Today, astronomers and space lovers around the world are collectively marveling at our mercurial presence in the universe, particularly as we drift the cosmos amid large asteroids like the one that wiped out the dinosaurs 66 million years ago.

June 30 marks Asteroid Day, a holiday observed annually to reflect on the prospect of a planet-destroying space rock striking Earth and what scientists are doing to mitigate that risk.

The day is observed on the anniversary of the 1908 Tunguska event in Russia, when a space rock about half the size of a football field broke up in the air over a remote forest in Siberia — the biggest asteroid strike ever witnessed on Earth. With a flash brighter than the sun, followed by a thunder-like noise, the fireball killed herds of reindeer, knocked people who were over 40 miles away (64 kilometers) from the impact off their porches and leveled about 80 million trees. The impact dumped so much dust in the air that sunsets were fiery red for days, and people who lived as far away as Asia could read newspapers outdoors until midnight.

More recently, in February 2013, a 20-meter (66-foot) space rock struck Earth near the Chelyabinsk city in Russia, injuring about 1,500 people and shattering over 3,000 windows in apartments and commercial buildings. The shockwave generated by the impact was so strong it circled our planet twice, scientists say.

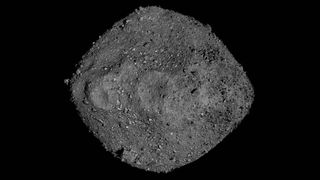

Related: Phosphate in NASA’s OSIRIS-REx asteroid sample suggests space rock Bennu hails from an ocean world

Although such devastating space rocks land more often in oceans than they do on land, the 2013 asteroid strike, just a decade ago now, “reminded us that these things do happen,” Nick Moskovitz of the Lowell Observatory in Arizona told Space.com. “Asteroids have this strange duality to them in that they probably delivered the ingredients for life to the Earth, but at the same time the wrong impact in the right place could lead to significant damage for whomever may be around.”

Asteroid Day is a global awareness campaign spearheaded by the Asteroid Foundation in Luxembourg, and it has been an official day in the United Nations’ calendar since December of 2016. In previous years, the day has been celebrated by dozens of local events in institutions around the world, with talks centering around asteroid science that were topical that year.

Last year, for instance, many events focused on NASA’s wildly successful DART mission, which smashed a refrigerator-sized spacecraft into an asteroid named Dimorphos and nudged the space rock off its orbit by 33 minutes, very likely changing the object’s shape as well. DART was humanity’s first planetary defense test, and proved scientists had the technology necessary to defend Earth if a similar space rock were to ever be on a collision course with our planet. “Last year, Asteroid Day was very much like DART fest,” said Moskovitz. “It’s a fun day.”

This year’s celebration, happening in around 30 institutions worldwide, including those in India, Africa, Europe and Mexico, includes talks about the European Hera mission, which is a follow-up to DART scheduled to launch in October that’s designed to assess the aftermath of the mission. On Friday and Saturday (June 28 and June 29) in Luxembourg, where the Asteroid Foundation is based, events ranged from seminars on asteroid science and space sustainability to workshops where visitors could build spaceships with Legos. At night, attendees explored the night sky real-time by virtually controlling telescopes in Tuscany, Italy, under the guidance of astronomer Gianluca Masi, who manages the Virtual Telescope Project.

Here’s a map outlining locations of similar ongoing events around the world. If none are nearby, you can tune into online discussions about asteroids by astronauts and industry experts that the foundation recently broadcasted.

In the U.S., hundreds of people are expected to join scientists today (June 30) for full-rim tours of the Meteor Crater, where asteroid science demonstrations and themed games have been planned along with food and drinks.

“Right here in northern Arizona, we can see the literal impact of asteroids on our planet,” Matt Kent, the president and CEO of Meteor Crater and the Barringer Space Museum, said in a previous announcement. “What better place to hold an Asteroid Day event than here?”

By 7:00 p.m. local time, visitors will begin heading to the Lowell Observatory, which is about a half hour drive away, for telescope viewing and science presentations given by astronomers, including Moskovitz. Because Asteroid Day falls on a weekend this year, “we could see pretty big crowds between the two sites,” he said.

At Lowell, research scientist Brian Skiff will discuss the odd quasi-moon of Venus. Also considered a near-Earth asteroid, the space rock was discovered in 2002 and recently received the snappy name Zoozve. It seems to circle Venus but is not permanently tied to the planet’s gravitational tides, meaning it will eventually be kicked away. It’s considered a potentially hazardous space rock, but is not on a collision course to Earth.

Also at Lowell, Moskovitz will present a project that uses off-the-shelf security cameras to snap pictures of the night sky in search of meteors, managing to catalog up to 500 each night. The project, called LO-CAMS (short for Lowell Observatory Cameras for All-Sky Meteor Surveillance), “is all about cheap hardware put to good scientific use,” he said. “The night sky can be very active if you have the right instruments watching.”

The project began as a hobby project eight years ago by Moskovitz and has since grown into a full-blown operation with dozens of cameras on the roofs of science institutions, schools, colleges and, at times, even private residences across Arizona. From the HD-resolution photographs these cameras capture, Moskovitz and the LO-CAMS team can predict the paths of pea-size meteors and later search for pieces that may have survived their journey to the ground, “like an ultimate scavenger hunt,” said Moskovitz.

In an intriguing cosmic coincidence, this year’s Asteroid Day comes at the heels of two asteroids that just brushed past Earth. Neither was on a path to impact our planet, to be clear, but the rendezvous was notable nonetheless. The larger of the pair, a Mount Everest-size space rock named 415029 (2011 UL21), whizzed past our planet on Thursday (June 27), flying about 17 times farther from Earth than where the moon sits, on average. However, the smaller asteroid, dubbed 2024 MK, hurtled within the moon’s orbit of Earth on Saturday (June 29), close enough to be seen by stargazers using small telescopes in dark sky locations.

If an asteroid were ever to be on a collision course with Earth, asteroid-deflecting missions like DART would be crucial to mitigate the risk of an impact. The mission, which is universally viewed as a success on many levels, is a testament to our current technology and the team of over hundred scientists and engineers who developed it. The efficiency of any strategy, however, really comes down to the size of the space rock and how much lead time we get. The only way to reduce the risk of a sudden asteroid strike is to find and track as many asteroids as we can, because the ones that pose a risk to Earth are “typically objects discovered now with potential impacts decades or centuries in the future,” said Moskovitz.

Technological advancements in recent years have allowed scientists to catalog an increasing number of asteroids in our solar system, including artificial intelligence software that has revealed over 27,000 asteroids previously overlooked in telescope images. At least a couple million more space rocks are expected to be discovered by the upcoming Vera C. Rubin Observatory, which, starting next year, will image the southern sky every night for at least a decade. At such a cadence, the observatory is expected to double the number of known asteroids in just its first six months of operations.

Within the next few decades, scientists may be able to mitigate — if not largely extinguish — the risk associated with large asteroid impacts, said Moskovitz.

“That’s a luxury the dinosaurs didn’t have, and it’s something that will forever benefit us moving forward as a species.”

Discussion about this post