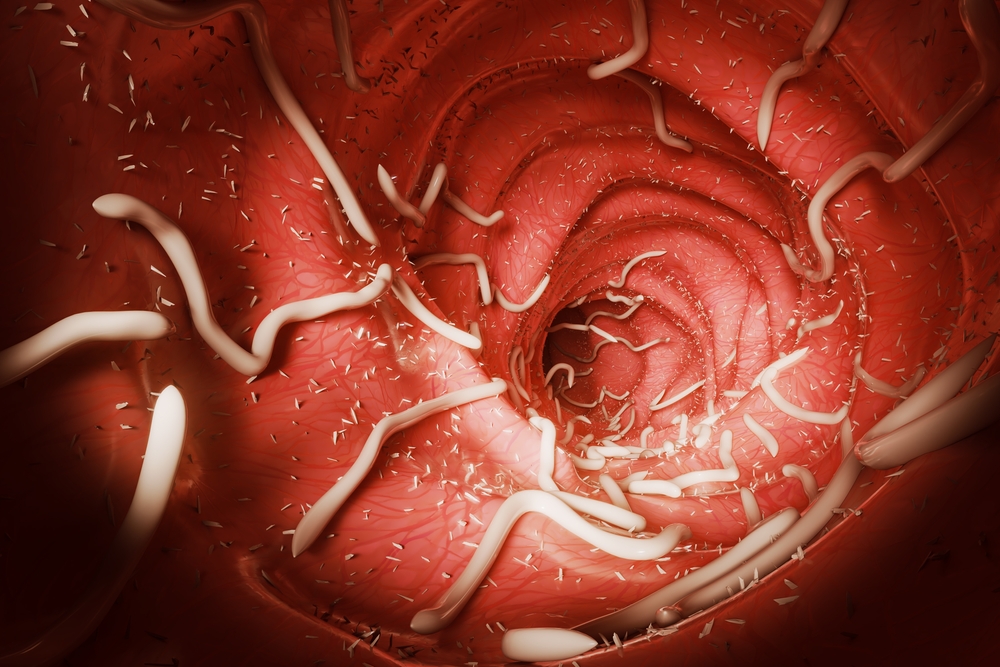

Worms wriggling around in your brain — it’s a particularly gruesome image that sounds like it came straight from a B horror movie. But several parasites can and do infect the central nervous system. The most common of these is Taenia solium, aka the pork tapeworm.

Gross as it sounds, infection with a pork tapeworm usually doesn’t cause much harm. Tapeworms get into the intestines when people eat undercooked pork that is contaminated with the larvae of the tapeworm. While in the intestinal tract, the larvae continue to develop, explains Astra Bryant, neuroscientist and parasitologist at the University of Washington in Seattle.

Getting Tapeworms in the Brain

You might think the adult worms would be more dangerous, but it’s actually the larvae that cause the most trouble. The adult worms lay eggs, and then the larvae migrate to other parts of the body. The liver and lungs are common destinations, but the larvae rarely cause any symptoms in these organs. However, if the larvae set up camp in the brain, they can cause serious health problems.

Once in the brain, they develop into cysts, a disease called cysticercosis. Cysticercosis is known to cause seizures, chronic headaches, and sudden-onset epilepsy. In fact, Bryant says, cysticercosis is one of the most common causes of acquired epilepsy.

If a tapeworm is in your intestine and not causing any trouble, you probably won’t know it’s there. When people do discover the infection, it’s usually because they see segments of the worm in their feces. Pieces of tapeworm are hard to miss because (and this is really gross) they wiggle around in the poop.

Read More: Hidden Epidemic: Tapeworms Living Inside People’s Brains

How to Treat Pork Tapeworm

When the worm is in the intestines, anti-parasitic medications can get rid of it. Once cysticercosis has developed, treatment becomes more difficult. If you kill the parasite with drugs, the death and resulting rupture of the cyst can trigger a dangerous inflammatory response in the brain, explains Bryant. When this happens, corticosteroids are used to try to keep the inflammation in check while the cyst is dying.

Once you know how much trouble T. solium can cause and how difficult it is to deal with if it makes it to the brain, prevention seems like a great idea. And that’s easy. Bryant advises practicing excellent hygiene and never eating undercooked pork.

Read More: Naegleria fowleri: The Brain-Eating Amoeba

Are All Brain Parasites Dangerous?

Odd as it sounds, brain parasites might be useful. Or at least one of them might be.

Toxoplamsa gondii is, as parasites go, pretty famous. It’s found in cat poop, and when it infects rodents, it has the bizarre effect of making the little critters lose their fear of cats, or of any predator for that matter. When it infects humans, the parasite can cause serious trouble, especially for immunocompromised people and infants born to newly infected mothers.

Most of the time, however, T. gondii doesn’t harm people. In fact, it lies dormant in more than a third of the world’s population. An international team of researchers led by scientists at the University of Glasgow and Tel Aviv University are working on a way to make T. gondii earn its keep.

Scientists have discovered how to use the parasite’s ability to cross the blood-brain barrier to deliver a therapy for Rett syndrome, a neurodevelopmental disorder that causes severe symptoms, including seizures, loss of speech, loss of muscle tone, and difficulty breathing. Potentially, the technique could be used to treat other neurological diseases.

Of course, to make this feasible, the researchers will have to make sure the therapy is safe. But the technique is promising.

“Evolution already ‘invented’ organisms that can manipulate our brains,” Oded Rechavi, one of the authors of the study, said in a statement announcing the research. “Instead of re-inventing the wheel, we could learn from them and use their abilities.”

Read More: The Biggest Parasite Can Grow up to 30 Feet Long, and Live in Your Stomach

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article:

Avery Hurt is a freelance science journalist. In addition to writing for Discover, she writes regularly for a variety of outlets, both print and online, including National Geographic, Science News Explores, Medscape, and WebMD. She’s the author of “Bullet With Your Name on It: What You Will Probably Die From and What You Can Do About It,” Clerisy Press 2007, as well as several books for young readers. Avery got her start in journalism while attending university, writing for the school newspaper and editing the student non-fiction magazine. Though she writes about all areas of science, she is particularly interested in neuroscience, the science of consciousness, and AI–interests she developed while earning a degree in philosophy.

Discussion about this post