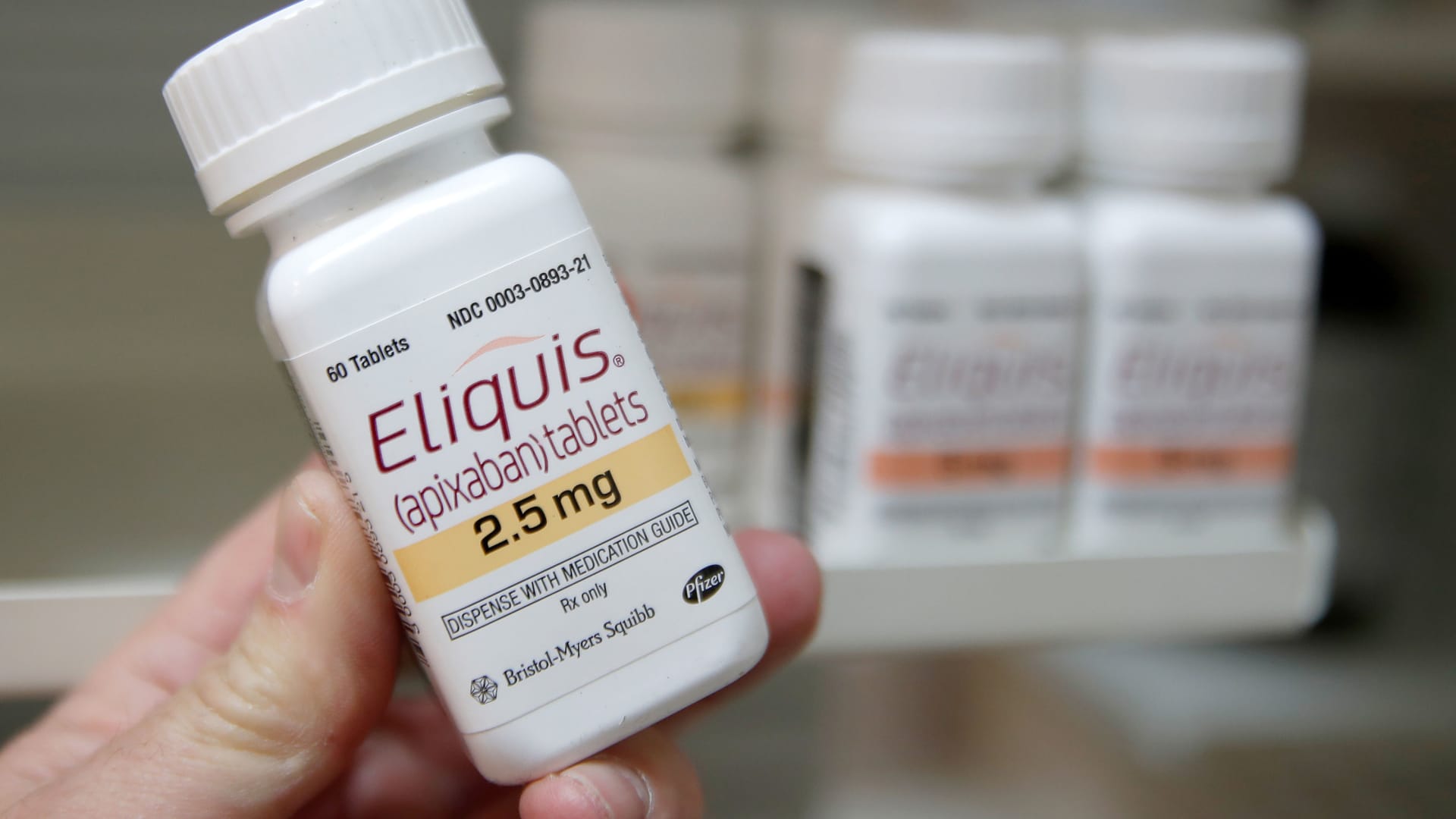

A pharmacist holds a bottle of the drug Eliquis, made by Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, at a pharmacy in Provo, Utah, January 9, 2020.

George Frey | Reuters

A federal judge on Friday declined to block the Biden administration from implementing Medicare drug price negotiations, upholding for now a controversial process that aims to make costly medications more affordable for older Americans.

Judge Michael Newman of the Southern District of Ohio issued a ruling denying a preliminary injunction sought by the Chamber of Commerce, one of the largest lobbying groups in the country, which aimed to block the price talks before Oct. 1.

That date is the deadline for manufacturers of the first 10 drugs selected for negotiations to agree to participate in the talks.

But Newman, a nominee of former president Donald Trump, also declined to grant the Biden administration’s motion to dismiss the case entirely.

Instead, he asked the Chamber to amend its complaint by Oct. 13 to clarify certain details in the case.

Newman also gave the Biden administration until Oct. 27 to renew its motion to dismiss the case.

He said “a final determination on standing issues will be made following a short (60-day) discovery period and—assuming they are filed—renewed motions to dismiss.”

The ruling from Newman is a blow to the pharmaceutical industry, which views the process as a threat to its revenue growth, profits and drug innovation.

President Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act, which passed in a party-line vote last year, gave Medicare the power to directly hash out drug prices with manufacturers for the first time in the federal program’s nearly 60-year history

The Chamber, which represents some companies in the industry, and drugmakers like Merck and Johnson & Johnson filed at least eight separate lawsuits in recent months seeking to declare the negotiations unconstitutional. But the Chamber’s suit was the only one seeking a preliminary injunction.

Michael Newman, U.S. District Court Judge Ohio

Source: U.S. District Court

The Chamber’s lawsuit argues that the program violates drugmakers’ due process rights under the Fifth Amendment by giving the government the power to effectively dictate prices for their medicines.

The Chamber said an appeals court established a precedent that when the government sets prices, it must provide procedural safeguards to ensure a company receives a reasonable rate and fair return on investment. It stems from the 2001 case Michigan Bell Telephone Co. v. Engler, according to the Chamber.

The Medicare negotiations do not provide these safeguards and impose price caps that are well below a drug’s market value, the Chamber argued.

“There is a very, very high risk, maybe a guarantee, but certainly a very, very high risk, that this regime will result in prices that are unfair,” Jeffrey Bucholtz, an attorney for the Chamber, told judge Newman during a hearing earlier this month.

He added that drugmakers either must agree to the price the government sets, or face an excise tax of up to 1,900% of U.S. sales of the drug.

But lawyers for the DOJ said during the hearing that the program was far from compulsory. Drugmakers can choose the alternative to those two options: Withdraw their voluntary participation in the Medicare and Medicaid programs, according to attorney Brian Netter.

“The measure of relief here is for manufacturers to decide whether they want to stay in the program under the terms that are on offer,” Netter said. “If they choose not to, that’s their prerogative.”

The other suits are scattered in federal courts around the U.S.

Legal experts say the pharmaceutical industry hopes to obtain conflicting rulings from federal appellate courts, which could fast-track the issue to the Supreme Court.

Medicare covers roughly 66 million people in the U.S., according to health policy research organization KFF. The drug price talks are expected to save the insurance program an estimated $98.5 billion over a decade, the Congressional Budget Office said.

In August, the Biden administration unveiled the 10 drugs that will be subject to the first round of price talks, officially kicking off a lengthy negotiation process that will end in August 2024. The reduced prices for those initial medications won’t go into effect until January 2026.

That includes blood thinners from Bristol-Myers Squibb and J&J, and diabetes drugs from Merck and AstraZeneca. It also includes a blood cancer drug from AbbVie, one of the companies represented by the Chamber of Commerce.

Discussion about this post