An essay by Lily Duval from the just-released anthology Otherhood: Essays on being childless, childfree and child adjacent.

I was 22 when my friend Alice gave birth in the living room of our pokey Addington flat. She laboured in the blow-up pool for hours. Garish fish swam along the inflated plastic sides as she breathed and pushed, breathed and pushed. We (her partner, our other housemate, Clara, and I) wrung out hot towels to put on her lower back. We took photos and stoked the fire. I was wowed by how contained she was, her pain threshold honed from years of kidney stones. She made birth look powerful and strong.

Still, it was a lot. A beautiful, mind-bending, life-altering lot.

Homebirth and child-rearing were the unexpected backdrop to the first half of my 20s. While other people I knew were experimenting with whatever substance was on hand or starting serious careers, I was bouncing babies or building block towers. This wasn’t by design. I needed somewhere to live after my flat dissolved and a friend of a friend knew two women who needed a flatmate. One of them, Clara, had a one-year-old baby.

Alice and Clara were already friends, but I slipped easily into their world in the way you do when you’re young. We bonded over books, crafts and a collective belief that the nuclear family was nuclear. Our partners lived elsewhere — including the father of the child. We wanted to create a women’s space.

Living with a baby turned out to be fun. I also discovered I was quite good with them. I could hold them confidently, sling them from hip to hip as I popped the kettle on or checked the mail. I could calm them down or entertain them with nonsense noises. This was a mutually beneficial arrangement. When I was on the floor drawing with crayons or reading stories, I forgot myself. The depression and anxiety that had dogged me since childhood dimmed. Compared to the hot mess of university parties, life with a child felt wholesome and meaningful.

As much as I enjoyed this new life, having my own babies was not on my mind. Children seemed like something for later – something that was situationally dependent. Children, I thought, were to be considered if the right person came along. I was good at considering things – I’d racked up four years of student debt doing it.

I was still young enough to find new and unusual things exciting. And living with children in my early 20s fit the bill. In our society, you don’t usually live with babies unless they’re related to you in some way. The house was a unique opportunity to experience life with children without the weight of a lifelong commitment.

It wasn’t only the baby that made our house different. Nothing we did was subtle or coincidental. Everything from the décor to the food we ate was carefully planned. We idolised women’s communes from the 1970s and radical activists like those who occupied Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp. We plastered the living room walls with feminist icons and our shelves were stacked with books by Anaïs Nin, bell hooks and Virginia Woolf. One day, at a secondhand store, I found a book called Lesbian Nuns Tell Their Story, and proudly sat it alongside The Enchanted Broccoli Forest and Cunt: A Declaration of Independence. Our house was a cauldron of religious-flavoured idol worship and raging wannabe-lesbian separatism. Even our letterbox wanted to “Smash the Patriarchy”.

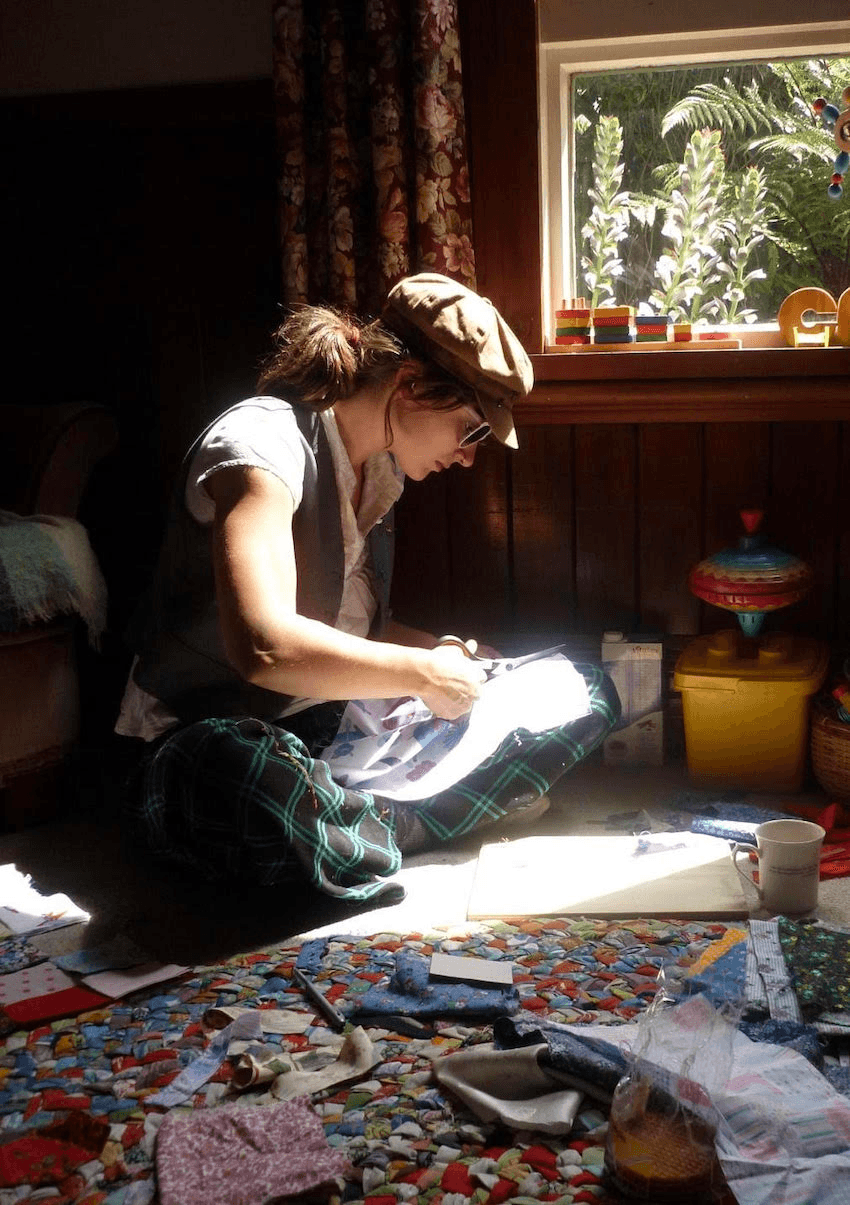

The house was our collective creative womb. We sewed, crocheted, knitted, painted, scrapbooked and cooked. We blended the aesthetics and skills of storybook grandmothers with radical feminist ideology. We were militantly vegan. We hosted “Food not Bombs”-style community meals in the park, where we foisted baking made from chickpea flour and tofu on unsuspecting neighbours.

Each of us, at different times, shaved our heads. Even though I’d sported a short and shaggy style since high school, the experience of buzzing my hair to a thin layer of fuzz was more intense than I was willing to admit. I felt a sense of loss, as if my hair had sheltered me from the hard realities of the world. With my hair went my grandma’s floral dresses and unwanted attention from men. I started a lifelong love affair with overalls and checked shirts.

Bit by bit, we turned the back lawn into a riotous vege garden. We lined the kitchen window sills with used soy milk cartons made into seedling trays. That first summer, sunflowers arched overhead and sweetpeas, borage and nasturtium tumbled from curving brick-bordered beds. We planted the “three sisters” – corn, beans and pumpkin – and saw ourselves in them: the corn tall, straight and supportive to give the beans something to climb, while the pumpkins provided shade for the roots. Out back, a ring of stones marked a pagan circle where our women’s group concocted a pastiche of rituals celebrating female goddesses and the seasons.

All this wild creative energy manifested in other ways. By the second summer, Alice was pregnant. I remember taking her picture in the third trimester of her pregnancy; she held her belly while the garden rampaged around her, swollen pumpkins at her feet.

This seemed like a natural trajectory. What was more organic and women-centric than giving birth and nurturing a child? I wasn’t about to get pregnant, but I found ways to contribute my thoughts, writing an honours essay about Margaret Atwood’s Oryx and Crake and male jealousy of the power of birth.

In our house, birth was more than a remarkable physical triumph of the female body, it was deeply symbolic. Clara had taken the high she experienced giving birth at home and channelled it into studying midwifery. We spent many evenings discussing how homebirth could give women power over their own bodies. Clara had her birth picture up on the lounge wall. In the photo, she cradled her first child, her henna-ed hair flaming against the redness of labour. Anyone who came over for a cup of tea could see the bloody naked triumph of her motherhood.

Life was electrically ideological. It was also hypocritical.

After Alice’s baby was born in the living room, the energy in the house changed. Rather than three women to one child, there were two children to contend with. And from my vantage point, newborns seemed impossibly hard. Baby cries percolated in the night, occasionally bubbling over into long screams. Morning brought little reprieve. As well as the breastfeeding, there were buckets of soiled nappies to scrub and washing to hang out. Mothering looked beautiful but also chaotic and stifling. I had no idea how Clara and Alice were coping. I think often they weren’t.

Tensions had always simmered beneath the sisterhood, but with two babies in the house, they started to escalate. From Clara, I endured comment after comment about my childfree privilege – jealousy over my ability to pick up or put down a baby depending on my mood. I was given the silent treatment one day and then asked to babysit the next. I was always both inside and outside family life. For all the help I tried to offer, I couldn’t make milk flow from my breasts.

At times, I thought about bowing out. But if I felt as if I wasn’t ready for this life, how did Alice and Clara feel? I felt compelled to stay and help, and I watched as motherhood swallowed them.

There was the mundanity of rent, food and bills, and external pressures, too. As hard as we tried to fortify the world we’d built, the outside world insisted on ignoring the letterbox. There were the frowns of disapproval from my housemate’s parents at the way the children were dressed (boys in dresses!) or the strange separate living arrangements with the fathers. And there were the men themselves.

On paper, there was never much space for men in our world, but the children of the house told a different story. Men had always lurked on the periphery. I think we were ashamed of them. Mine snuck in my sash window at night. They were the quiet click of the front door at bedtime, the odour change in the “if it’s yellow let it mellow” toilet. They were like good Victorian children or obedient ghosts.

By the time Alice’s baby was born I’d ditched cis men for queer partners, but parenthood tied Alice and Clara to the fathers of their children. The difficulty of ferrying small babies between households eventually wore down any separatist fantasies we’d nurtured. Men started to come through the doors, in the daylight.

Clara gave birth to her second child in her bedroom, behind a closed door. Only her partner and the midwife were in the room with her. Before the baby arrived, I’d shifted into the garden shed, where bamboo forced its way through the floorboards and strange moulds crept along the walls. It was a high price to pay for a sense of independence. I wasn’t the only one not coping. Soon, overwhelmed by expectation and the relentlessness of living up to our own self-imposed doctrine, Alice moved out to live with her partner and some other friends. When the earthquakes shook the feminist icons off the living room wall, I decided I’d had enough, too.

Our vision lasted no more than a few years, but I still find tendrils of that experience curled around my adult self. The years I spent in that flat were formative – I became a feminist, learnt to cook and garden and craft, and I learnt a lot about children. But they were also damaging to my self-esteem.

It took me a while to embrace my freedom. Eventually, I began to think that if it was a privilege to be childfree, then the opposite must also be true. Privately, I started to feel that if everyone could spend some of their early twenties living with children — and especially with babies — then far fewer people would decide to have them later on.

For the remainder of my 20s, being queer proved to be its own form of birth control. Still, my childfree state was never a conscious decision. I’ve never felt that certainty about not having children I’ve heard expressed by other women. For me, it was mostly down to circumstance. At 21, I’d wandered into a situation that proved to be more effective than a long-lasting IUD. And though my opinions might have softened by the time I hit 30, my chaotic romantic life made children look like a laughable fantasy. I felt the tentacles of my family’s depression and anxiety questing for the next generation. I didn’t want to create anything it could sucker onto.

When I started dating cis men again in my 30s, I realised I might need to firm up my position. And when I met my partner of the past five years, the topic came up pretty quickly. He’s older than me and has never wanted kids, so it was not up for debate. Although it felt like another situation I’d simply wandered into, I was happy to have some certainty.

Now that I know I won’t have children, I’ve fortified my childfree narrative. If I ever feel a pang for my future old-biddy self, I focus on all the time I have to go tramping, lie in bed in the mornings, and write a book.

I was 26 when I held my sister’s hand as she brought my niece into the world. She was at home in a birthing pool. Unlike Alice’s, this birth felt more like how mine might go if I was to have a baby – a frenzy of uncontained agony and joy.

It was another successful homebirth. My sister was powerful and strong and my niece emerged in the tumbledown living room of my sister’s Woolston house in the early hours of the morning. I held her as my sister showered, and she did her first poo on me. It was the perfect benediction for a new auntie.

Being present for the birth of a child is a real honour. I can see why people want to become midwives – how they become addicted to the electricity of birth. There’s something so good and hopeful about bearing witness to the beginning of new life.

But, however powerful birth is, I’ve come to put more stock in the next part. Because despite the madness of that Addington house there were some things we were right about. It’s important there are more people in a child’s life than their parent or parents, so with my free time I take my five nieces and nephews on adventures – foraging for fungi, playing dinosaurs or simply reading books before bed.

My childfree privilege is the privilege to be in their lives – not as a mum or a dad, but as an auntie.

‘The Addington house’ by Lily Duval is extracted from Otherhood: Essays on being childless, childfree and child adjacent edited by Alie Benge, Lil O’Brien and Kathryn Van Beek ($40, Massey University Press). Otherhood is available from Unity Books Wellington and Auckland.

Alie Benge, Lil O’Brien and Kathryn Van Beek will be appearing along with some of the book’s contributors at the Auckland Writers Festival 14 – 19 May. For more information and tickets visit www.writersfestival.co.nz

Discussion about this post