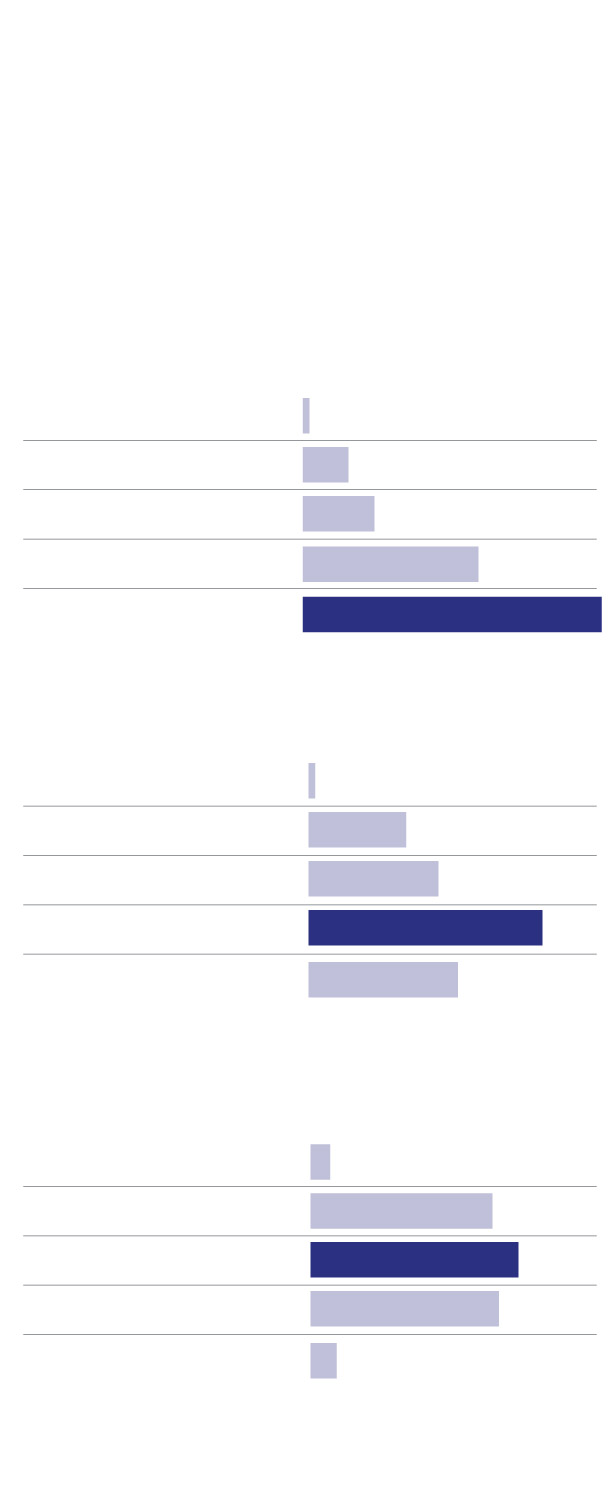

Nearly three-quarters of the public believes that the country is worse off than it was 14 years ago, the London-based pollster YouGov has found. More than 46 percent of people say it’s “much worse.” And to some extent, economic and other data back that up.

Scottish independence

referendum

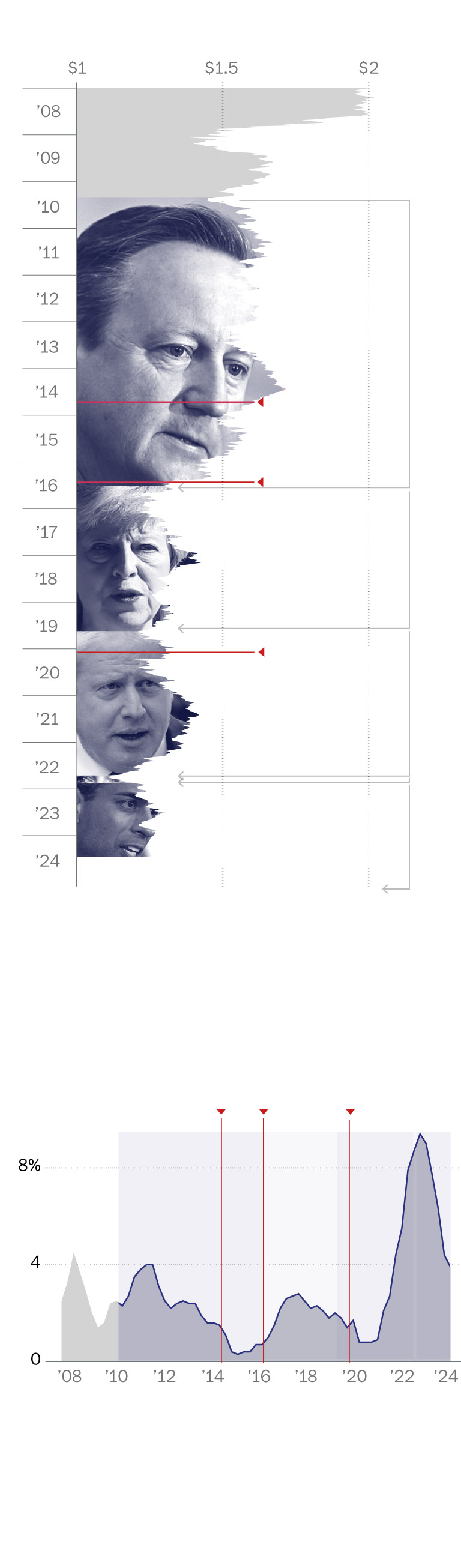

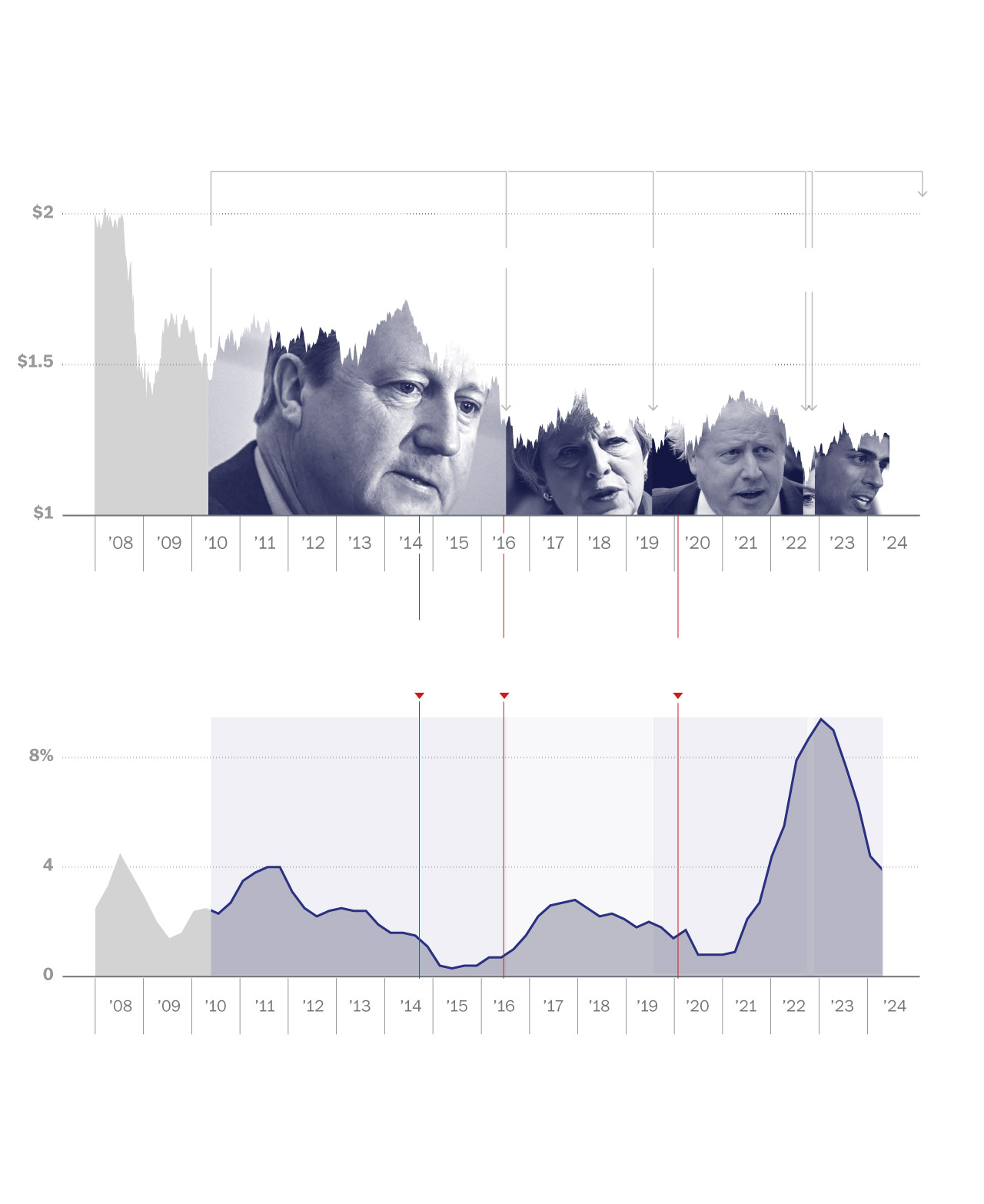

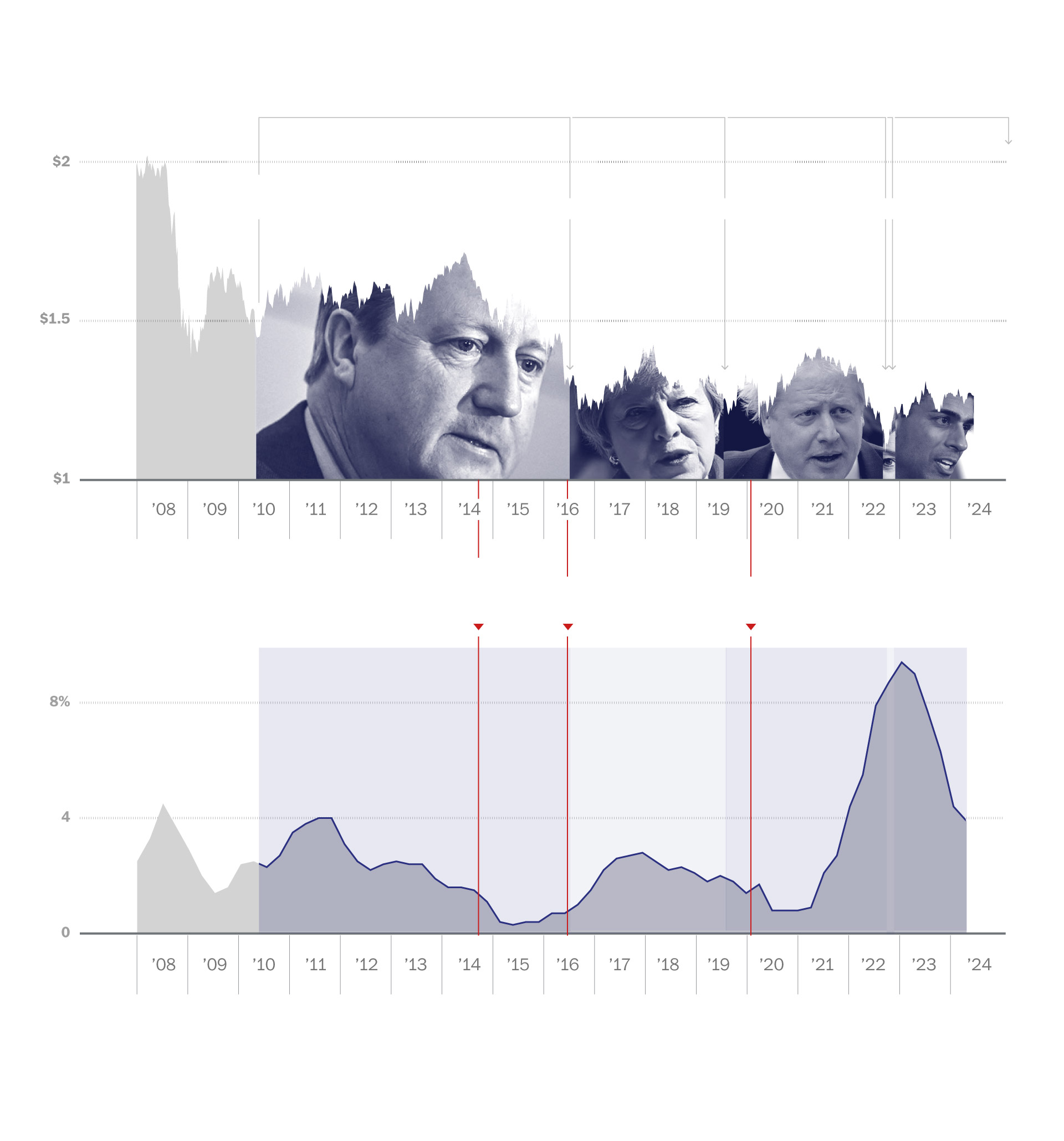

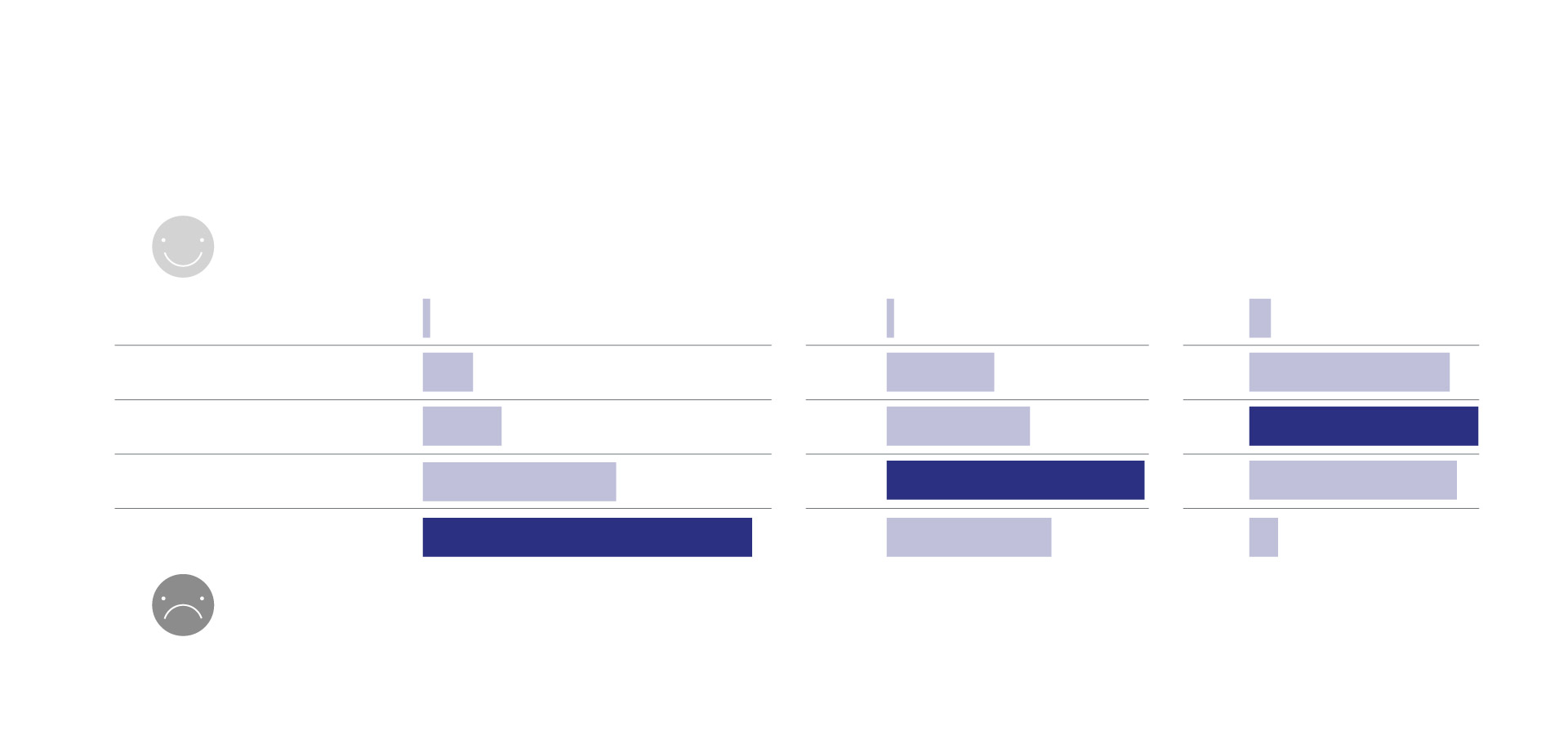

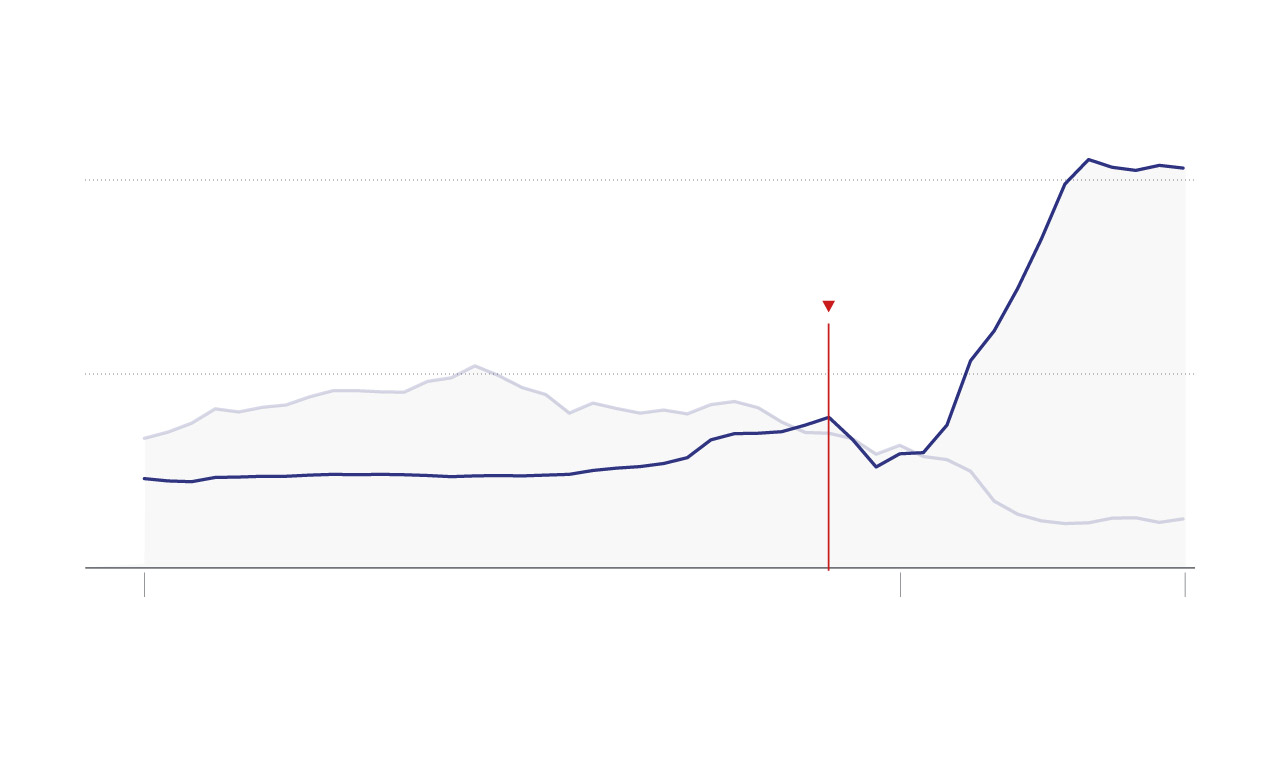

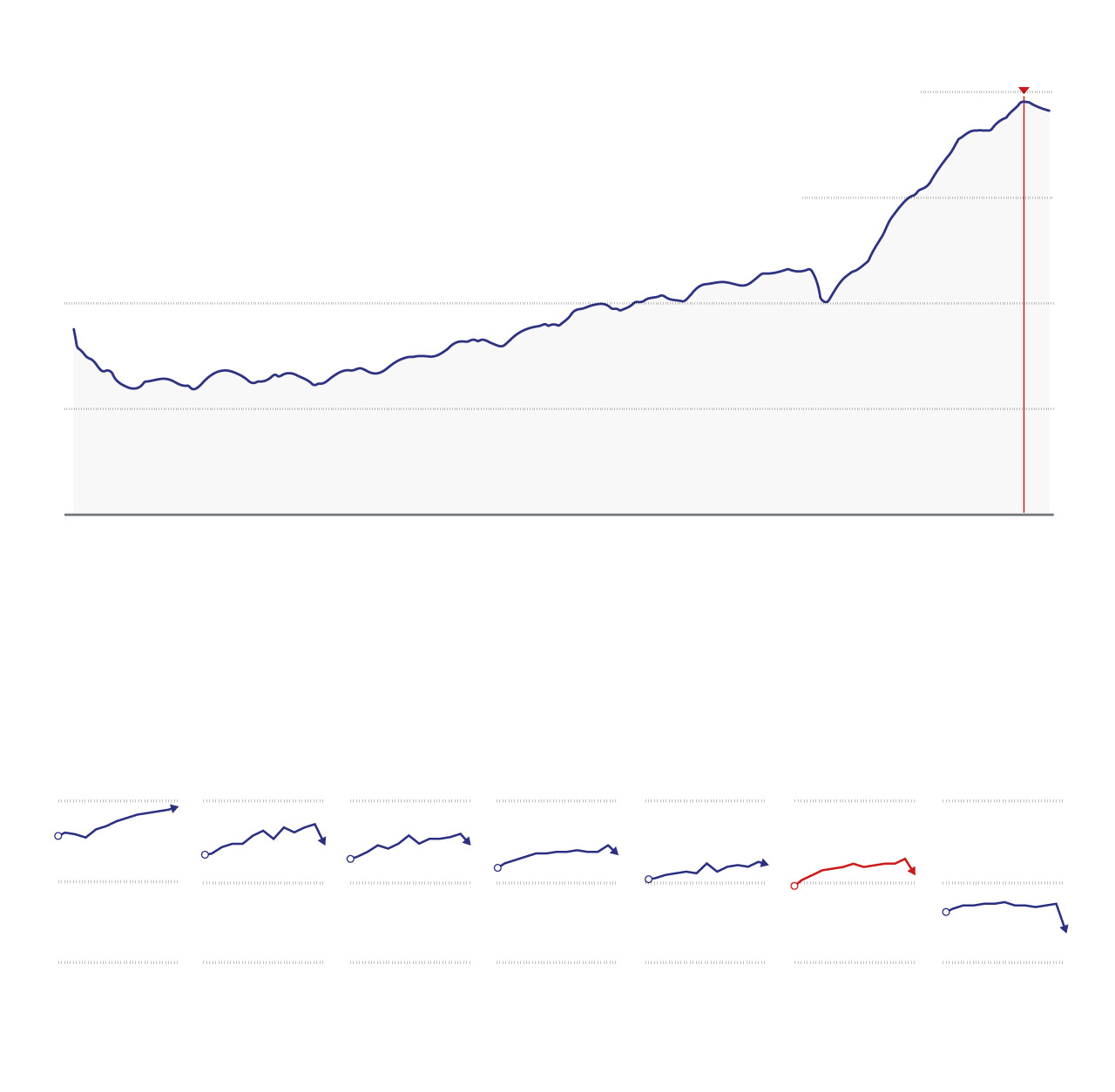

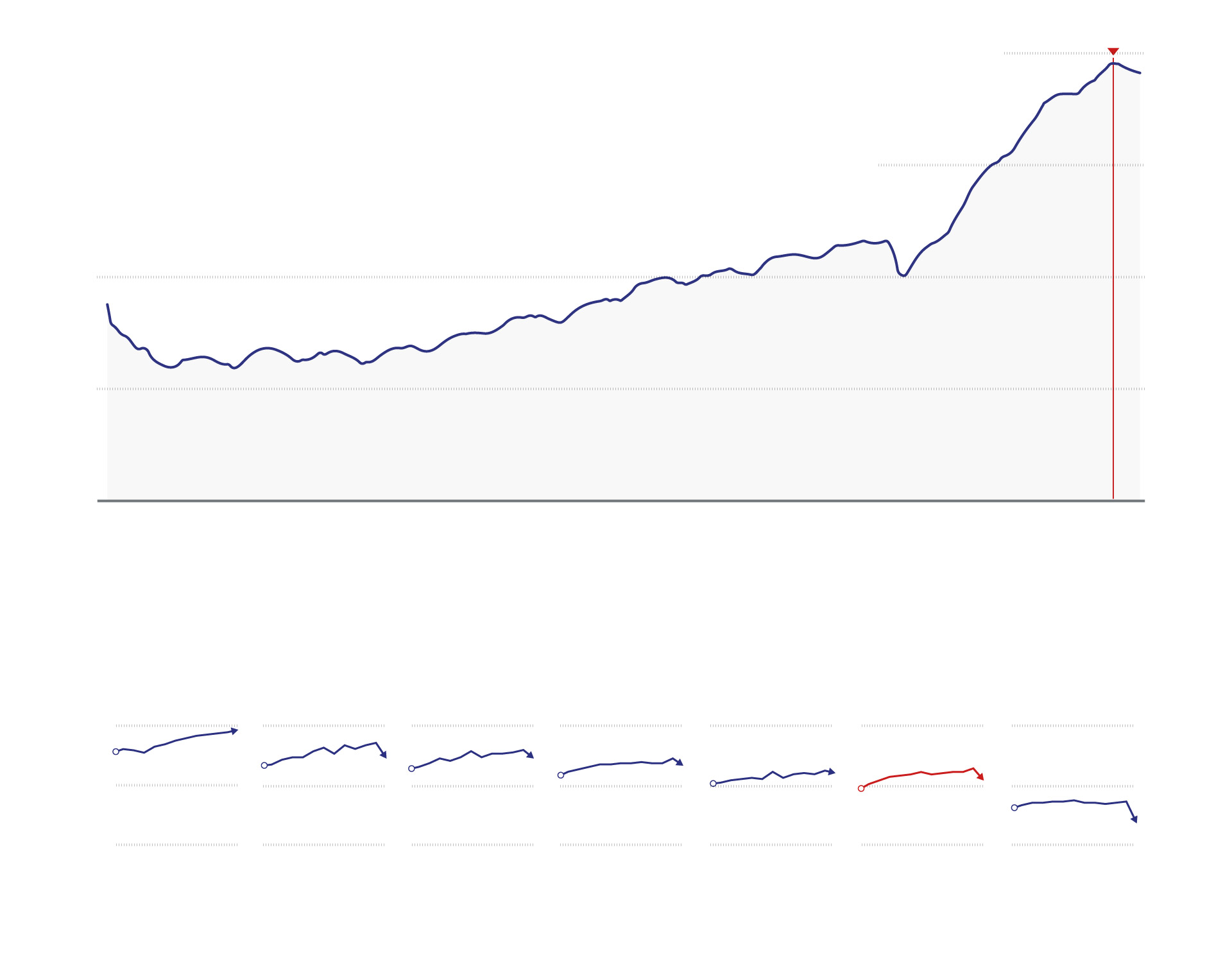

Bristish Consumer Prices Index,

including owner occupiers’ housing costs.

Scottish independence

referendum

What goods and services

costing £100 in 2010

would cost …

Sources: Britain’s Office for National Statistics,

Bank of England

Scottish independence

referendum

British Consumer Price Index, including owner

occupiers’ housing costs.

Scottish independence

referendum

What goods and services

costing £100 in 2010

would cost …

Sources: Britain’s Office for National Statistics, Bank of England

Scottish

independence

referendum

British Consumer Price Index

including owner occupiers’

housing costs

What goods and services

costing £100 in 2010

would cost …

Sources: Britain’s Office for National Statistics, Bank of England

Scottish

independence

referendum

British Consumer Price Index,

including owner occupiers’ housing costs

What goods and services

costing £100 in 2010

would cost …

Sources: Britain’s Office for National Statistics, Bank of England

At the least, it’s been chaotic. Britain has had five prime ministers in 14 years, including one who lasted just 49 days — the briefest government in hundreds of years. The country cycled through nine foreign secretaries and eight home secretaries.

There were four national elections, a vote on Scottish independence that failed and a vote on leaving the European Union that did not — yielding Britain’s exit from the bloc.

But Brexit, approved by voters in 2016 and completed in 2020, was just one seismic shift. The Conservatives took the reins in the aftermath of a global financial crisis, watched as a pandemic hit Britain harder than many of its peers, and responded to a major land war on continental Europe.

To cap it all off? The queen died.

The fallout from these 14 years has been a focal point of Labour’s campaign. Party leader Keir Starmer, likely to become the next prime minister, has pushed for change. But how much of the challenge confronting Britain is the result of bad policies and how much of it was unavoidable?

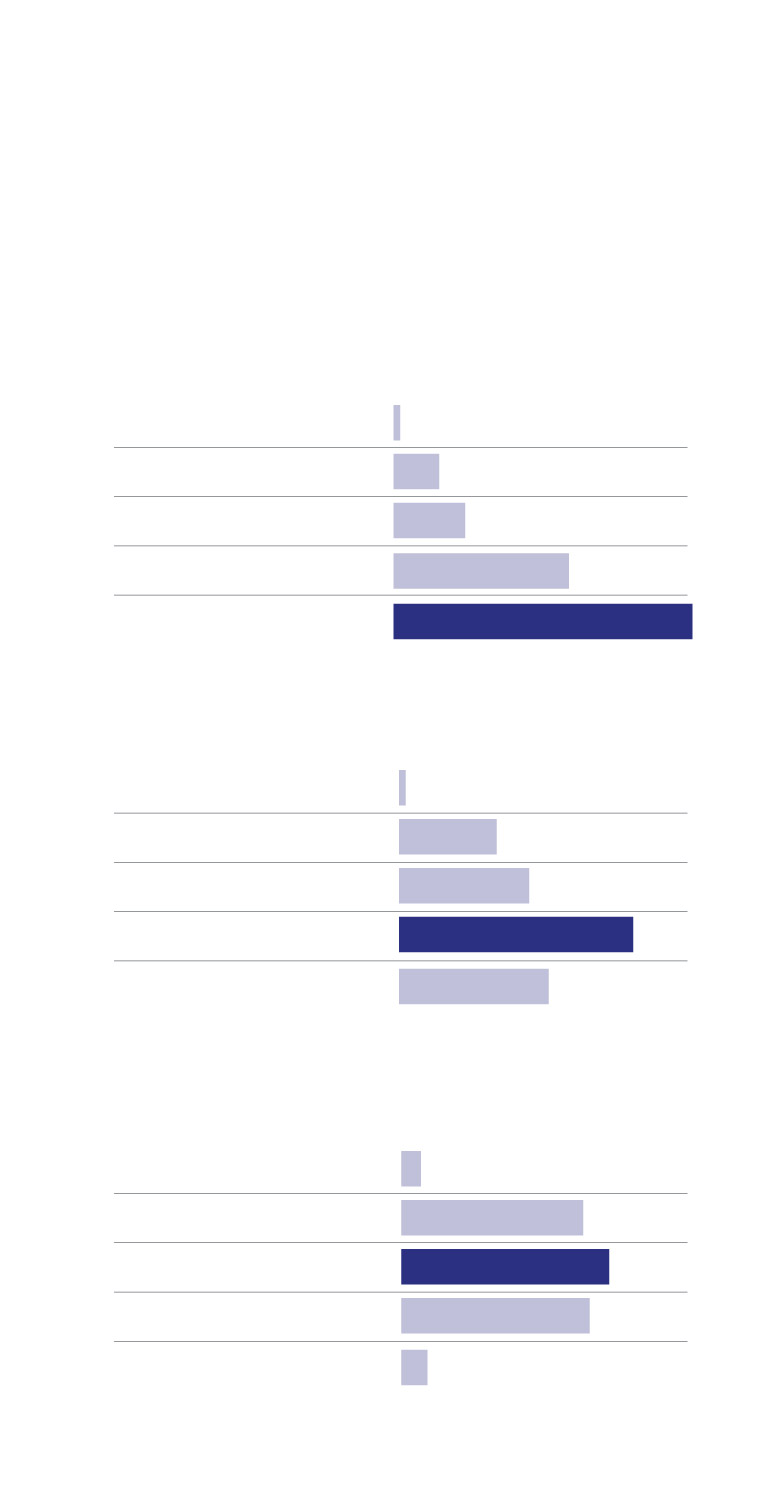

Is Britain in a worse

state than in 2010?

Thinking about the condition of Britain, do you think things are currently better, worse, or about the same as they were when the Conservatives first came to power in 2010?

Voted Conservative in 2019

Intend to vote Conservative

Is Britain in a worse state

than in 2010?

Thinking about the condition of Britain, do you think things are currently better, worse, or about the same as they were when the Conservatives first came to power in 2010?

Voted Conservative in 2019

Intend to vote Conservative

Is Britain in a worse state than in 2010?

Thinking about the condition of Britain, do you think things are currently better, worse, or about the same as they were when the Conservatives first came to power in 2010?

Voted Conservative

in 2019

Intend to vote

Conservative

Is Britain in a worse state than in 2010??

Thinking about the condition of Britain, do you think things are currently better, worse, or about the same as they were when the Conservatives first came to power in 2010?

Voted Conservative

in 2019

Intend to vote

Conservative

It’s funny, but nobody in Britain really wants to talk about Brexit anymore — except Nigel Farage.

In what many now consider a colossal political miscalculation, David Cameron kept Farage and his U.K. Independence Party in the Conservative fold for the 2015 general election by promising a Brexit referendum. His bet was that British voters would want to remain in the European Union. They did not. Within hours of the vote, Cameron announced his resignation. Theresa May’s premiership was consumed by Brexit chaos. Boris Johnson was a Brexit booster. So is Rishi Sunak.

The people generally consider Brexit a flop. But there’s no going back — not quickly.

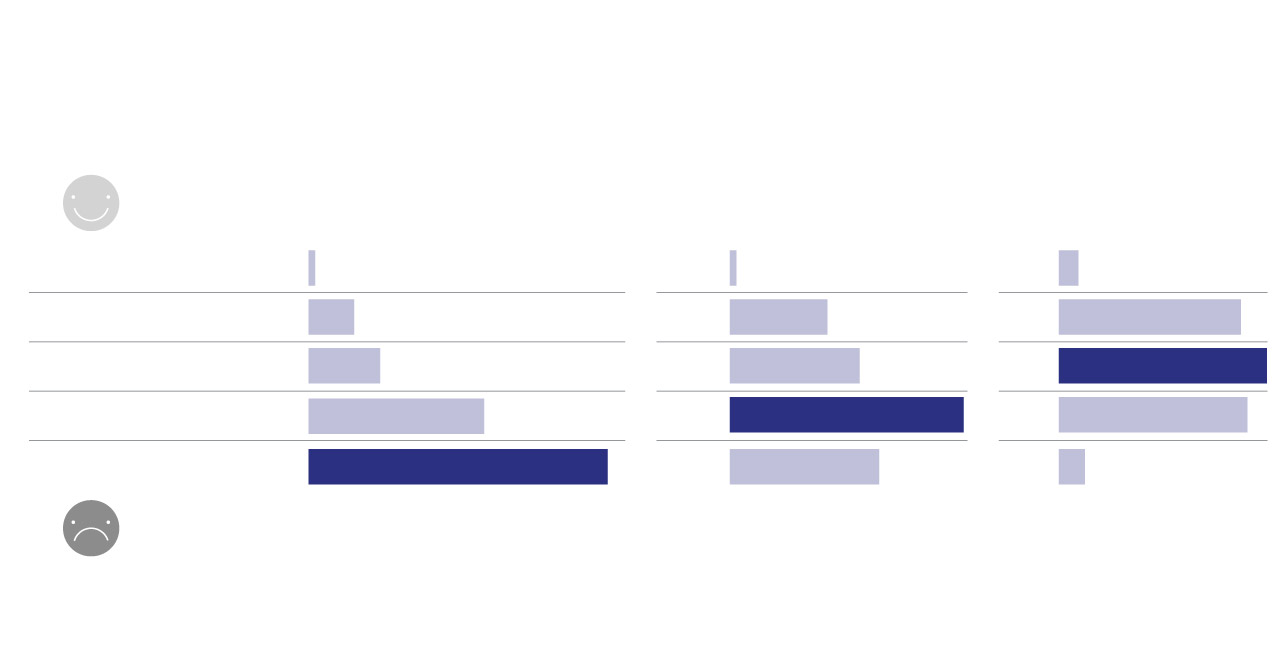

Brexit: Benefits vs. negatives

The benefits

of Brexit have

outweighed

the negatives

The negatives

of Brexit have

outweighed

the benefits

The benefits

and negatives

have balanced

each other out

Brexit: Benefits vs. negatives

The benefits

of Brexit have

outweighed

the negatives

The negatives

of Brexit have

outweighed

the benefits

The benefits

and negatives

have balanced

each other out

Brexit: Benefits vs. negatives

The negatives

of Brexit have

outweighed

the benefits

The benefits

of Brexit have

outweighed

the negatives

The benefits

and negatives

have balanced

each other out

Brexit: Benefits vs. negatives

The negatives

of Brexit have

outweighed

the benefits

The benefits

of Brexit have

outweighed

the negatives

The benefits

and negatives

have balanced

each other out

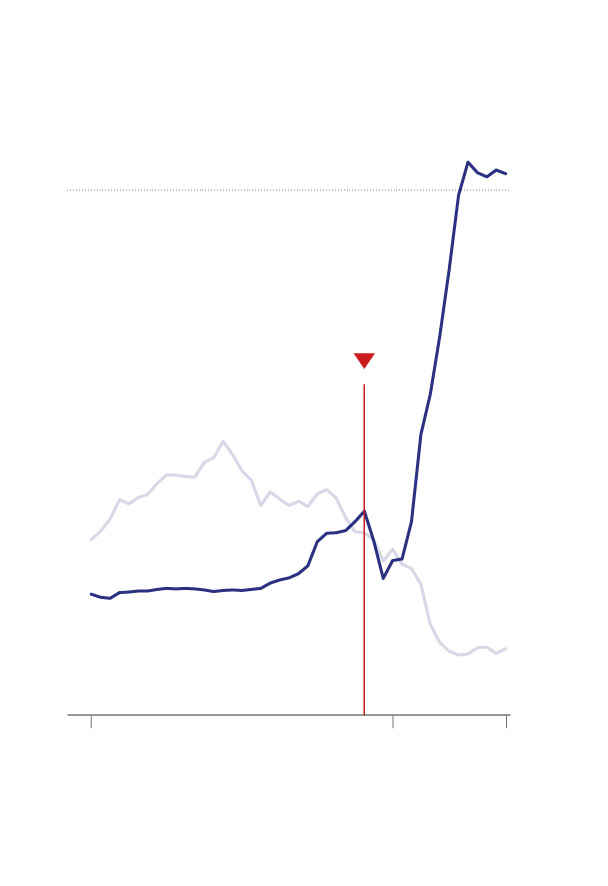

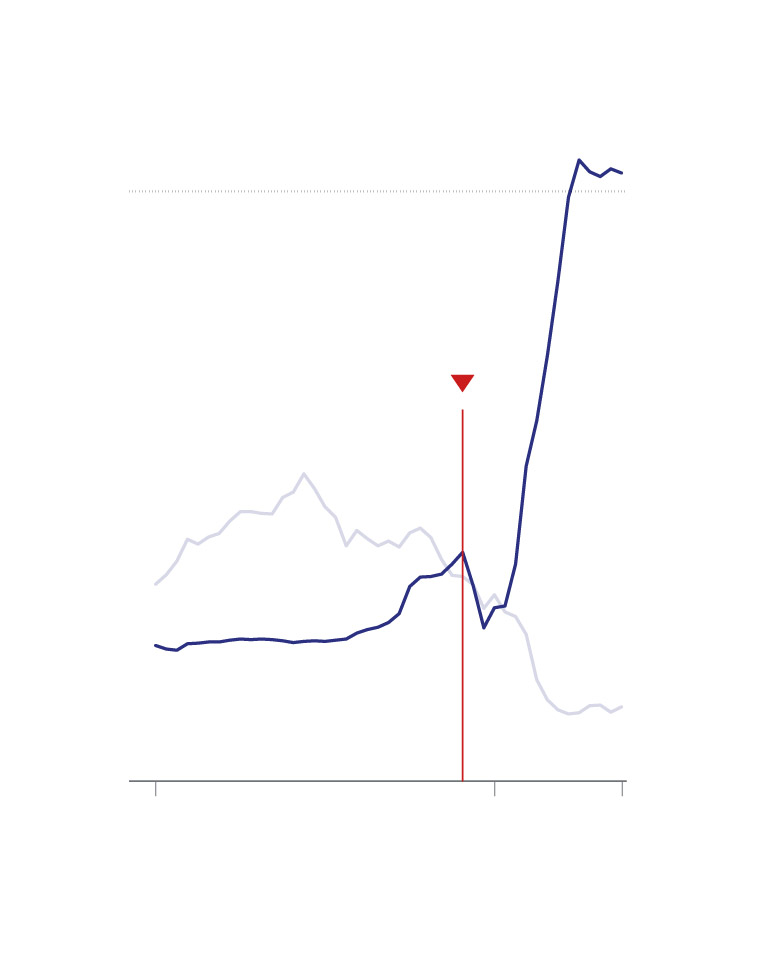

The “Leave” vote was driven in part by fear of immigration. Exiting the E.U. was supposed to give Britain greater control of its borders. In reality, net immigration has soared.

Cameron and May vowed to cap net migration in the “tens of thousands.” Johnson promised the numbers would come down. Sunak said he would “stop the boats” that were illegally crossing the English Channel and send asylum seekers to Rwanda. No flights have left.

Annual net migration has more than doubled since the start of Conservative Party rule. The nationalities have changed. Before Brexit, most long-term migrants came from member states of the European Union. Now, the majority of immigrants come from outside the bloc. The top sources last year were India, Nigeria, China, Pakistan and Zimbabwe.

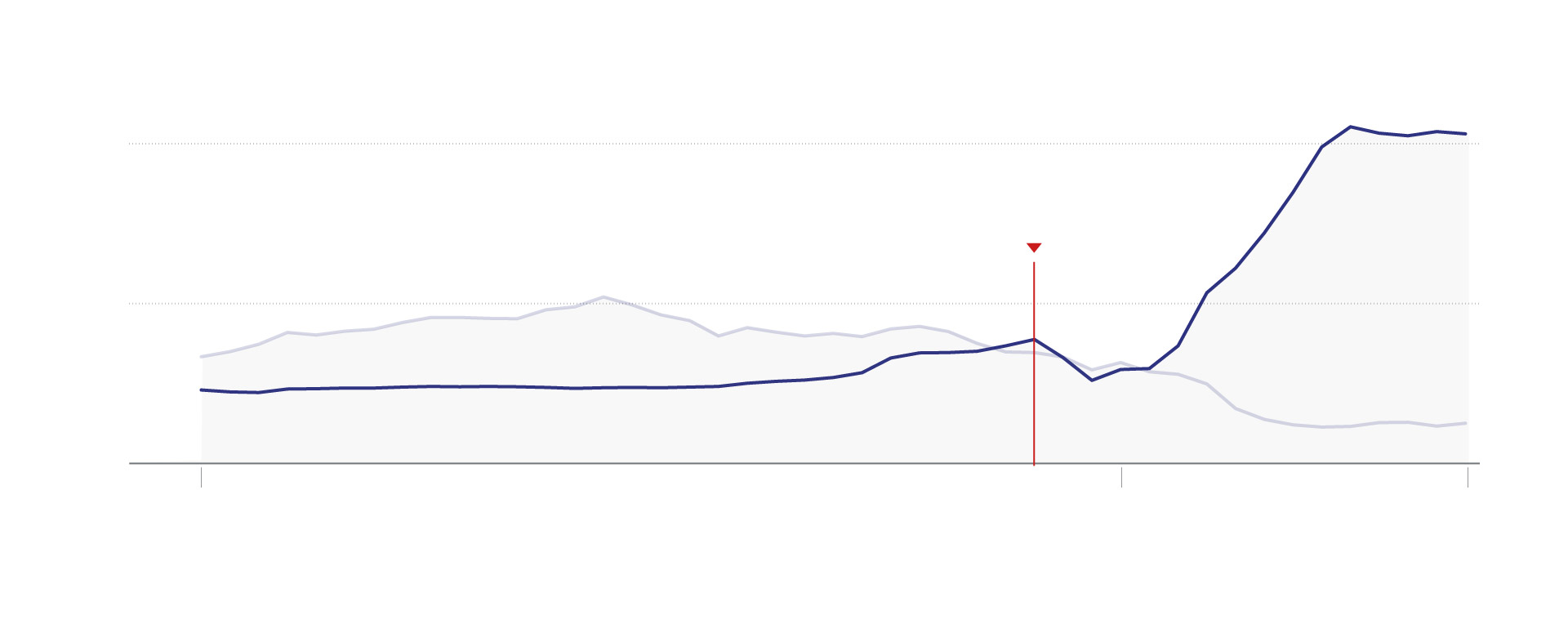

Long-term international

migration to Britain

Source: Britain’s Office for National Statistics

Long-term international

migration to Britain

Source: Britain’s Office for National Statistics

Long-term international migration to Britain

Source: Britain’s Office for National Statistics

Long-term international migration to Britain

Source: Britain’s Office for National Statistics

What’s driving the surge? Policy decisions. The government wants more international students, who pay a premium to study at British universities, and workers to fill low-wage jobs in nursing homes and other fields.

Before Brexit, a different word hung over Conservative policy: “austerity.”

Cameron pushed spending cuts intended to reduce government debt and deficit. The goal was never achieved — public debt this year hit its highest rate as a percentage of economic output since the 1960s — but austerity had many side effects, including huge cuts to local governments that hit services such as schools and swimming pools.

Britain’s beloved National Health Service was one of the few places to see funding rise in real terms during this period, but it mostly failed to match pre-2010 trends, let alone keep up with spiking inflation, immigration and the needs of an aging population. Under the Conservatives, waiting times for treatment have surged.

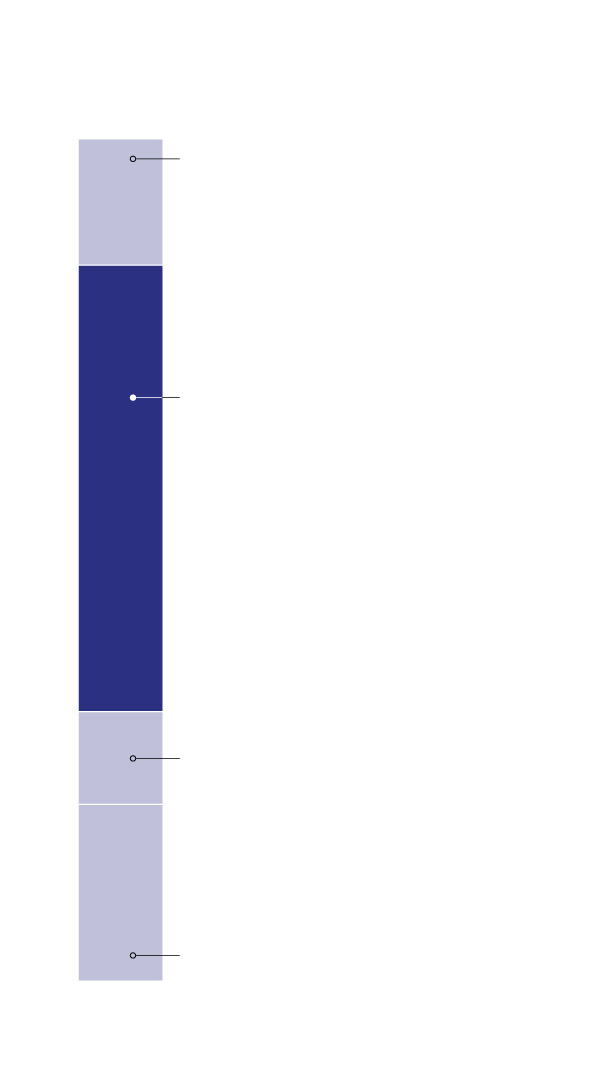

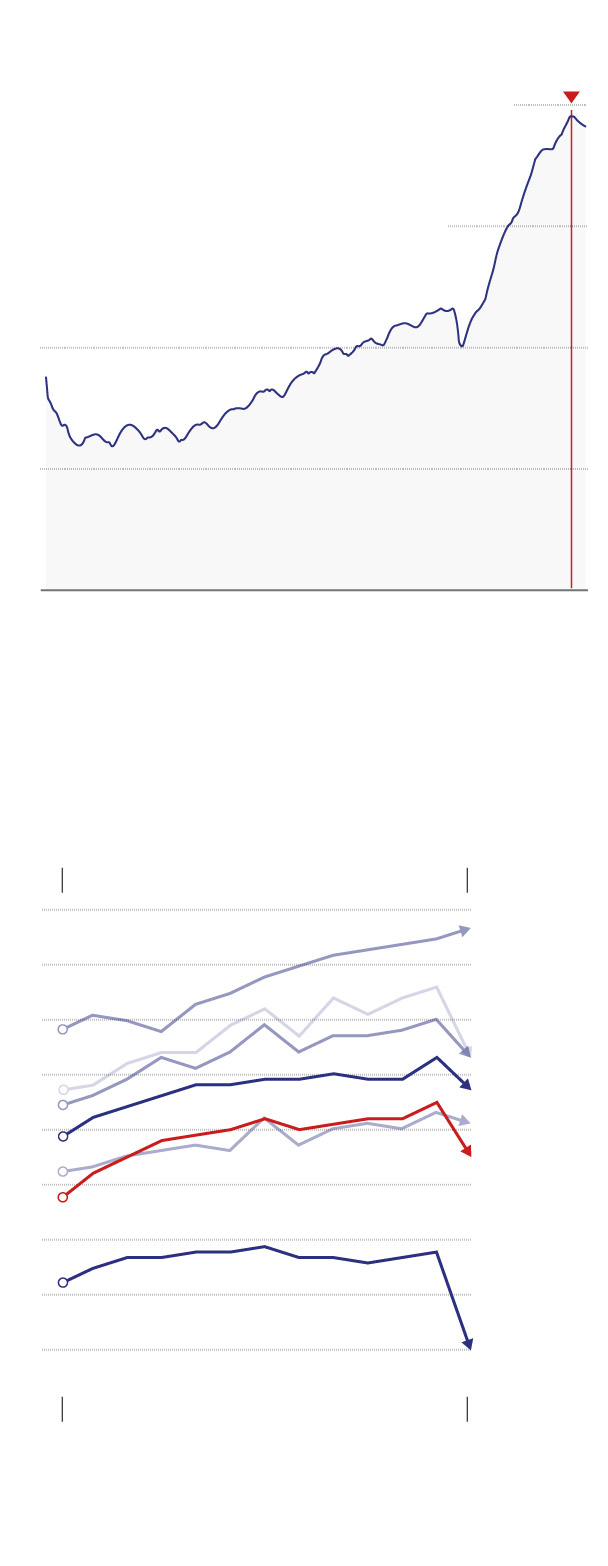

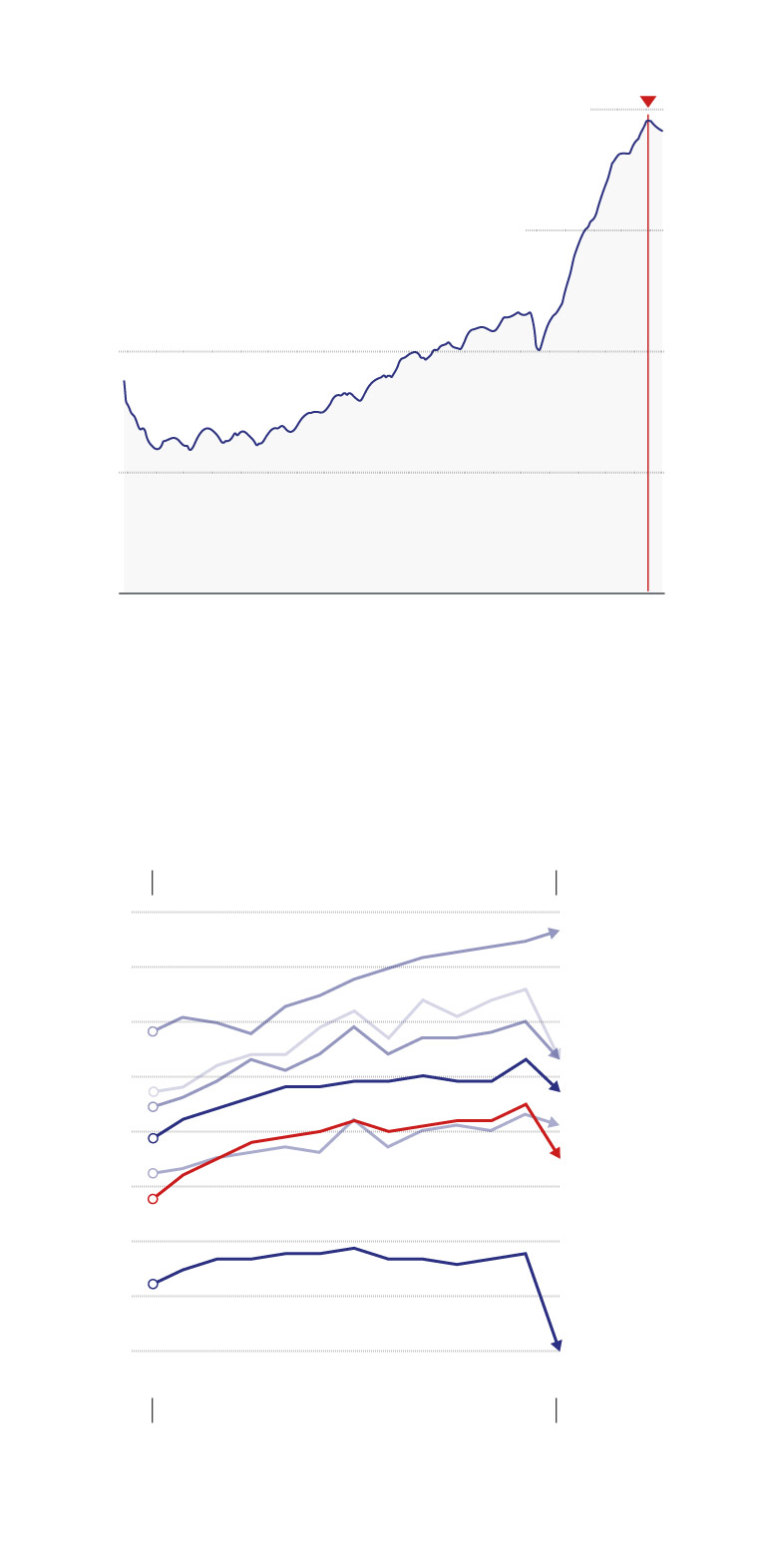

7.8 million

in Sept. 2023

Waiting list for

hospital treatment

Source: Britain’s Office for National Statistics

Source: Organization for Economic

Cooperation and Development

7.8 million

in Sept. 2023

Waiting list for

hospital treatment

Source: Britain’s Office for National Statistics

Source: Organization for Economic

Cooperation and Development

7.8 million

in Sept. 2023

Waiting list for hospital treatment

Source: Britain’s Office for National Statistics

Source: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

7.8 million

in Sept. 2023

Waiting list for hospital treatment

Source: Britain’s Office for National Statistics

Source: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

Britain’s high death rate during the coronavirus pandemic — 20th in the world, according to a data from the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine — has been widely attributed to a troubled public health system.

Life expectancy at birth, a key indicator of a country’s health, has stagnated in Britain since 2010, leaving the country sixth in the Group of Seven highly developed nations, ahead only of the United States, long an outlier in health outcomes.

Researchers at the London School of Economics have blamed austerity. They argue that funding constraints not only on the NHS but also welfare and other public services have cost the British nearly half a year of life expectancy.

Britain remains one of the world’s largest economies, but its rate of growth has fallen well off its pre-2010 trajectory.

The National Institute of Economic and Social Research lays much of the blame on Brexit. By last year, the institute concluded, the departure from the E.U. had already cost the country up to 3 percent of its real gross domestic product, or roughly $1,000 per person.

But a scratch beneath the surface reveals conditions that are still more troubling. Growth in GDP — the country’s total economic output — has been propelled largely by a population boost caused by immigration and demographic shifts.

Growth in productivity, measured by economic output per hour worked across the country, has lagged, placing Britain far lower than many of its peers. The slowdown began around Cameron’s election fourteen years ago.

The Conservative win in 2010 took place just after the global financial crisis shook Britain and many other nations. Some analysts say events for which the government can be blamed, such as Brexit, can’t be disentangled from those it cannot, including the financial crisis, the pandemic and the war in Ukraine.

But whatever the cause, the impacts are real. Wages have remained roughly in line with productivity, resulting in what has been described as the longest period of stagnation in British pay for centuries.

The Conservatives can claim some successes, including keeping educational achievement at a high international standard and taking a leading role in supporting Ukraine against Russian invaders. But if there’s a green shoot to the Tory years, it’s that Britain asserted itself as a world leader in the fight against climate change.

Under May, Britain pledged to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions to “net zero” by 2050. Johnson backed a “green industrial revolution.” But Sunak tapped on the brakes. He delayed by five years a ban on the sale of new gasoline and diesel cars, for example, saying Britain must reduce emissions in a “pragmatic, proportionate and realistic way.”

Meanwhile, the use of green energy has exploded. In 2023, renewables — notably, wind, solar, biomass and hydro power — generated 47 percent of the country’s electricity.

It’s an outcome that belies the political chaos of the period — in 14 years, Britain had 10 environment secretaries.

Discussion about this post