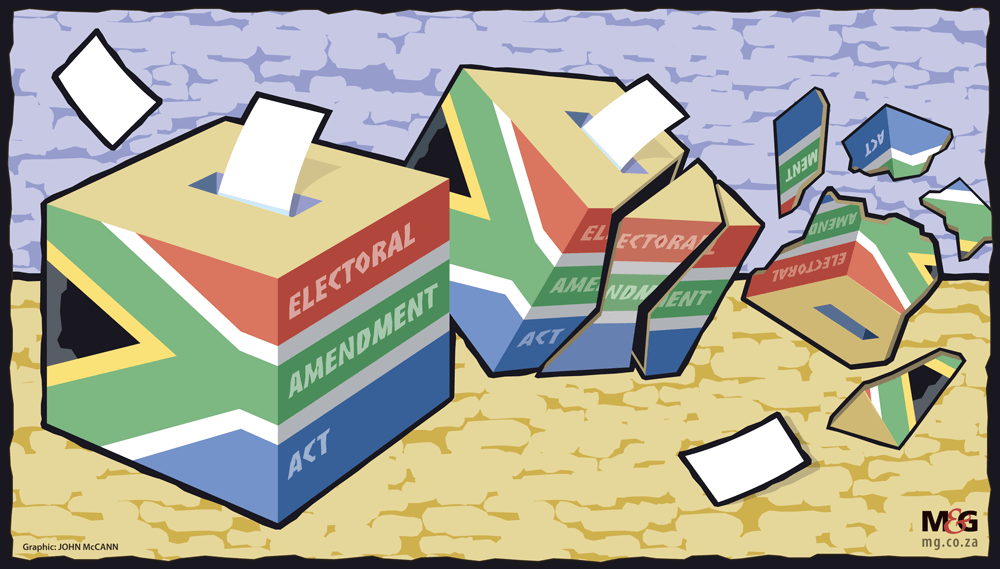

(John McCann/M&G)

When the number of parties potentially contesting the national and provincial elections started to head into the hundreds, it seemed as if we were headed for a DStv election: hundreds of channels and nothing to see. But, after the successful constitutional court challenge to the requirement of a huge number of signatures for independent candidates cut that to 1 000 signatures, the possibility shifted to a ballot the size of a telephone directory.

While the target shifted for independents, parties not represented in parliament still have to obtain signatures adding up to 15% of the quota for one MP in every province where they want to contest, for national and provincial elections.

This signature requirement was originally intended to thwart huge numbers of independents from running; cutting the requirement for independents to 1 000 signatures undoes that.

But it is much more onerous for national campaigns because an independent runs in a region (effectively a province, but renamed, as it is a ballot for the national parliament, not the provincial assembly). Parties not yet represented in parliament have to obtain the number of signatures required in every region; if they miss any, they miss the opportunity of votes on a regional ballot.

This matters because the national vote is split equally between a single national ballot and a regional ballot per province.

The total number of signatures required is not easy to find; it was about 107 000 to contest all regions, and signatures were also required to contest provincial legislatures when I first checked but now I see reports that the number is “only” 60 000.

A practical issue for gathering signatures is that only registered voters’ signatures count.

Any party capturing signatures not only has the enormous task of doing so, but may have to go out searching for more signatures when some turn out to be invalid.

To put these numbers into context, the eight smallest parties currently in parliament got there with less than 100 000 votes and four of those parties scored fewer than 60 000 votes. None of them face this signature requirement to run again.

A possibly unintended consequence is that parties that are not strongly organised have been eliminated. While this is undemocratic and unfair in that disorganised parties already in parliament do not have this hurdle, it has another unintended consequence.

The new parties still in the fray have had to start early with getting their ground game organised. It is a misconception that poll outcomes largely rest on rallies, speeches, TV coverage and policies. A strong ground game matters.

For this reason, the registration process could result in some surprises. It’s worth watching the new players, as well as those not previously successful at national level who have managed to meet the signature requirements in all or at least most regions. Examples include Forum 4 Service Delivery, which was previously only successful at municipal level, and Rise Mzansi.

A bigger issue that really calls for electoral reform is the incompatibility between a closed proportional representation (or PR) list and independent candidates. A closed list takes the choice of candidates away from voters; the party decides on the order. On the other hand, voting for an independent is a vote for a specific person.

To make matters worse, there is no mechanism for filling a seat vacated by an independent; it simply stays empty until the next election. If this happens with one or two independents it’s no big deal. But what if a substantial fraction of the parliament is independents and they all vacate their seats, for whatever reason? That could shift the balance of power in a parliament without a clear majority.

A closed list is not inherently democratic because it distances decisions about representation from the voter. The 2018 amendments to the Political Party Funding Act regulate party funding but do not regulate internal campaigning, so there is no scrutiny of jockeying for positions and hence potential corruption of setting up a party PR list.

The CR17 campaign and that of Ramaphosa’s rivals to win control of the ANC fell outside the Act, and there is no legal requirement for any of this to be transparent.

Another big issue is that there is a huge imbalance between the accountability of an independent MP and a party MP. No one can remove an independent MP once elected, except through parliamentary processes to deal with misconduct.

A political party can strip a member of membership (provided it is a proper process, not overturned in the courts). While a trusted independent who works for their constituency can be superior to a party MP who works for their party, there is no way to recall an independent who doesn’t perform.

In short, the Electoral Amendment Act is severely broken and we need substantial electoral reform. My proposal is to turn a constituency system into an open list PR election. The approach is to divide the country into 400 constituencies, one per MP. All candidates, whether party or independent, nominate in a constituency.

Once votes are in, the number of seats per party and for independents as a group is calculated. Then each party’s candidates are ranked from highest to lowest number of votes, which gives you an open party list. For independents, they are put on a single list and the number elected and their ranking is calculated the same way.

There are three benefits to doing it this way. The power of internal party processes, which can easily be corrupted, is reduced. Voters have an MP they can relate to and call to account. And vacating a seat can result in a by-election, because it is clear where the departed MP’s votes came from.

An additional point that can be considered is whether a party should still have sole power over removing an MP (unless they are guilty of misconduct). A recall mechanism by petition from their constituency could also apply to independents. But such a mechanism must be designed with care to avoid abuse by political opponents.

The Makana Citizens Front proposed a mechanism where 100 voters could petition to remove a non-performing councillor but the petition had to be well motivated, and the councillor would have had the opportunity to answer the charges.

The mechanism for removing an MP would have to be robust to avoid abuse.

This system may result in some constituencies electing more than one MP and others none; it would be in the interests of MPs elected in neighbouring constituencies to work in those with no MP to secure future votes.

Whether this is the best idea is not my point. We need new ideas. The current system is broken.

Philip Machanick is an emeritus associate professor of computer science at Rhodes University.

;Resize=(1180))

Discussion about this post