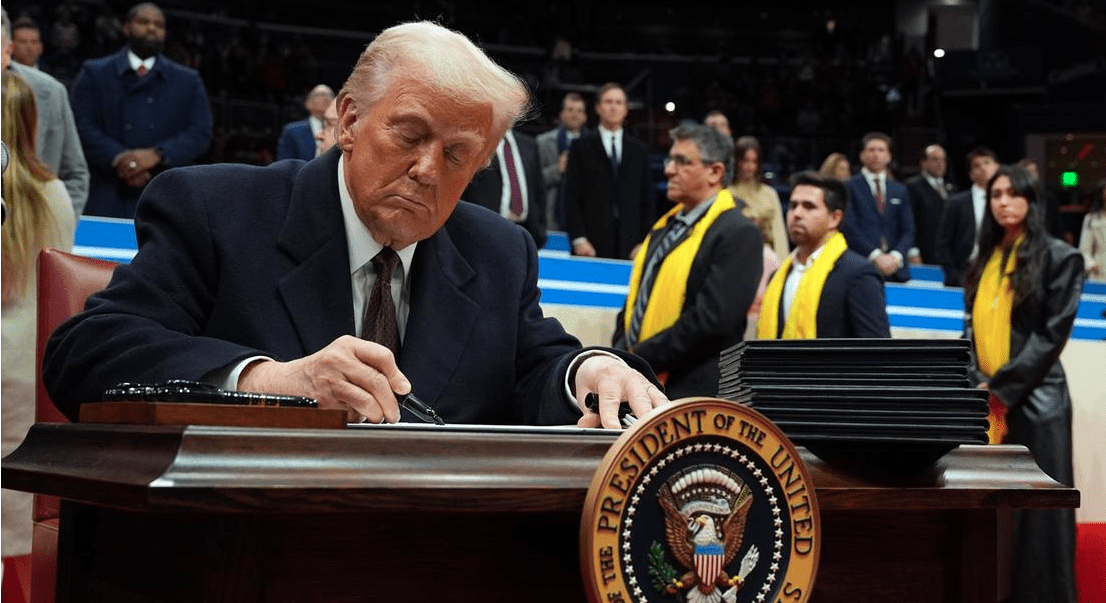

Health hazard: Dirty water streams though a street in Diepsloot, where the lack of formal sanitation systems are the prefect breeding ground for bacteria. Photo: Papi Morake/Gallo Images

In late March, three people who participated in a baptism ceremony in the part of the Jukskei River that runs through the Gauteng townships of Diepsloot and Alexandra, fell ill with a disease that residents in South Africa’s middle-class suburbs are mostly unfamiliar with.

Cholera causes a runny stool, and is spread when people drink water or eat food contaminated with a type of bacteria from the faeces of an infected person.

Whereas suburban houses are connected to sanitation systems that shunt sewage to formal water treatment plants, human waste flows freely in parts of Diepsloot and Alexandra.

“Sewage runs in the streets in Diepsloot, people sell food next to it, and cross over it every day,” says Brown Lekekela, a resident who works for the local women’s shelter, Green Door.

South Africa has had 10 confirmed cholera cases since February, including one death, and all have come from Gauteng’s townships.

Most people won’t fall seriously ill if they’re infected with cholera bacteria, but the germs can remain in their faeces for up to 10 days. In about one in 10 cases, however, the infection can cause serious symptoms such as watery diarrhoea, thirst and vomiting. If such a patient doesn’t get treated (for instance, with a special solution to replace the fluid and salts their body lost) they can die.

Experts at the National Institute for Communicable Diseases (NICD) worry that the poor infrastructure in townships such as Diepsloot and Alexandra open these areas up to large cholera outbreaks.

When people have to make use of pit latrines (as many in Diepsloot do) sewage can wash into the river system when it rains, says Juno Thomas, who heads the NICD team investigating the outbreak.

She says: “It’s when a major water source is contaminated that we [are likely] to see extremely large outbreaks.”

What causes a cholera outbreak?

This outbreak is South Africa’s first since 2008 and 2009, when the disease spread from Zimbabwe’s townships.

Back then, the NICD recorded 12 705 cases in South Africa, including 65 deaths.

Since that time, South Africa has had occasional cholera cases every few years, says Thomas, but these are usually imported when people travel home from areas where the disease is more common.

Those cases aren’t always a big problem because the disease mostly doesn’t spread beyond people who share a household with that traveller, says Thomas.

The first two confirmed cholera patients in South Africa this year were sisters who had travelled to a funeral in Malawi, where an outbreak of the disease has been raging since March 2022.

But, Thomas warns, the situation becomes more worrying when cholera cases pop up among people with no history of travel or any direct contact with those who have been out of the country. These are called indigenous cases, meaning people got the bug locally, for instance from a river.

Local infections are unusual in South Africa, but it appears to be what happened in the seven most recent cases — none of the patients had travelled or had any confirmed contact with people who recently returned from another country in our region.

Thomas thinks that contaminated river water is the most likely reason for at least three of those cases.

Why?

Because as part of the baptism ritual in the river, the man, woman and pastor drank copious amounts of river water before falling ill. They all fasted at the time, which means they couldn’t have become sick from sharing food.

The health department’s spokesperson, Foster Mohale, says people should avoid drinking or cooking with river or dam water unless it’s been boiled first.

People can also avoid becoming infected with the bacteria by washing their hands with soap before and after preparing food and after using the toilet, according to the United States Centres for Disease Control and Prevention.

Are there cholera vaccines?

People can get one of three oral vaccines, which all consist of two doses.

The two vaccines that are the easiest to roll out in emergencies are called Shanchol and Euvichol, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO), which says the two medicines are basically identical. A clinical trial published in The Lancet found that people who had been fully vaccinated with Shanchol were 65% less likely to get cholera than those who hadn’t received the drops five years after both doses of the vaccine had been administered.

The WHO recommends that people get vaccinated against cholera in places where there are often indigenous cases of the disease (such as Malawi and Bangladesh) or where humanitarian crises make cholera outbreaks more likely to happen (because water infrastructure may be destroyed or people could be forced to move to areas where there’s no sanitation system).

But because there are rarely indigenous cases in South Africa, the country’s routine childhood vaccination programme doesn’t include getting drops against cholera.

The WHO says that when countries are experiencing an outbreak (as South Africa is now) they should roll out vaccines as well, but global back-up stocks are running low because of an increase in cholera outbreaks in Africa, parts of the Middle East and India. These are being driven by conflict, floods and droughts, which reduce people’s access to clean water and force them to flee to neighbouring countries, where they sometimes spread the disease.

The shortage could be tackled in the coming years though since in November, the South African government-backed pharmaceutical company Biovac secured a deal to make an oral cholera vaccine from scratch for use both in Africa and elsewhere in the world.

Biovac says they expect their product to be registered by South Africa’s medicines regulator in 2026, following batches ready for clinical trials being expected from 2024. A South Korean nonprofit, the International Vaccine Institute (IVI), started “tech transfer” with the local manufacturer in January. That means the IVI will help Biovac with all the practical aspects of making the shot.

‘People have directed their sewers to the rivers’

Back in Alexandra, Thabo Mopasi wouldn’t be surprised if the Jukskei River is contaminated with cholera. He’s a resident in the township and runs a community forum on water and sanitation issues.

There, people have built makeshift drains that run directly from their toilets into the river, Mopasi says.

He explains: “There are also people who have built homes upstream from tributaries that run into the Jukskei. Those shacks have sewers that go straight into the streams.”

The bacteria that cause cholera is found in the faeces of infected people. So, if sewage runs into a river, the bacteria can spread to people who use the water.

If someone with cholera hasn’t washed their hands after relieving themselves, they could also pass the bacteria on when preparing food for others. Vegetables can even get contaminated when sewage containing the bacteria runs through soil where they grow.

Little can be done to solve the problem of sanitation in townships without providing people with formal housing that is connected to the sewage system, Mopasi says.

“The national government needs to take responsibility to house people, instead of leaving them to erect shacks on tributaries. We can clean the river, but tomorrow you’ll have to come back and clean it again.”

The department of human settlements, water and sanitation did not respond to Bhekisisa’s requests for comment.

This story was produced by the Bhekisisa Centre for Health Journalism. Sign up for the newsletter.

Discussion about this post