There are several ways Trump could walk free. They involve a delay, a jury, a judge, and legal arguments touching both procedure and substance.

Here are his four potential paths out of legal peril, according to analysts.

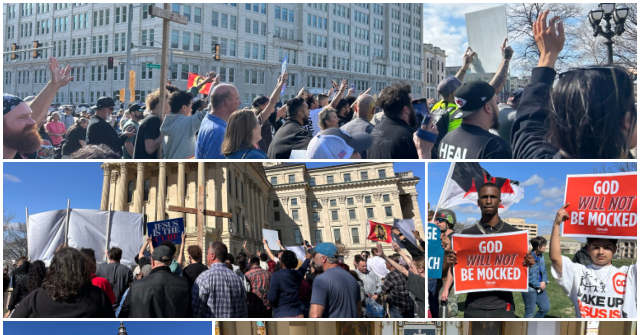

Donald Trump’s historic arraignment on federal charges drew crowds of supporters and turned Miami into a boiling cauldron of outrage and defiance. It also gave Trump another springboard to prominence in the 2024 presidential race.

Path 1: Delay

Trump has an incentive to punt this case beyond 2024, until after the U.S. presidential election, and hope that either he or an ally is running the Justice Department starting on Jan. 20, 2025.

A Republican president could overturn the case with a pardon — or with the dubious, unprecedented and untested step of Trump trying to pardon himself, if he runs and wins.

This is destined to become a central election issue for the next 17 months — both in the Republican primaries, and then in the general election if Trump is the nominee.

One longshot Republican candidate, Vivek Ramaswamy, stood outside the courthouse Tuesday and promised a Trump pardon on Day 1 if he’s elected president.

Prosecutors say they want a quick case.

Holding the trial in Florida might help. The average criminal case length in South Florida is nine months, half the length of a case in Washington, D.C.

“It could be tried as quickly as November of this year,” Richard Gregorie, a former Miami prosecutor and assistant U.S. attorney in the Southern District of Florida, told CBC News.

Emphasis on the word could.

Gregorie added a caveat: If parties want to drag it out beyond the primaries early next year, and into the November general-election season, they can.

It depends on how many motions they file and on how many fights there are over evidence. “This could be drawn out for some time,” Gregorie said.

Path 2: Fight the evidence

The case sounds devastating. One memorable example from the 49-page indictment is a detailed transcript of a recorded conversation where Trump allegedly incriminates himself.

But presumption of innocence is a cornerstone of the U.S. legal system. Trump will challenge the evidence on multiple fronts, as is his right.

He’s expected to argue that certain evidence is inadmissible. Like notes from his lawyer, which authorities obtained after convincing a court there was evidence that Trump had been counselling crimes.

He could also try getting the case dismissed. Remarks from him and members of his legal team suggest they’ll argue there was prosecutorial misconduct.

Trump lawyers have, in several media interviews, been citing reports that a lawyer for Trump’s personal valet, who is also charged, claimed to face threats from the Justice Department.

Their allegation: the valet’s lawyer was told that he would lose a judgeship nomination if he didn’t persuade his client to turn on Trump and become a witness for the prosecution.

“[They] extorted a lawyer,” Trump lawyer James Trusty told Fox News. Last week, Trusty quit working on the case but has been defending Trump in media interviews.

The procedural fights aside, Trump’s team will argue against the substance of the case.

Trump’s allies have been alluding to a broad potential defence: that the president has unlimited power to declassify documents.

That power, they allege, is so boundless that the mere act of his taking them from the White House means they’re no longer classified.

Trump allies have cited a 1988 Supreme Court case involving the Navy and a 2012 case involving Bill Clinton, where a right-wing group sued for access to Clinton audio recordings.

This is sheer nonsense, say some legal observers.

Trump critics say there’s no comparison between others’ behaviour and the way he allegedly hoarded – then lied about – documents stamped with top-secret markings.

A former Obama-era official also ridiculed it in a piece for CNN titled: I Wrote The Declassification Rules, And They Leave Trump Largely Defenseless.

Lawrence Douglas, a law professor at Amherst College in Massachusetts, told CBC News: “These aren’t arguments that are going to fly at all.”

Path 3: The judge

If all that fails, Trump will hope for friendly rulings from the judge.

The judge currently overseeing the case was appointed by Trump and is a member of the conservative Federalist Society.

She sided with Trump in an earlier decision, when he tried slowing the investigation. Her pro-Trump ruling was excoriated by another (higher) conservative-leaning court as a radical reordering of constitutional principles and counter to obvious law.

Now that judge, Aileen Cannon, has considerable power.

The daughter of a Cuban exile, the Colombian-born judge was a newspaper writer for the Spanish-language Miami Herald, a defence attorney, and a prosecutor, before Trump appointed her in 2020.

An unsealed indictment revealed 37 charges against former U.S. president Donald Trump, related to national security for improperly stashing classified documents, showing them off and then lying to authorities about them.

A judge’s clout comes in several forms.

The judge can decide what evidence the jurors hear – say, for instance, whether Trump’s lawyer’s notes are admissible in court.

She can dismiss certain jurors.

Later on, if the jury is struggling to reach a verdict, she can declare a mistrial, rather than force jurors to keep deliberating.

Then there’s the ultimate power move, a rarely used one: Judges can essentially snap their fingers and declare the trial over, with the accused acquitted.

Known as a Rule 29 motion of acquittal in the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, a judge can toss out a case for insufficient evidence at various points in the trial.

The government couldn’t automatically appeal. It depends on whether this judge’s ruling came before or after a jury’s verdict.

If it happened before the verdict, one law professor at the University of California, Berkeley, Orin Kerr, in a colourful tweet, described how Trump could be set free with just a few words from the judge: “You are the greatest president in history, and I hope you are re-elected. Rule 29 motion granted.”

In other words, she could bypass the jury.

Path 4: The jury

Speaking of that jury, the math on jury deliberations places the federal government at one significant disadvantage.

One holdout juror has greater power than 11 wanting to convict. Prosecutors need a unanimous decision of 12 jurors. Trump doesn’t.

“All you really need is to have one, let’s say, diehard Trump supporter who believes the whole thing is a witch hunt… And you are basically unable to convict in that circumstance.”

He alluded to one challenge in this case: finding 12 impartial jurors for one of the world’s most famous people, about whom everyone has an opinion.

For what it’s worth, the trial is happening in a politically divided area.

In 2020, Trump won nearly half the votes in Palm Beach County. It’s way more than his 5 per cent in another potential trial venue: Washington, D.C.

Focusing on Donald Trump’s legal problems is not the way for U.S. President Joe Biden to win re-election, says Roger Fisk, a former advisor to former U.S. president Barack Obama.

Whatever happens in this case, Trump has legal headaches on multiple fronts.

He also faces charges in New York, and there’s a potential case in Georgia. This was underscored Tuesday. While Trump was in a Florida court, a grand jury was meeting in Washington, investigating his behaviour in the runup to the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol.

But back in the south of Florida, 12 jurors, one judge, and a few lawyers will shape a high-stakes political outcome.

They’ll decide whether Donald Trump spends his final years in prison. Or whether he’ll emerge a free man, seeking to reclaim a position they used to call leader of the free world.

(2023)

(2023)

Discussion about this post