Susan Bushnell was in a hurry when a man, clipboard in hand, approached her outside a Walmart Supercenter in Vista, Calif., one afternoon last September.

The man asked Bushnell to sign a petition as she wrangled her fussing 5-year-old daughter into a shopping cart. He said the petition would help to raise wages for fast-food workers in California.

“Oh, that’s a good cause,” Bushnell remembers thinking, having once worked in retail. Bushnell paused her rush into the San Diego County store to jot down her signature.

But what the man told Bushnell was false. The petition was part of an effort to kill a newly approved law that could bring significant wage increases for California’s fast-food workers.

That law, known as Assembly Bill 257, or the Fast Recovery Act, was set to go into effect Jan. 1 but is now on hold. State election officials said last week that a coalition of fast-food corporations and industry trade groups, which raised millions to oppose the law, had secured enough valid signatures to block implementation of AB 257 until California voters decide next year whether to repeal the law.

Bushnell is among 14 voters interviewed by The Times who say petition circulators for the ballot measure to overturn AB 257 lied to them about what they were signing. Others said the signature gatherers made vague and misleading claims — a Hollywood canvasser, for instance, presented the petition as an inflation cure — or tried to hide legally required paperwork explaining the proposed referendum, sometimes becoming abusive when questioned.

These interactions spanned the state, with examples in Pasadena, Marina del Rey, Westwood, Northridge, Simi Valley, Richmond, Oakland, Hayward and San Francisco. One canvasser sought signatures at a Tijuana school, where he was seen falsifying addresses for signers who weren’t California voters.

“I feel duped,” said Bushnell, who did not realize her mistake until more than a month later when she read a Times report that California’s largest union had filed a complaint with state officials alleging that the industry coalition was “willfully misleading voters.” In support, the union submitted video footage of four interactions in which petition circulators falsely told union organizers that the petition sought to raise worker pay.

Encounters described to The Times offer a glimpse at the haphazard and largely unregulated operation of collecting signatures for statewide voter initiatives. Numerous social media posts called out similar incidents, suggesting The Times’ findings probably represent just a fraction of voters affected by deceptive signature gathering tactics for the AB 257 referendum.

The system can at times incentivize paid circulators to peddle exaggerations or falsehoods in exchange for signatures.

Voter signatures are precious, as industries with deep pockets increasingly turn to the ballot to delay or scuttle legislation they see as a potential hit to their bottom lines.

UC Berkeley English professor Scott Saul said a circulator outside a Safeway in Oakland told him that the petition aimed to guarantee a living wage for fast-food workers. Then, Saul said, the person refused to let him read the official title and summary of the petition, which state authorities require to be visible and accessible, unless he signed the petition first.

“It really got my blood pressure up,” Saul said.

Two signature gatherers set up shop outside a Safeway in Oakland peddling petitions aiming to overturn California laws AB 257 and SB 1137, which boost protections for fast-food workers and ban new oil and gas operations close to where people live and work, respectively.

(Courtesy of Rocky Fernandez)

On Saturday trips to Oakland’s Grand Lake Farmers Market during fall, Emily Pothast said she and her partner regularly encountered paid signature gatherers telling passersby that the referendum would increase worker wages. Pothast said she would correct circulators and tell them to read the petition language more closely.

During one such discussion in October, a woman who appeared to be a supervisor rushed over, started yelling and threatened to call police, Pothast said.

“I was very alarmed,” she said.

The group opposing AB 257, called Save Local Restaurants, told The Times in a statement that it “has been vigilant in maintaining compliance with California’s election laws.”

The coalition did not respond to questions about specific interactions in which petition circulators appeared to flout election rules.

The group had dismissed the allegations lodged in October by Service Employees International Union California — the union that sponsored AB 257 — as “frivolous.”

AB 257, signed by Gov. Gavin Newsom on Labor Day, would create a first-of-its-kind council with broad authority to set standards for fast-food workers’ wages, hours and workplace conditions. The council would have had the ability to raise the minimum wage for fast-food workers as high as $22 in 2023.

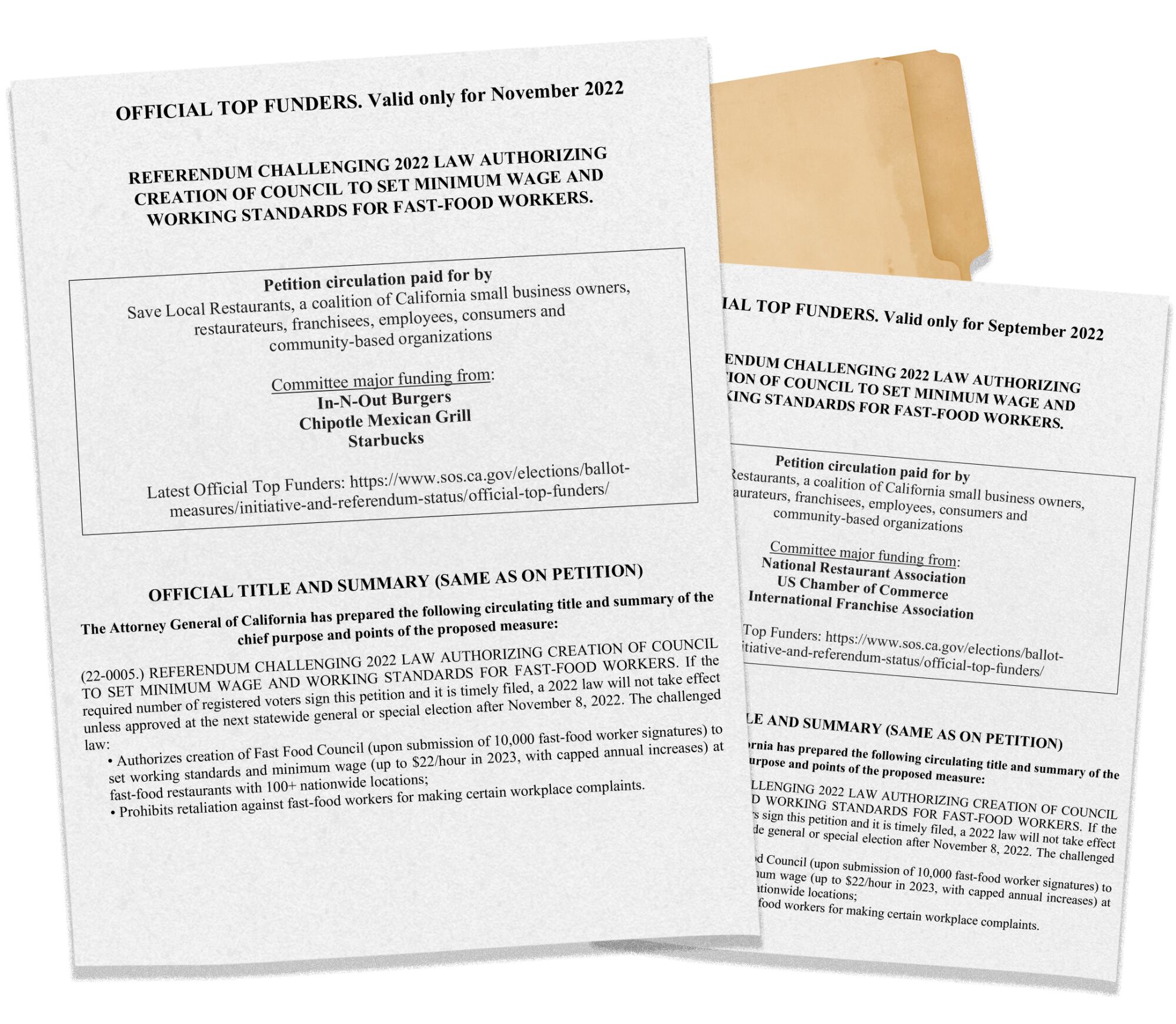

Opponents argued that the law would unfairly burden restaurants with higher labor costs and increase food prices. Fast-food corporations and business trade groups, including In-N-Out, Chipotle, Chick-fil-A, McDonald’s, Starbucks and the National Restaurant Assn., contributed more than $13.7 million to support the referendum as of December, according to California’s nonpartisan Fair Political Practices Commission.

Reports of circulators illegally misrepresenting an issue to voters to collect signatures have surfaced in other statewide referendum efforts, including an oil industry-backed push to block California’s Senate Bill 1137, which banned new oil and gas wells near homes, schools and hospitals.

Petition signatures collected by the oil and gas group are going through a verification process, and the measure is expected to qualify for the ballot.

Petition circulators are “basically hired guns” in expensive statewide campaigns, and the time, resources and stakes involved are “second only to the U.S. presidential election,” said David McCuan, a political science professor at Sonoma State.

For many ballot initiative campaigns, McCuan said, defending against allegations that circulators exaggerated or lied is seen merely as the cost of doing business. State election rules are “not a deterrent by any stretch of the imagination,” and “the tales for what the measure purports to do can become quite tall,” he said.

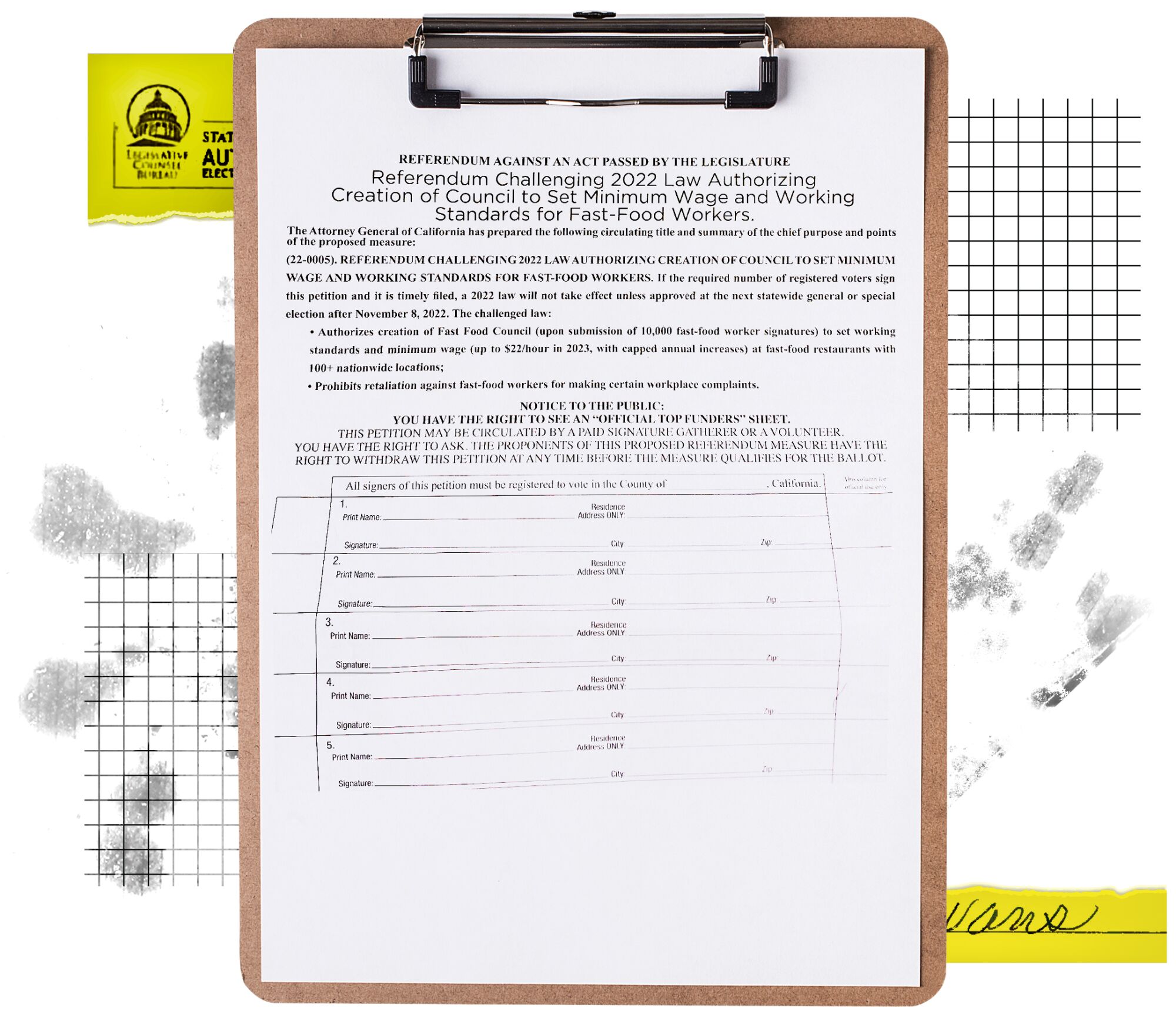

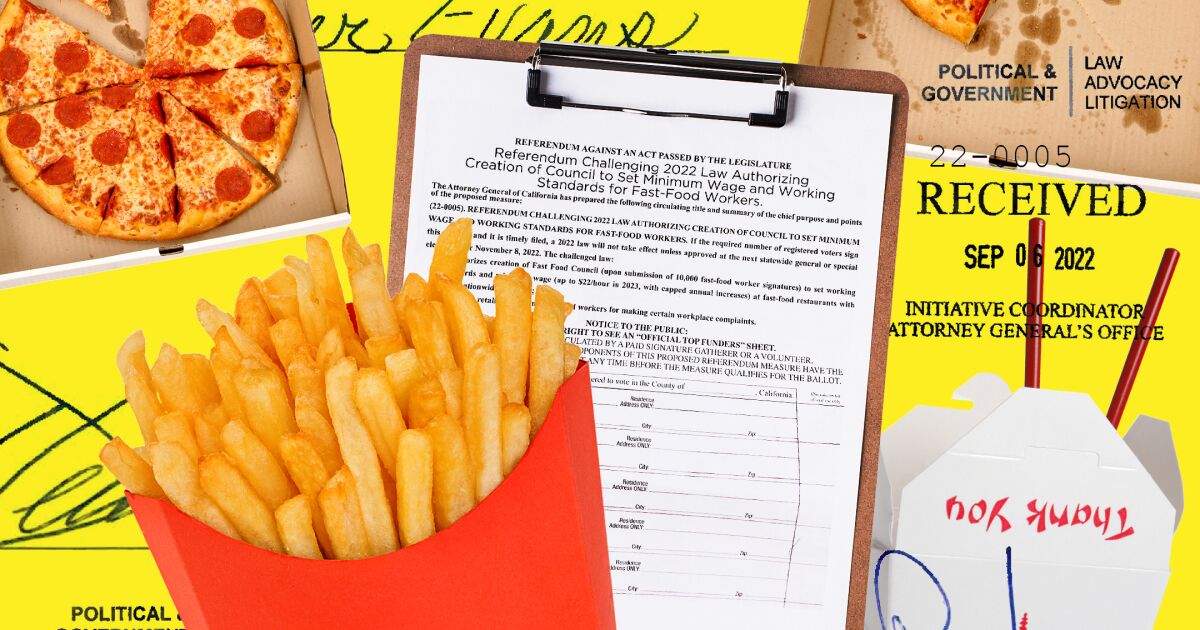

An image of petition signature sheet for a referendum opposing the creation of a statewide council to set wages and working standards for fast-food workers as outlined in California’s AB 257.

Although some people interviewed by The Times ultimately declined to sign the AB 257 referendum petition, seven voters realized they had signed in error. They include Lindsay Pérez Huber, a professor at Cal State Long Beach’s college of education, who signed a petition in front of a Ralphs in Westchester, and Rochelle Staab, 73, who signed at Cal State Northridge.

“I must have a sign on me that says ‘gullible,’” said Judy Carter, who signed the petition in front of a Marina del Rey Costco in October. Carter said she “will pretty much sign anything” she feels will ease the lives of people working minimum wage jobs.

The canvasser “really appealed to progressives. There are a lot of easy marks if you say, ‘Hey, do you support giving fast-food workers a fair wage?’ Well yeah, who’s going to say no?” Carter said.

UCLA sophomore Samuel Wolf, 19, said a signature gatherer who approached him on campus said the proposed referendum would raise wages for fast-food workers to $22 an hour. Wolf, who signed the petition, said he was dismayed to learn the referendum had qualified for the 2024 ballot.

“That just feels pretty depressing,” he said.

There is a short window to withdraw one’s signature from a petition. Voters must submit a written request for removal to an elections official in the county where they are registered before ballot measure proponents submit the signatures for verification. Voters would have had to submit removal requests by Dec. 5, the end of the 90-day period AB 257 referendum proponents had to collect signatures.

Bryan Culbertson, who said he was lied to by a circulator at the Oakland farmers market, said he found it difficult to find clear information online about how to withdraw his signature.

Of voters who told The Times that they mistakenly signed the AB 257 referendum petition, only Culbertson said he attempted to rescind his signature, and none filed notices to California’s election voter complaint portal. The California secretary of state’s office said a search turned up three naming AB 257 and 12 complaints mentioning “1137,” the oil well measure.

Although some people interviewed by The Times ultimately declined to sign the AB 257 referendum petition, seven voters realized they had signed in error.

Much of the behavior described to The Times appears to violate state election rules.

California’s election code makes it a crime for proponents of a proposed ballot measure and those whom they hire to engage in any tactic that “intentionally misrepresents or intentionally makes any false statement concerning the contents, purport or effect of the petition.”

The state also outlaws hiding or covering up the official summary of the measure from prospective signers. Election code violations can be prosecuted as misdemeanors.

Illich Covarrubias, 23, heard a circulator on campus parroting the pitch that signing the petition would help to raise wages for fast-food workers — except the campus was in Mexico. The circulator, a fellow student at the Technological Institute of Tijuana, was unconcerned whether the signers were California voters, Covarrubias said.

After some prodding, Covarrubias said, the circulator admitted he was falsifying California addresses; he had asked students to leave the address line blank.

“Obviously, I did not sign the petition,” he said.

A spokesperson for the International Franchise Assn., one of the groups spearheading the referendum campaign, pointed to safeguards built into the process.

The AB 257 referendum petition prominently displayed a neutral title and summary prepared by the California attorney general’s office, as legally required to reduce the risk that voters were misled when they signed the petition, she said. Random sample verification of signatures required by counties is designed to rule out invalid signatures, she said.

Political campaigns, the firms they hire to circulate petitions and the signature gatherers seldom face consequences for bad behavior.

The political firms hired by campaigns typically create shell companies, resulting in a confusing network of entities that makes regulatory oversight challenging.

For example, AB 257 referendum proponents hired a firm with the generic name 2022 Campaigns to manage marketing and signature collecting, campaign finance disclosures show. That firm shares an address with PCI Consultants, one of the biggest players in signature gathering.

PCI Consultants and other large firms typically contract with smaller vendors that specialize in various regions of California. The smaller vendors rely on local crew chiefs to recruit and supervise signature gatherers, many of whom travel from other states for the job.

The temporary workers earn more from some petitions than others. Canvassers averaged $16.18 a name for eight propositions on the 2022 California ballot, according to a Ballotpedia study.

No one from 2022 Campaigns or PCI Consultants returned calls from The Times requesting comment. Neither did the subcontractor vendors, including Bay Area Petitions, Florida Petition Management, On the Ground Inc., Carolyn Ostic, Pir Data Processing Inc., Your Choice, Schmitt Consulting Inc., and Valley Direct Marketing, according to public disclosures.

No formal registration, training or certification is required of individual circulators in California. By contrast, in Arizona, any person paid to circulate petitions for candidates, recalls or statewide initiatives and referendums must register with the secretary of state’s office.

UC Santa Cruz student Isaiah Berke said his interaction with a petition circulator got ugly in September after he objected to a canvasser saying that fast-food workers didn’t deserve wage increases. The circulator became enraged, got up close to Berke’s face and called him a homophobic slur dozens of times, according to a video of Berke’s comments about the incident during a UC Santa Cruz student government meeting.

“They were instantly very aggressive with me,” said Berke, who began to picket near the circulators regularly. “They were yelling at me a lot, when I was mostly explaining the law and its benefits to students.”

To help voters understand petitions presented to them, lawmakers in 2019 required that circulators make accessible a list of a measure’s top funders. But when UC Berkeley law student Bridgette Hanley asked to see the list, canvassers outside a San Francisco Target store didn’t seem to be aware of their obligation to show the list and didn’t show her a copy, she said.

California voters have the right to ask signature gatherers to show them a list of the three biggest donors behind the petition. The state publishes updated lists monthly. In November, In-N-Out Burger, Chipotle Mexican Grill and Starbucks topped the list of donors to the measure to overturn fast-food worker law, AB 257.

SB 1360, which went into effect this month, alerts voters of their right to view the top funders sheet before they sign by adding a line in every signature slot on petition sheets that reads “DO NOT SIGN UNLESS you have seen Official Top Funders sheet and its month is still valid.”

SEIU California held a video news conference in early December during which campaign finance transparency advocates called for additional reforms to California’s ballot initiative process. Discussion centered on adding a component that requires some demonstration of authentic grassroots support, for example, requiring that a portion of signatures be collected by unpaid volunteers.

Doing away with paid signature gatherers is largely off the table, given 1st Amendment protections that courts have broadly applied to political processes.

Dan Killam, 32, said “it was disturbing” to find out the petition he signed outside a San Francisco Target store in November would not help ease the burden of cash-strapped restaurant workers in the high-priced Bay Area.

It was even more upsetting, he said, to learn the AB 257 referendum petition had qualified for the 2024 ballot.

“It’s very against my values,” Killam said. “I got tricked, and I don’t like that feeling.”

“I’m a pretty politically active person. I read the news pretty obsessively. If I can be fooled, anyone can,” he said. “In the future I’m going to be reading the fine print.”

Times researcher Jennifer Arcand contributed to this report.

Discussion about this post