New

Zealand’s second Omicron wave might just be easing up,

with the latest data showing we seem to be in a downward

trend. So are those who never got Covid-19 now in the

minority?

The SMC asked experts about what the latest

data say about rates of infection, what we still don’t

know, and how this affects wider immunity to the

virus.

Professor Michael Plank, Te Pūnaha Matatini

and University of Canterbury, comments:

What do the

data tell you about how many New Zealanders have or

haven’t been infected?

“The true number of people

who’ve had Covid-19 is unknown because we only know about

cases who get tested and report their result. The proportion

of infections that are reported is probably somewhere

between 40% and 65%. It’s unlikely to be much less than

40% because at least 40% of all 20-25 year olds have already

reported a case. On the other hand the reported infection

rate is typically less than 65% of the infection rate in

routinely tested cohorts such as border workers. This means

it’s likely that at least half of New Zealanders have had

Covid-19, although those that haven’t probably still

represent a significant minority.”

What does this

mean for our herd immunity to Covid?

“The lack of

an accurate estimate for the true number of infections

creates uncertainty about how much immunity there currently

is in the population. This makes it harder to estimate the

potential size of future waves of Covid-19 or the impact of

new variants. The best way to get an accurate picture of the

true number of infections would be to systematically test a

representative sample of the population on a regular basis.

This would provide high-quality ongoing data about the level

of Covid-19 in the community and reduce our reliance on

self-reported test results.”

Conflict of interest

statement: “Michael Plank is funded by the Department of

Prime Minister and Cabinet for mathematical modelling of

Covid-19.”

Professor Mike Bunce, Principal

Scientist (Genomics), Institute of Environmental Science and

Research, comments:

What do the data tell you about

how many New Zealanders have or haven’t been

infected?

“Last week the official tally of

registered cases in Aotearoa New Zealand was approximately

1.62 million people. We know that this number is under the

true number of infections due to asymptomatic cases,

non-reporting of positive cases, reinfections and

failure/unwillingness to test (even if unwell). The Ministry

of Health is planning a prevalence survey that will be key

in ascertaining the true number of infections, as a

person’s antibody profile can tell us if a person has been

previously exposed to the virus (as opposed to the vaccine).

In the UK, this approach showed that >95% of the

population has been exposed to SARS-CoV-2 in the pandemic,

many of these are recent infections. Looking at one cohort,

primary school students, in November 2021 approximately 40%

(pre Omicron) of students had been exposed. In March of 2022

this number was >80%.

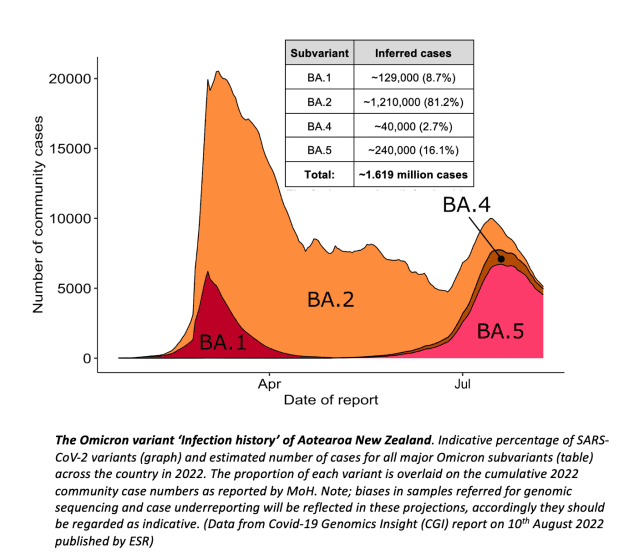

“What we do know from our

genomic surveillance here in Aotearoa is the approximate

proportions of each of the variants (see figure and embedded

table). This temporal infection history is important as the

variants of SARS-CoV-2 that we are exposed to (coupled with

vaccines and time since infection) are key factor in

determining the traction new forms of SARS-CoV-2 will have.

For example, the reason that the BA.5 wave here in New

Zealand was at the lower end of the modelling predictions

could be because our population was heavily exposed to the

BA.2 variant of Omicron which is closer to BA.5 than

original BA.1.

credit: ESR

What do we still

not know? What data do we still need?

“The serology

survey (soon to be conducted) and modelling of this data in

concert with hospitalisation rates and wastewater will

likely provide a more nuanced picture of the total number of

Kiwis that have been exposed to Covid-19 – but working out

the ‘true’ number of infected (and reinfected) people

will always remain a challenge. High rates of participation

in initiatives like FluTracker may also facilitate better

estimates of symptomatic infections across the Motu. There

are aspirations here at ESR to better characterise the

(often seasonal) viruses that sweep Aotearoa using the

genomic toolkit that we have developed during the pandemic.

For example, PCR testing (or genomics) that can distinguish

RSV, flu, Covid-19 or other viruses that give us ‘colds’

can be used to better understand the exact virus that is

driving illness, and what strain of each virus is

present.

What does this mean for our herd immunity to

Covid?

“Determining how susceptible/resilient a

population is to new wave of Covid-19 is a complex interplay

of; (i) vaccine and booster rates (ii) percentage of the

population with protective immunity (iii) time since

infection/vaccines (iv) new variants of SARS-CoV-2 that

might escape prior immunity (v) Mask use and other social

factors such as staying at home while sick (vi) the efficacy

of pharmaceuticals to treat Covid-19 patients and reduce

viral loads and, (vii) the development of new vaccines that

might reduce/prevent infections.

“Taken together,

this shopping list of factors paints a picture of why it is

difficult to predict how protected or vulnerable New

Zealanders might be. While we would like to be more certain

what the virus’s next move might be, history has taught us

that diseases are adept at changing the ‘playing field’

and as we adapt our strategies we nudge the virus in

different directions. So while we may well estimate a level

of ‘herd immunity’ that might be protective one week, it

may change the next. Predicting the trajectory of ‘new’

RNA viruses such as SARS-CoV-2 adds another layer of

difficulty as they continue to rapidly explore different

ways to gain a fitness advantage in a new

host.”

Conflict of interest statement: “ESR

receives funding from the Ministry of Health to process

clinical samples for whole genome sequencing and

wastewater.”

Dr Dion O’Neale, Project Lead,

COVID Modelling Aotearoa; and Senior Lecturer, Physics

Department, University of Auckland, comments:

What do

the data tell you about how many New Zealanders have or

haven’t been infected?

“Data from the Ministry of

Health records just under 1.7 million confirmed cases of

COVID-19 in Aotearoa New Zealand. Of these, just over 28,000

cases are recorded as probable reinfections in people who

have been a confirmed case of COVID-19 twice or more. Both

the number of confirmed cases and the number of recorded

reinfections will be a significant under-estimate of the

true number of infections. This is because not all

infections end up being recorded as a case.

“The

ratio of the number of infections in the community to the

number of confirmed cases that we know about is called the

case ascertainment rate, or CAR. This rate will typically

change over time, depending on a number of factors such as

how easy it is for people to access tests and how inclined

they are to seek a test and to report the result. Most

estimates of the CAR put it above 33% but probably below

50%. If we ignore reinfections this means that the number of

infections that we have had in Aotearoa is (at least)

roughly twice the number of confirmed cases — so over 3

million.

“The effect of the case ascertainment rate

on estimates of the number of reinfections is a little more

complicated. This is because the CAR applies for both the

first infection and for later infections. If someone’s

infection was not recorded as a confirmed case the first

time around then – even if their second infection was

recorded as a confirmed case – it will not be captured as

a reinfection and we will be underestimating the number of

reinfections, or possibly overestimating the number of

unique people who have been infected. This can matter for

disease modelling as the immunity history (the combination

of past vaccinations and infections) of people affects what

the landscape looks like for how susceptible the population

might be for future infections, including with any new

variants.

“Under-reporting of infections can happen

for a number of different reasons; some people may have

confirmed their infection with a rapid antigen test, but not

reported the result; some people may have been symptomatic

and not wanted to use a RAT to confirm their infection, or

may have had a false negative on their RAT due to test

timing or technique; and a sizable number of people may have

not even had symptoms to alert them that they might need to

test for an infection. Estimates are that as many as 40% of

infections may be asymptomatic. Unless these people know

that they have been in contact with a confirmed case – for

example, a family member who has tested positive – or

unless they are testing independently of symptoms, these

people may never have had a reason to test during their

infection.

“Methods like wastewater sampling (e.g.

see the ESR

dashboard) can help us to better understand patterns in

infections and cases, based on how much RNA from SARS-CoV-2

is detected in wastewater, but such methods can be tricky to

calibrate. And while wastewater methods can be useful for

indicating when the case ascertainment rate in a region

might be changing (i.e., if the amount of detected

SARS-CoV-2 RNA is going up but the number of confirmed cases

is not, then case ascertainment is probably getting worse),

it is more difficult for it to tell us what the estimated

number of total infections behind that signal might

be.

“One of the best ways to get a good estimate of

the true number of infections in the community is through

what is called an infection prevalence survey. This includes

methods like that taken by the ONS

in the UK. An infection prevalence survey uses regular

samples from sub-set of the population to calculate the

prevalence of COVID-19 in the community over time and

accounting for differences in location and

population.

“In Aotearoa, the Ministry of Health

announced in July that they would be starting such and

infection prevalence survey. Once underway, this will give

extremely useful information about infections in the

community and how they are distributed. Infection prevalence

surveys give an indication of current infections. They are

often combined with something called a sero-prevalence

survey. Rather than looking for indication of RNA or protein

from a current COVID-19 infection, sero-prevalence surveys

look for the presence of COVID-19 antibodies from past

infection. While antibody markers do fade over time,

seroprevalence surveys can help to give us a view back to

past infections, even when people have now

recovered.

“Information from this sort of survey is

useful in figuring out how much protection from past

infection communities are likely to have and what the

susceptibility landscape looks like for the population in

Aotearoa.”

Conflict of interest statement: “I,

along with others from COVID Modelling Aotearoa, am funded

by the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet to provide

advice on the COVID response and from a Health Research

Council grant to look at equity related to COVID in

Aotearoa.”

© Scoop Media

Discussion about this post