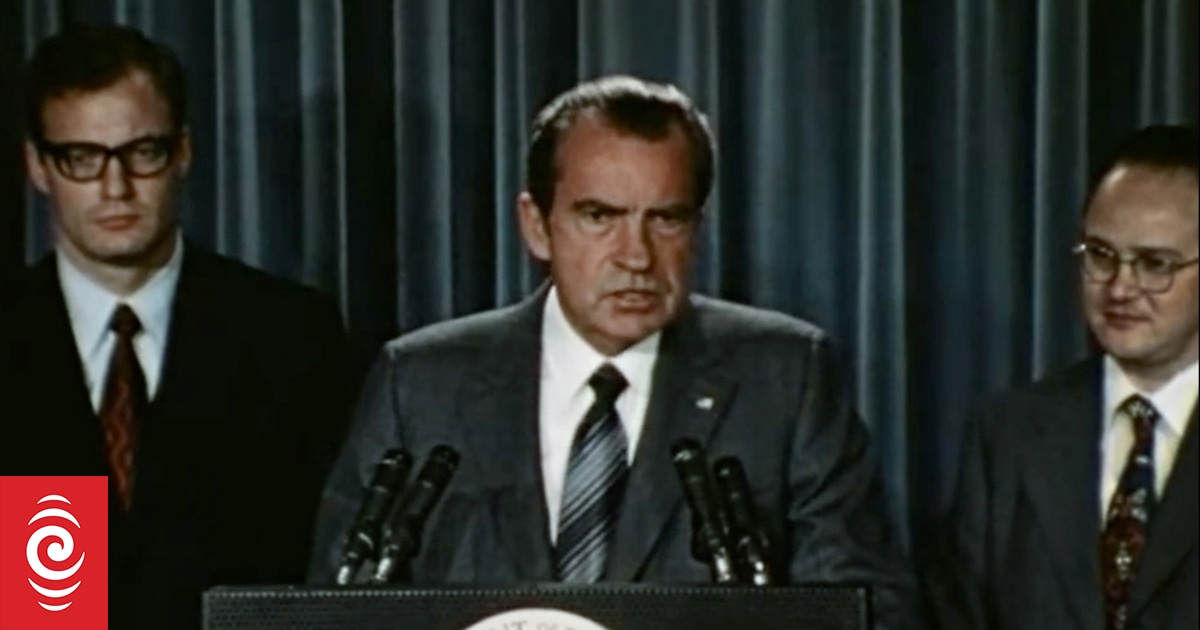

It’s half a century since the War on Drugs was declared. New Zealand was an enthusiastic ally of then-US President Richard Nixon in the battle. A new documentary from RNZ – Guyon Espiner: Wasted – investigates the costs of continuing the fight.

When the 79-year-old President of America, where the War on Drugs began, pardons thousands of people for the crime of possessing marijuana you can smell that change is in the air.

When the Economist, a sober, rigorous adherent to economic liberalism, says that Joe Biden is being too timid and it’s time to legalise cocaine, you get a sense of how far-reaching that change might be.

When you consider New Zealand, which sees itself as a socially liberal democracy, still maintains a prohibition on cannabis and locks people up just for possessing drugs, you realise how far we are falling behind.

President Richard Nixon, who later resigned after the Watergate scandal, launched the War on Drugs in 1971, declaring “America’s public enemy No 1” was drug abuse and vowing to “wage a new, all out offensive”.

New Zealand joined the war effort a few years later and our legislation to combat drug harm is still anchored in that era with the Misuse of Drugs Act 1975.

“New Zealanders might be a little bit disturbed to think we have Richard Nixon’s legislation in place to govern our drug policy today,” Drug Foundation executive director Sarah Helm says in the new RNZ documentary Guyon Espiner: Wasted.

WATCH THE DOCUMENTARY

Guyon Espiner: Wasted premiered on RNZ and TVNZ1 on Wednesday night. You can watch it on demand any time by clicking here.

In a world still reeling from the Covid-19 pandemic, and askew with disinformation, we are urged to follow the facts and the science. It’s instructive to take that advice and overlay it on our approach to drug harm.

“We’ve legislated certain types of drugs in certain ways because of history and prejudice, not because of science and evidence,” Tim McKinnel, a former drug squad detective, says in the documentary, which also tracks his path from kicking in the doors of tinny houses to concluding that all drugs should be decriminalised.

McKinnel, who did a masters degree in criminology, is alluding here to the dark roots of the War on Drugs, which sprouted in the fertile ground of racism and moral panic.

The chief architect was Harry Anslinger, who served five US presidents over 32 years as chief of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics.

Anslinger was an adept propagandist and used what he called ‘the gore files’ to spread fear about drugs in the popular press.

The 1937 film Reefer Madness picked up one of his most lurid tales, where he claimed that a “quiet young man” murdered his entire family while “pitifully crazed” on marijuana (it later emerged the man was mentally ill).

Anslinger’s claims of despicable crimes committed while under the influence of drugs were often racially charged, and chief among his targets were African American jazz musicians.

The history is neatly outlined in British journalist Johann Hari’s book Chasing the Scream (2015) and the movie The United States vs. Billie Holiday (2021) is based on Hari’s book.

Private Investigator Tim McKinnel

Photo: RNZ / Cole Eastham-Farrelly

In the Wasted documentary McKinnel and others point out how far New Zealand lawmakers have diverged from the science in their approach to combating drug harm.

International studies – most famously Professor David Nutt’s 2010 study – have shown that alcohol is the drug that causes the most harm to the individual and to the community.

The drugs that do the least harm both to the user and to society, psychedelics like LSD and mushrooms, are Class A drugs in New Zealand, attracting a life sentence for supply and six months in jail for possession.

In 2016, the Drug Harm Index estimated that New Zealand spends about $350 million dollars a year on drug interventions.

Of that, $170 million was spent on courts and prisons, $100 million went on policing and just $80 million was allocated for health care.

New Zealand still locks people up just for taking drugs. In 2021, about 3100 people were convicted for low level drug crimes like possession and personal use. Of those, about half were Māori.

In the last ten years, 35,000 New Zealanders have been convicted of a cannabis offence and 5500 have been sent to prison.

New Zealand came close to major drug reform in 2020 but the referendum to legalise cannabis narrowly failed.

Portugal decriminalised all drugs more than 20 years ago now and the model has spread to other countries including Canada and parts of America and Australia.

New Zealand doesn’t usually look to Australia for progressive social reform but the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) has moved well ahead of us.

In Canberra, it is legal to smoke cannabis at home and to grow up to four cannabis plants per household or possess up to 50 grams of cannabis.

In Wasted, Health Minister Rachel Stephen-Smith outlines how the ACT plans to expand the policy to include 11 of the most commonly used drugs.

If users are caught with small amounts of these drugs – including MDMA, LSD, psilocybin (magic mushrooms), heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamine – they would get a $100 fine rather than jail time.

Possession of these drugs would cease to be a criminal matter, Stephen-Smith says.

“We know that one of the significant harms associated with illicit drug use, as well as the health harms, is the criminalisation of people and that comes from being engaged in the criminal justice system, but also the stigma associated with that and the reluctance to seek treatment and seek support.”

There are pockets of New Zealand where a health approach is being used. The law was changed in 2021 to allow people to have their drugs tested, and checking stations have popped up in the major centres and at music festivals.

This is the harm reduction approach at work: the idea that some people are always going to take drugs so it’s better they have a big party night out rather than kill themselves taking a mystery, or contaminated, substance.

But largely New Zealand is still fighting the War on Drugs. Wasted asks: is that a waste of time, money and lives.

Discussion about this post