When the federal Covid-19 public health emergency ends on May 11, it will be the end of an era for the American health system.

For more than three years, in a nation where patients usually pay more for health care than residents of any other high-income country, tests and vaccines were available to all Americans for free. Treatment was free for many people, too, including those without insurance.

Health care providers adapted on the fly, moving services to the computer or the phone in order to continue treating patients. Hospitals got an important infusion of government funding at a time when, at least at first, they were forced to cancel many of their surgeries and other services in order to handle surges of patients as the coronavirus spread.

But the Biden administration announced Monday that the public health emergency will end in May, which will stop some of those provisions. Others, extended by Congress recently, will have a limited life span unless lawmakers decide to act again.

American health care is, like everything else, getting back to normal — which means it will be harder for some people to access the health care they need.

“As we transition into the new normal, we are returning mostly to our fragmented health system as we knew it,” Jen Kates, director of global health at the Kaiser Family Foundation, which has analyzed the implications of the emergency’s end, told me.

The most important pandemic provision that will start to wind down in the next few months is Medicaid’s policy of continuous coverage. Usually, states regularly check whether people enrolled in Medicaid are still eligible for it. But with additional federal funding, states kept everyone on the rolls throughout the pandemic. Those checks will resume over the course of this year, and millions of people are expected to lose their health coverage — whether or not they should.

The resumption of enrollment verification is not directly tied to the end of the public health emergency that the Biden administration announced this week. Nevertheless, the looming end of a number of policies put in place for the pandemic will affect millions more. Here are a few worth knowing about.

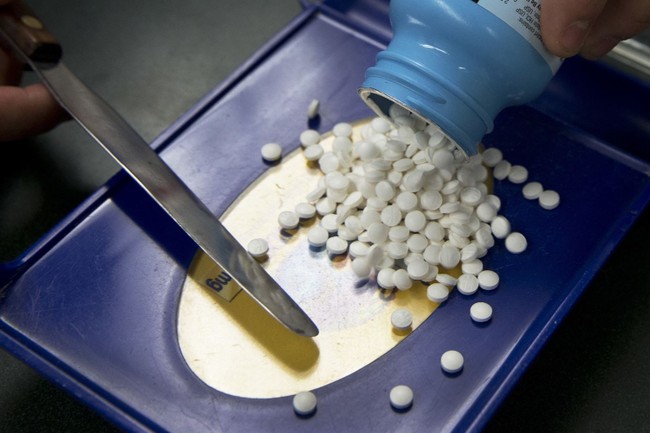

1) People aren’t going to get free at-home Covid tests in the mail anymore — and that’s not the only thing

The pandemic has been, in some ways, a unique experiment in universal health care for America. Though the rules have evolved over time, at one point or another, Covid-19 tests, vaccines, and treatment have been available to everyone for free. As of right now, you can still order free at-home tests from the federal government. Even those without insurance can get their shots or an antiviral at no charge.

That will start to change with the end of the public health emergency, though how much people have to pay and for what will depend on their insurer. For people without insurance, still about 8 percent of the population, they will now face the full cost if they want to get a test or if they need medication after contracting the coronavirus.

People with health coverage could also face some additional costs. People with private insurance, about half of the population, could already be on the hook for out-of-pocket costs for antivirals, but tests and vaccines have been free. That could change now, depending on your individual health plan. Medicare beneficiaries will no longer receive at-home tests for free, either.

Medicaid enrollees will continue to get free tests and treatment for another year, though they can face some cost-sharing responsibility after that. Vaccines remain free, as the program is required to cover all recommended vaccines at zero cost to the patient.

2) The clock is now ticking on coverage for telehealth services and even Covid-19 antivirals

The partial economic shutdown of 2020 has led to a proliferation of online and phone services offered by health care providers and the willingness of insurers, including government programs, to cover them. It has made a vital difference: According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, 40 percent of visits related to mental health and substance use disorders were conducted virtually during the height of the pandemic.

The end of the public health emergency would have brought an end to the expanded access to telehealth that Medicare and Medicaid had authorized during the pandemic. But Congress postponed that expiration date for Medicare until the end of 2024 in the end-of-year spending package. For Medicaid, it will vary depending on the state: Most states say they plan to make permanent some of the looser geographic restrictions and other policy changes they’d adopted during the pandemic, but beneficiaries may lose access to some services they currently have.

Medicare was also set to lose its authority to cover drugs approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for emergency use during a public health emergency, such as the current Covid-19 antivirals, but Congress also intervened there and put off the end of that provision until the end of 2024. States will make their own decisions about Medicaid coverage.

Pfizer applied for full FDA approval last June, which would render this issue moot. The FDA was still, as of December, reviewing the application.

3) Hospitals are about to lose more of their emergency Covid funding

The story of how the pandemic affected hospitals is complicated. Major systems were better positioned to weather difficult fiscal times, like when they canceled elective surgeries in the early weeks of the pandemic. They have also availed themselves of the emergency funding that Congress approved even if they did not necessarily need it, as the Wall Street Journal documented in a recent investigation.

But smaller hospitals already operate with thinner financial margins, many of them unprofitable and already reliant on government funding to stay afloat. The pandemic had brought some additional revenue streams, including a provision tied to the public health emergency that gave them a 20 percent pay bump for every Covid-19 discharge. But that will expire with the emergency’s end.

These hospitals already lost other sources of pandemic funding at the beginning of last year. What followed was one of the worst stretches of the pandemic, some of the leaders at these facilities say, because they could no longer afford to hire additional staff to handle the flood of patients.

As small community hospitals struggle to retain services and staff given their fiscally precarious position, this additional loss of revenue is likely to make their situation only more difficult.

Discussion about this post